Prelude to Disaster

Reno was later to claim that he assumed that Custer intended to follow him in close support, but it seems more likely, that, so far as he had a firm plan, Custer intended to use his detachment either to trap any disorganised Indians fleeing from Reno, or, if their camp was still in situ, follow the practice he had adopted at the Washita, and attack it in flank from across the Little Big Horn. It also seems probable that Reno would have expected this.

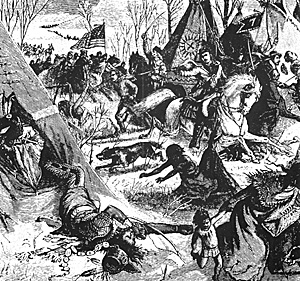

Despite everything, it seems that the Indians in the village were completely surprised by Reno's attack, but, as Reno's men galloped forward, firing their revolvers, increasing numbers of warriors began to ride out to confront them. Though their initial intention may simply have been to buy time for the cover the retreat of the non-combatants in the village, to Reno "the very earth seemed to grow Indians", and he dismounted his men and began a long-range exchange of fire. After about 15 minutes, Reno pulled back to a growth of cottonwoods on his right, and within half an hour, with Indians infiltrating into the woods, in something approaching a state of panic, Reno gave confused orders for his men to retreat across the Little Big Horn to the bluffs on the far bank, where they could occupy a defensive position and link up with Custer. In a withdrawal which fast degenerated into a near rout, with Reno losing all control, many did not make it.

Despite everything, it seems that the Indians in the village were completely surprised by Reno's attack, but, as Reno's men galloped forward, firing their revolvers, increasing numbers of warriors began to ride out to confront them. Though their initial intention may simply have been to buy time for the cover the retreat of the non-combatants in the village, to Reno "the very earth seemed to grow Indians", and he dismounted his men and began a long-range exchange of fire. After about 15 minutes, Reno pulled back to a growth of cottonwoods on his right, and within half an hour, with Indians infiltrating into the woods, in something approaching a state of panic, Reno gave confused orders for his men to retreat across the Little Big Horn to the bluffs on the far bank, where they could occupy a defensive position and link up with Custer. In a withdrawal which fast degenerated into a near rout, with Reno losing all control, many did not make it.

It is not clear at what point Custer realised that Reno had become bogged down. He and his command had been continuing northwards along the bluffs on the east bank of the stream. From the high point later known as Reno Hill he got his first inkling of the full size of the Indian camp, though he does not seem to have been too perturbed. When his men began cheering, Custer told them: "Hold your horses in boys; there are plenty of them down there for all of us."

He sent a Sergeant back with orders to hasten up the pack train; and Custer's brother, Tom, added: "If you see Benteen, tell him to come on quick--a big Indian camp."

At about this time, Custer rode to the crest of a promontory, later known as Weir Point, from which he was able to see that Reno's attack had stalled. He sent another urgent message to hasten on Benteen, and then led his command at a rapid pace down a long narrow ravine, known as Cedar Coulee, which ran northwards, and then opened down into a slightly wider coulee, Medicine tail, which ran down to a ford over the Little Big Horn.

From this point, there are no more direct sightings of Custer's contingent by any American survivors, and Indian accounts were conflicting and misleading for a number of reasons. In general, those made nearest to the event are the most suspect, as those interviewed had every reason to tailor their versions of events to what they thought would best please their interrogators, whilst those remembering later had less reason to alter events.

What now seems to have happened is that Custer halted at the junction of Cedar Coulee and the beginning of Medicine Tail. Here he was joined by his brother Boston, riding back from the pack train, who told him that Benteen was on his way. Meanwhile, two of Custer's scouts, Curley and Mitch Boyer, on the high ground watching for Reno, saw his force routed, and rode down to tell Custer.

Custer felt that urgent action was needed to take the pressure off Reno, so he sent two companies down the Medicine Tail to cross the ford and attack the flank of the Indian camp. At this stage the bulk of the hostiles were involved in the battle with Reno, and the few remaining in the village sent an urgent warning of Custer's approach. Initially, there may have been as few as four warriors defending the ford as Custer's men, probably the companies under Captain George Yates, began to cross. But more warriors began to appear through the trees, and the volume of fire increased.

Fallen Officer

At this moment, an officer in a buckskin suit, riding at the head of the column next to the guidon bearer and the scout, Mitch Boyer, was shot in the chest. Opinions differ as to whether this was Yates or a subordinate, or whether it could have been Custer himself. The latter is certainly possible, though those soldiers who saw him earlier in the day say he was not wearing his jacket, but certainly his body, when recovered, bore a probably mortal chest wound. If Custer was indeed hit at this point and left dead or dying, it would certainly help explain the collapse in command control which was to follow.

Whoever the officer was, his fall caused confusion; other soldiers clustered around him, and as more Indian reinforcements began to arrive, the soldiers fell back across the ford in growing confusion.

Myles Keogh's battalion had been left holding the high ground at the junction of Medicine Tail and Deep Coulee, where they could link up with Benteen, but now found themselves engaged with some Hunkpapa Sioux, led by Gall (at right), which were advancing up the Medicine Tail Coulee. Yates's men had meanwhile dismounted, and were conducting a fighting retreat up the north slope of Deep Coulee to the southern end of Battle Ridge.

Myles Keogh's battalion had been left holding the high ground at the junction of Medicine Tail and Deep Coulee, where they could link up with Benteen, but now found themselves engaged with some Hunkpapa Sioux, led by Gall (at right), which were advancing up the Medicine Tail Coulee. Yates's men had meanwhile dismounted, and were conducting a fighting retreat up the north slope of Deep Coulee to the southern end of Battle Ridge.

Having repelled his attackers, Keogh led his three companies northwards to link up again with Yates's two companies, but after he had dismounted his men, lost his horses when the Indians stampeded them. Custer's force was now in serious difficulties, and whether or not Custer was still in command, or dead or dying among his men, signs of disintegration were beginning to appear. They may have made a last effort to counterattack, sending C Company southwards in anew effort to reach a ford, but such an attempt, even if it was made, was doomed from the start.

Rapid Disintegration

Disintegration was now rapid; the length of the last phase of the battle has been variously estimated, and again confusion results from the attempts by some of those serving with Benteen and Reno to convince contemporaries that all was over before they could possibly have intervened. It has been said that resistance lasted no more than 20 minutes, and certainly cohesion seems to have been quickly lost.

No coordinated defence line was formed, the companies standing and dying individually. The degree of resistance which they put up also varied. Red Horse, a Miniconjou Sioux engaged in the final battle, later recalled: "these soldiers became foolish, many throwing away their guns, and raising their hands, saying Sioux, pity us; take us prisoners. The Sioux killed all of them."

There were also reports that many of Custer's men, possibly even including the General himself, committed suicide. This is in fact entirely possible in some cases, as it happened on other occasions, though forensic research in recent years has not provided any hard supporting evidence.

So far as can be deduced, resistance seems to have varied; Calhoun's C Company appears to have put up a fairly organised stand (based on the rather unreliable evidence of the pattern of grave markers, and the more convincing pattern suggested by finds of cartridge cases and equipment). Fierce hand to hand fighting occurred when E Company turned their horses loose and charged the Indians, firing wildly. But what has been made increasingly evident by archeological research is that the troops, with their single-shot breechloading carbines, some of which jammed, were not only outnumbered 6 or 7 to 1, but also considerably out-gunned. It has been estimated that at least half of the hostiles possessed firearms, and that 25-30% ( about 370) may have had repeater rifles. These two factors alone are sufficient to explain Custer's defeat.

E Company was quickly overwhelmed, and the Indians thrust into the ensuing gap between L and I Companies. Companies were probably down to an effective strength of 30-40 men, and it probably only took the Indians, now aided by a swinging blow from the North east led by Crazy Horse, which broke against the rear of Custer's men, a few minutes to overcome each company.

Custer's already disordered units rapidly broke up into smaller and smaller knots of struggling men, and it may have been among these as the Indian boys and squaws began to move in on the wounded on the fringes of the fight, killing and mutilating, that suicides occurred.

The final organised resistance took place on Last Stand Hill, where about 50 men, probably mainly Tom Custer's C Company, and the staff, accompanied, whether (lead or alive is uncertain, by Custer himself, made a breastwork of their horses, and went down fighting.

The final organised resistance took place on Last Stand Hill, where about 50 men, probably mainly Tom Custer's C Company, and the staff, accompanied, whether (lead or alive is uncertain, by Custer himself, made a breastwork of their horses, and went down fighting.

The exact timing of these events is uncertain. If Reno began his attack on the southern end of the Indian village at about 3 p.m., or perhaps a little earlier, then Custer's abortive attempt to cross the Medicine Tail Ford may have been about 3-45 p.m, and the "Last Stand" itself may have been over by 4-30 p.m. This is borne out by the testimony of the officers of Reno and Benteen's commands.

Benteen, after some apparent hesitation what course to adopt, had joined Reno on the bluffs, and possibly at Reno's urging, had decided to stay and support him. Reno refused to consider moving to assist Custer until all of the ammunition had come up, though in justice to him, none of his officers, despite hearing some firing (exactly how much is disputed) seem to have felt that the General was in difficulties. However, against orders, Captain Weir did lead his troop forward to Weir Point, and on top of Custer Hill, saw some horsemen waving cavalry guidons.

A sergeant told him that they were Indians, which seems likely, and Weir dismounted his men. It may now have been about 5 p.m., and it has been suggested that Custer was still holding out. This seems doubtful, though even when Benteen and Reno arrived shortly afterwards, some shooting was still going on.

All of the officers involved were to be reticent in their descriptions of what they could see, leading to suspicions of a "cover-up". More likely, in the dust and confusion, they could distingush very little, but were anxious to avoid giving the impression that they might have saved Custer. In reality, apart perhaps for a few wounded, Custer and his men were almost certainly already dead, and any intervention by Benteen and Reno would have led to the loss of their men as well. They withdrew to Reno's old position, and, in a postscript to the battle proper, were to hold out all night, and, with less difficulty, all the next day, until relieved by the arrival of Terry and Gibbon.

Not until the morning of June 28th did Reno's men venture onto the scene of the last stand to begin roughly burying the dead. It has been estimated that only about 10% of Custer's men had been fortunate enough to be killed outright by enemy fire. The remainder, wounded, were finished off more or less quickly by Indian warriors or their women and children. Mutilation was virtually universal.

Not until the morning of June 28th did Reno's men venture onto the scene of the last stand to begin roughly burying the dead. It has been estimated that only about 10% of Custer's men had been fortunate enough to be killed outright by enemy fire. The remainder, wounded, were finished off more or less quickly by Indian warriors or their women and children. Mutilation was virtually universal.

It was said at the time that Custer himself was unmarked apart from bullet wounds to the head and chest, but there are grounds to believe that his body may actually have been mutilated as well. He was not scalped again despite the legend, Custer "Long Hair", actually had receeding hair, which was cut short for the campaign, so that the Sioux and Cheyenne did not think he was worth scalping, and in any case, not knowing that they were fighting Custer, did not recognise him anyway.

The Battle of the Little Big Horn was of no long term military significance; the Sioux had neither the means nor the ability to follow up their victory, and were mostly hunted down by the following spring. But the events of June 25th 1876 have generated a continuing controversy which, over a century later, shows no sign of dying down. It is perhaps a greater posthumous fame than even that great self-publicist, George Armstrong Custer, could have hoped for.

TWO CAVALRYMEN VISITING GRAVES AT THE SITE OF THE BATTLE OF THE LITTLE BIGHORN.

TWO CAVALRYMEN VISITING GRAVES AT THE SITE OF THE BATTLE OF THE LITTLE BIGHORN.

More Last Stand at the Little Big Horn

-

Introduction and Background

Custer's Order of Battle, June 25th 1876

The Campaign

Battle of Little Big Horn

Jumbo Color Map of Battlefield (monstrously slow: 601K)

Back to Colonial Conquest Issue 8 Table of Contents

Back to Colonial Conquest List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1996 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com