The Little Big Horn Campaign of 1876, and in particular, the events leading to the deaths of General George Armstrong Custer and over 200 men of the 7th Cavalry at the hands of the Sioux and Cheyenne have been the subject of a vast literature, good, bad and indifferent, and a host of theories and reconstructions, equally variable in value.

The Little Big Horn Campaign of 1876, and in particular, the events leading to the deaths of General George Armstrong Custer and over 200 men of the 7th Cavalry at the hands of the Sioux and Cheyenne have been the subject of a vast literature, good, bad and indifferent, and a host of theories and reconstructions, equally variable in value.

At right: Custer and Sitting Bull

This article will not attempt to retell the story of the campaign in detail ( the titles listed under "Further reading" are mostly readily available) but will aim to explore some of the legends which have grown up, particularly concerning the "Last Stand" itself.

The Great Sioux War of 1876-77 became inevitable two years earlier after gold was discovered in South Dakota in the Sioux territory of the Black Hills. Friction was already growing as a result of treaty violations by both sides, and the large numbers of settlers encroaching on Sioux territory in search of gold provided a flashpoint. The U.S. Government, not averse to an opportunity to settle the problem of the inconvenient Plains Indians once and for all, turned a blind eye to the encroachments of the prospectors, and the Indians hit back with a series of raids.

Matters were brought to a head in December 1875, when the Government issued the Sioux with a completely unrealistic deadline by which they were to return to their reservations, and with their failure to comply, in 1876, the issue was handed over to the Secretary of War to be settled by force.

Strategy

The strategy decided upon by Lieutenant-General Phillip H. Sheridan, commanding the Department of the Missouri, and Brigadier-General Alfred H. Terry, of the Department of Dakota, involved the deployment of three columns of troops to enmesh the hostiles, bring them to action and destroy them. Though it is sometimes suggested that the American commanders hoped to unite their forces before fighting the decisive battle, both the vast distances involved, the illusive nature of the foe, and the limitations of available communications made such an outcome unlikely, and each column was intended to be strong enough to deal single-handed with any enemy force likely to be encountered.

The strategy decided upon by Lieutenant-General Phillip H. Sheridan, commanding the Department of the Missouri, and Brigadier-General Alfred H. Terry, of the Department of Dakota, involved the deployment of three columns of troops to enmesh the hostiles, bring them to action and destroy them. Though it is sometimes suggested that the American commanders hoped to unite their forces before fighting the decisive battle, both the vast distances involved, the illusive nature of the foe, and the limitations of available communications made such an outcome unlikely, and each column was intended to be strong enough to deal single-handed with any enemy force likely to be encountered.

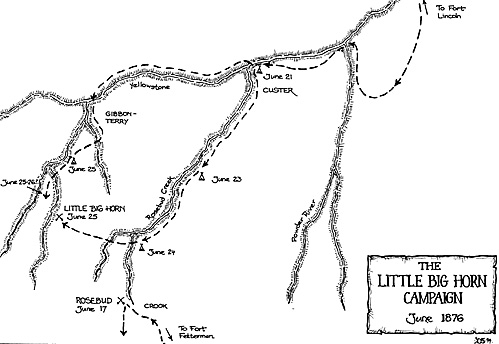

Initial operations were frustrated by bad weather and failure to contact the enemy, but operations were resumed in May. General Crook was to move north from Fort Fetterman in Wyoming, Colonel John Gibbon would march eastwards from Fort Ellis in Montana, whilst General Terry, the column spearheaded by Custer's 7th Cavalry, would push eastwards from Fort Abraham Lincoln in Missouri. Further delays were caused by command problems, notably President Grant's initial refusal to give a command to Custer because of accusations of corruption which the General had made against members of the Government, and it was not until May 17th that Terry's column got under way.

The results of the first stages of the campaign were disappointing; Gibbon fumbled his part, moving hesitantly along the Yellowstone River, seemingly avoiding contact with hostiles known to be in the vicinity and sending apparently misleading reports of their whereabouts to Terry. Crook's operations also got off to a slow start, and were brought to a complete standstill by his mauling at the Rosebud on June 17th.

So, although still unaware of Crook's reverse, Terry, finally united with Gibbon, was faced with a frustrating situation when, on June 21st, he called a conference at his base on the Yellowstone River to consider his next move. Information concerning the whereabouts of the hostiles was still vague, though reports indicated an encampment 20 or 30 miles up the Rosebud. It was decided therefore that the force would once again split into two columns; Gibbon, accompanied by Terry himself, would move southwards along the valley of the Little Big Horn, the intention being that if it did not itself encounter the enemy, it could prevent them escaping to the west away from the second column. This was to be commanded by Custer, and would march first up the Rosebud, moving deliberately so as not to panic the enemy into flight before Gibbon was in position to block them, and then swing westwards in the general direction of Gibbon.

It was recognised that either column might have to fight the Indians on its own, but this prospect did not cause anxiety. It was generally assumed that, because of problems of supply and normal Indian disunity, no large enemy force would stay together for long, and that in any case, the hostiles' maximum force was not likely to exceed 1,500 men. Either column should be able to handle them.

In reality, when Custer left Terry at noon on June 22nd, it was recognised that it was very likely that he would encounter the enemy on his own, and bring them to battle. Despite the probably deliberately vague nature of his orders, and later denials, it is clear that Terry and his officers expected as much. One of them, Lieutenant James Bradley, wrote in his diary on June 21st that it was understood "that if Custer arrives first he is at liberty to attack at once if he deems prudent. We have little hope of being in at the death, as Custer will undoubtedly exert himself to the utmost to get there first and win all the laurels for himself and his regiment".

Such an outcome could have been expected by anyone familiar with the character of George Armstrong Custer. He had first proved himself as a leader of cavalry during the American Civil War, exploits magnified by Custer's skills as a self publicist, and he had gone on to build on this reputation during the earlier Plains Wars. Closer examination would however have raised a number of doubts; for example, Custer's "victory" on the Washita River in December 1867 had resulted basically in the massacre of a number of Cheyenne women and children in an undefended camp, and because of command confusion, some of Custer's men had been abandoned and massacred. Custer's record showed a number of disturbing questions regarding his ability for higher command, and it it something of a mystery that Sheridan and Terry should have made such impassioned pleas for him to be allowed to take part in the campaign.

Credit for Presidency?

It is also the case that Custer set off on June 22nd in great need of a success to restore his somewhat tarnished reputation and secure his position. Almost certainly untrue, however, is the suggestion sometimes made that Custer was desperate to win a triumph which would lead to his being adopted as Democratic Presidential candidate by their convention currently meeting in St Louis. Quite apart from the question of whether any victory over the Sioux would have rated such importance, there is no reliable evidence that Custer had voiced any such ambition, and the state of communications was such that word of any victory could not have reached the convention in time.

Custer was however quite resolute that the credit for any victory should go to the 7th Cavalry, and said as much when he rejected Terry's offer to reinforce him with four companies of 2nd Cavalry, saying that 7th Cavalry could handle any opposition which it was likely to encounter, and that "I want all the glory for the 7th Cavalry there is in it." He also turned down the offer of a Gatling battery, which in any case would have probably been an impractical encumbrance. Once again, it is possible with hindsight to criticise Custer, but the reality was that most of his contemporaries would have agreed that the 12 companies of 7th Cavalry should have been more than adequate to deal with any likely opposition.

The 7th Cavalry was neither as good nor as bad as it has sometimes been portrayed. Though the 1876 campaign was the first occasion on which all of its companies had served together, this was not unusual on the Frontier, and Custer had made strenuous efforts, with some apparent success, to build up regimental espirit de corps. That said, the fact remains that Custer was far from universally popular among his men, as suggested by his nickname of "Old Ironass".

The regiment was somewhat short of officers, and those present certainly varied considerably in their ability. Much has been made of the rivalries among them, particularly between Custer, Major Reno and Captain Benteen, but this again was not exceptional, and was distorted and magnified by the events of the battle, and the need for self-justification among the survivors.

So far as the rank and file were concerned, while it is the case that half of G Company and a third of A Company consisted of raw recruits, the average length of service in the regiment as a whole was a respectable four years. It was said of them that "the men had had very little training; they were very poor marksmen and would fire at random. They were brave enough, but had not had the time or opportunity to make good soldiers." Again, this description could have been applied to any Frontier cavalry regiment, and cannot have been entirely applicable to the more seasoned soldiers. All in all, therefore, the 7th Cavalry had as good a chance of success as any other unit of the Frontier army.

More Last Stand at the Little Big Horn

-

Introduction and Background

Custer's Order of Battle, June 25th 1876

The Campaign

Battle of Little Big Horn

Jumbo Color Map of Battlefield (monstrously slow: 601K)

Back to Colonial Conquest Issue 8 Table of Contents

Back to Colonial Conquest List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1996 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com