In the few hours remaining before the Japanese attack, American frontline troops were apprehensive about the possibility of such an assault, as was their commander, Brigadier General Martin. Despite this unease, there was no uniform stage of readiness among U.S. units covering the river; no reinforcements came from the MLR; no reserve moved east of the Nigia River to replace those troops used for the reconnaissance in force. Lt. Col. Edward Bloch's 3d Battalion, 127th Infantry, "certainly expected some action during the night." The 1st Squadron, 112th Cavalry, on his South flank, merely recorded a 7 July alert from the commander, Eastern Defense Command, about increased enemy activity near the north center of the Driniumor line. The 2d Battalion, 128th Infantry, believed that the Japanese would attack sometime between 1 and 15 July and that its sector would be the target.

Until 9 July, the 2d Battalion's sector had about a 1,600-meter frontage, with the 1st Battalion, 128th Infantry, and the 3d Battalion, 127th Infantry, covering its northern and southern flanks, respectively. When General Krueger, through Major General Hall, ordered the 1st Battalion to conduct a reconnaissance in force, 2d Battalion had to occupy the line vacated by the 1st Battalion. In order to accomplish this, the 2d Battalion committed its reserve, Company F, to hold the 1st Battalion's former line, about 2,700 meters long. Company E, with one heavy machine gun platoon attached, extended its north flank an additional 900 meters, which made the company responsible for a 1,600-meter defensive frontage, normally a battalion-size sector. Such extended frontages and the many small islands covered with dense foliage in the Driniumor made an adequate defense impossible.

Orders, though, were orders, so during the day of 10 July the men of Company E dug their individual fighting positions. The company commander, Capt. Thomas Bell, placed three or four men at those places he felt were most vulnerable, although everyone realized they were incapable of stopping a determined Japanese attack. The four-man fighting positions also allowed one man to stand guard while the three others slept at night; yet should the enemy attack, the men could disperse to their nearby fighting holes for the battle. On Company E's south was Company G, which occupied a front about 500 meters south along the river. There Capt. Ted Florey, Company G commander, had his men string a single strand of barbed wire from rock to rock all over the riverbed. It was little more than a trip wire, but it was all that he had available. On the night of 10 July, 2d Battalion found itself defending almost 4,500 meters of river line in jungle terrain without any reserves to plug a possible enemy breakthrough.

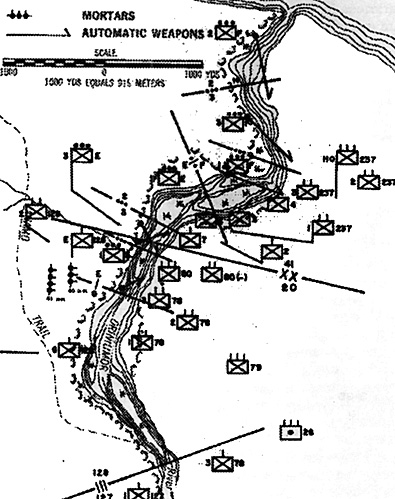

The Japanese also had problems. The 237th Infantry was to spearhead the attack across the Driniumor against Company E's sector. Col. Nara Masahiko, the regimental commander, echeloned his three battalions in column. On his left, the 80th Infantry, 20th Division, lined up for its assault.

On its left, the 78th Infantry had its 3d and 1st battalions on line along the riverbank. The 6th Company, 2d Battalion, 237th Infantry, and the 1st Mountain Artillery Battalion would create a diversion against Company F along the coast. The 26th Field Artillery Regiment would support the 78th and 80th regiments' offensive.

But the plan was already unraveling. The 237th Infantry did not reach the Driniumor until the afternoon of 10 July because of the delay in hand-carried orders reaching its parent 41 st Division. With the exception of the 237th's 1st Battalion, no other Japanese had even seen in daylight the ground that they had to attack over in darkness in just a few hours. Although there were guides and trail markers to lead them to their assembly areas, moving forward after nightfall further confused soldiers unfamiliar with the terrain. Moreover, the Japanese would launch their attack believing that they faced three U.S. infantry battalions. Only later did they learn that their previous reconnaissance had missed the arrival of the 112th Cavalry, and consequently, they could not know that the Americans had shortened and strengthened their line. The attack plan had also been revised. According to the original plan, the Japanese attack would begin at 2200, about thirty minutes after moonrise, but this was changed to provide for a ten-minute artillery and mortar preparation to start at 2150 and to continue to the time of assault. Not all the Japanese units, however, received word of this important alteration.

As the American reconnaissance in force advanced along the U.S. northern and southern flanks, they moved past the assembly areas of six Japanese battalions, five infantry and one artillery. The reconnaissance in force, as well as American patrols operating on the east side of the Driniumor, also missed the arrival of the 237th Infantry Regiment during 10 July, although an "unknown number of Japanese soldiers" were reported two miles southwest of the mouth of the Driniumor, and the sergeant who sighted them felt that a strong Japanese attack was imminent. Opposite Company E's front, the Japanese were less than ninety meters from the Driniumor's east bank.

Along this sector, the width of the Driniumor riverbed varied between 70 and 120 meters, with a meandering stream 30 to 50 meters wide. The water was waist deep with a slow current. The stream bed was rocky and shallow in normal weather, but the banks were steep; the west bank (the American side) was about one to two meters high. Reeds or canebreaks grew to the height of a man's head and extended forty-five meters inland from either bank. These were major obstacles to men whose strength had so greatly deteriorated during their march to the Driniumor. Maj. Yamashita Shigemichi, commander, 1st Battalion, 237th Infantry, was about to lead the advance elements of these units across the Driniumor. He later recalled that, at the time, he and his men were so hungry that they were thinking more about breaking into the American positions to seize American rations than they were about the possibility of being killed. Yet Yamashita realized the crossing might be a costly, difficult attack. The afternoon of 10 July he confessed his misgivings to his regimental commander. Colonel Nara simply told Yamashita, "It's an order. Let's get on with it."

Maj. Kawahigashi Moritoshi's 1st Battalion, 78th Infantry, would spearhead the 20th Division's attack. His battalion had about 400 effectives, one 70-mm battalion howitzer, and four heavy machine guns, making it the strongest of the 78th's battalions. Unlike the 237th Regiment's predicament, Kawahigashi enjoyed detailed reconnaissance information about the terrain he was about to fight on. It was, however, too much to ask the exhausted, nearly spent troops who subsisted on short rations during a two-month jungle march to conduct a silent night attack. The attackers had left their assembly area and even crossed the river in comparative silence, but the cumulative fatigue finally overwhelmed them. Along the east bank, the weary troops could not climb up the two- or threefoot bank without excessive slipping, sliding, and banging of equipment. Muffled threats and curses to keep quiet did no good. Their limit had been reached, and they could do no more.

Several men of Companies E and G heard noises from across the river, but they remained crouched in their foxholes and passed no word of the sounds to their comrades. What these Americans heard was Major Kawahigashi's men moving across the Driniumor. Finally, an American defender from Company E or G fired, and then a hail of small arms and automatic weapons fire lashed the struggling Japanese soldiers. The volume of deadly fire stunned Kawahigashi's officers and men, who, based on previous reconnaissance reports, thought that they would need little firepower support to force the river.

Consequently, their battalion machine guns had not been sited for firing, because the battalion, like the division, like the army, had anticipated an easy crossing. The battalion's 70-mm gun had only two rounds of ammunition brought forward-in part, because Japanese artillery doctrine insisted on conserving ammunition with a one-round-one-hit philosophy. Under heavy fire, the men of the 1st Battalion, 78th Infantry, fired their grenade dischargers all along their attacking line and charged forward to Company G's defenses.

Major Kawahigashi led his men in the attack. In the moonlight he could see forty or fifty meters, about halfway across the river.

His men had crouched along the eastern riverbank for about five minutes before they heard a battalion gun open fire. Into the riverbed they went, and suddenly a tremendous roar of artillery fire crashed around the battalion. The artillery fire splintered trees like matchsticks along the east bank, and the sheared limbs and trunks plummeted to the ground, crushing or pinioning Japanese troops in the forward platoons of the second echelon who had not dug themselves into the earth. Screams, explosions, and noise punctured the darkness. Once the firing had erupted, the three or four Americans sharing a single large foxhole rapidly fanned out, running or crawling to their individual emplacements, and began shooting into the densely packed Japanese infantry.

The American defenders in Company G who had time to look across the river saw the astonishing sight of hundreds of Japanese soldiers screaming and waving their arms as they lunged through the shallow water or pulled themselves up the riverbank. Artillery explosions had stripped away the canes and reed cover, exposing massed targets for American machine gunners and BAR men. Machine gun barrels turned red hot from constant firing, and still the Japanese charge would not be stopped.

Kawahigashi's men then ran into barbed wire strung low to the ground just in front of Company G's perimeter. Many were entangled, slowed, and killed as they struggled to free themselves. The attack by the 78th and 80th regiments hit near the company boundaries of Companies G and E, so the fighting spilled over to E's sector, where an intrepid BAR operator fired twenty-six magazines, more than 500 rounds, in a period of fifteen minutes into the massed Japanese attackers. Even when his weapon overheated, this anonymous infantryman continued to fire single shots into the Japanese troops. According to his company commander, this one man was instrumental in breaking up the first two enemy attacks against Company E.

Friendly artillery was falling so close to the American positions that men on the firing line would instinctively duck their heads as the shells flew overhead. Shrapnel, rocks, and pebbles from the explosions showered the American lines. When the Japanese first echelon finally did break into Company G's perimeter, American automatic weapons fire killed the Japanese captain commanding the battalion machine gun company leading that last-ditch charge. The Japanese attack broke, and the survivors retreated to the east bank.

Of the 400 men who had started across the Driniumor, only ninety remained.

To the left of the 1st Battalion, 78th Infantry, the regiment's 3d Battalion soldiers watched horror-struck as the American artillery blasted Japanese soldiers along the Driniumor. Maj. Koike Masao, the battalion commander, saw Kawahigashi's men advance into the sheets of flame spurting from the American positions. Then it was Koike's turn, and he led his battalion across. Again artillery fire ripped into the Japanese ranks, shredding limbs and torsos. Despite the carnage, the 3d Battalion managed to get across the river in Company E's sector and pass through holes in the American line shortly before midnight. The rest of the 78th Infantry Regiment followed, except for the pitifully few survivors of the 1st Battalion, who tried again and again to break the Company G positions. Their otherwise futile attacks might have distracted Company G just sufficiently to permit the 3d Battalion to reach the west bank.

Farther to the north, near Kawanakajima, Major Yamashita was also leading his 1st Battalion, 237th Infantry, into the river. Two machine gun squads had arrived just one hour before his attack, but he had no idea of the whereabouts of his battalion artillery and its crews. Regardless, he had to get his troops across the Driniumor. Along the densely packed, 100-meter front, the three companies of the Japanese first echelon were halfway across the river when the second echelon began its passage. The second wave of Japanese, two infantry companies, drew scattered tracer rounds from Company E's positions.

One by one, Japanese machine guns began to lay down suppressive fire for the skirmishers. Suddenly, from the south, where Yamashita knew the 20th Division attack was underway, came the thunder of artillery explosions. The Americans seemed to remember that a bugle sounded, but that is doubtful. Then everyone seemed to open fire. Japanese artillery hit just to the rear of Company E's thinly held lines. Japanese blue tracers streaked across the Driniumor, appeared to converge with the red and yellow tracers fired by the Americans, and then split off on their deadly paths. Flares burst over the river.

Company E's commander, Captain Bell, thought that the Japanese had fired the flares because they burst directly over his command post and company mortar positions. Major Yamashita, conversely, believed that the Americans had fired the flares to illuminate his attacking forces, which were now exposed massed in attack. Under the eerie light, which caused shadows to flicker and dance, turning trees and bushes into enemy soldiers, American artillery shattered Japanese formations. The men of Company E struck the screaming Japanese with small arms and automatic weapons fire. Four Japanese heavy machine guns, in turn, raked the American lines, concentrating their fire on Company E's now revealed machine gun and automatic weapons positions.

Major Yamashita heard Japanese soldiers shouting that their machine guns were running low on ammunition. The pandemonium reached a crescendo as human screams, shouts, curses, and crashing artillery accompanied by the popping and banging of small arms fire combined to create acoustics for the tracers and flares. During a brief lull, as flares temporarily flickered out, Yamashita heard more reports of small arms fire to his north and realized that his 6th Company had engaged the Americans.

The roar resumed. Trapped under the massed American firepower, Yamashita's 4th Company veered south, the wrong direction. The din of battle was too loud for them to hear other Japanese soldiers screaming to turn back. The unlucky 4th Company reached Kawanakajima and began to cross the little island. Company E defenders loosed another sheet of small arms fire that knocked down almost the entire 4th Company and turned the island's pebbles blood red under the brightly burning flares. Yamashita still heard reports of heavy firing from the south, which meant to him that the 20th Division had not reached its objectives.

After the destruction of 4th Company, Company E defenders believed that the Japanese attack had then shifted to their north, but in fact, that had been the original Japanese plan. Yamashita led the remnants of his 1st Battalion across the Driniumor and over its western bank. The rest of the 237th Infantry followed shortly thereafter. As American artillery and mortars shifted their fires to repel these breaches, Japanese troops from the 78th and 80th Infantry regiments again struck Company E's southern flank. Visibility deteriorated as the flares were nearly used up, and smoke, debris, and dust from artillery explosions drew a grayish pall, stinking of cordite, over the river. The distance between Company E's strongpoints was too great to cover all the gaps. Their small arms ammunition was depleted, artillery fire had shifted to other targets, and although firing at ranges down to 135 meters, the company's 81-mm mortars alone could not stop the renewed Japanese assault. Company E was overrun.

Japanese infantrymen broke through Company E's line, rushed into and through the American command post and mortar positions, and then started to regroup in order to move inland to the high ground southwest of the main attack sector.

The 1st Battalion, 78th Infantry, suffered terrible losses, 290 men out of 360 effectives, and altogether about 600 men of the 78th Infantry died in the breakthrough. The 237th Infantry had also picked its way through openings in Company E's extended front and worked northwest toward the Americans' rear. Badly mangled by American artillery, the 237th attackers' efforts to regroup in the jungle at night, after such a ferocious hour-long battle, proved beyond them. Instead, small groups of Japanese and American infantrymen isolated or encircled one another in turn along a 1,100-meter-wide opening that a few hours previously had been the front line for Companies E and G.

Company E lost perhaps ten killed and another twenty wounded before it exhausted its ammunition and pulled back from its defensive positions. Its contingency withdrawal plan was impossible because of the chaos, darkness, and lack of communication. All land lines had been severed an hour before, either by U.S. artillery or by Japanese troops. Suffering about 30 percent casualties and overrun, Company E was thoroughly scattered and, as far as higher headquarters could determine, had ceased to exist.

The disintegration of Company E meant that Company G's left (north) flank was wide open. The company commander, Capt. Ted Florey, thus put his reserve platoon on the open flank to continue his makeshift line back to the battalion mortar positions. Until 0400 on 11 July, heavy enemy small arms fire and irregular mortar or artillery fire struck the Americans, but after that, quiet ensued. About 0200 Company G lost contact with higher headquarters, but could communicate through the artillery liaison officer's radio. Shortly after dawn, with "no reserve to restore the break in the line," General Martin ordered Florey to withdraw to River X, about 4,500 meters to his west. Company G, plus assorted units and remnants of Company H, spent the next three days marching and fighting those 4,500 meters. They were alone, exhausted, and afraid. The Japanese 78th and 80th regiments were in similar straits, and their officers and NCOs were urging them to move southwest to mop up the rest of the American covering force.

That Japanese enveloping maneuver brought them into contact with the 112th Cavalry near Afua.

112th US Cavalry 1944 Covering Force in New Guinea

-

Introduction

Druniumor: 18th Army Prepares to Attack

Breakthrough of the Japanese Attack

US Counterattack at Afua

TO&E vs. Actual Unit Strengths

US and Japanese TO&Es (slow: 98K)

Jumbo Map of New Guinea (slow: 192K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Combat Simulation Vol 2 No. 2

Back to Combat Simulation List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by Mike Vogell and Phoenix Military Simulations.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com