Another interesting issue in war games is how to represent these battles, in which the side having the strategic initiative (Union) is the defender in the tactical sense. In games having large zones, such as Grand Army of the Republic, it is clear that the Union force must be (in a game sense) the attacker. This game was chosen as a representative to illustrate this point.

GRAND ARMY OF THE REPUBLIC:

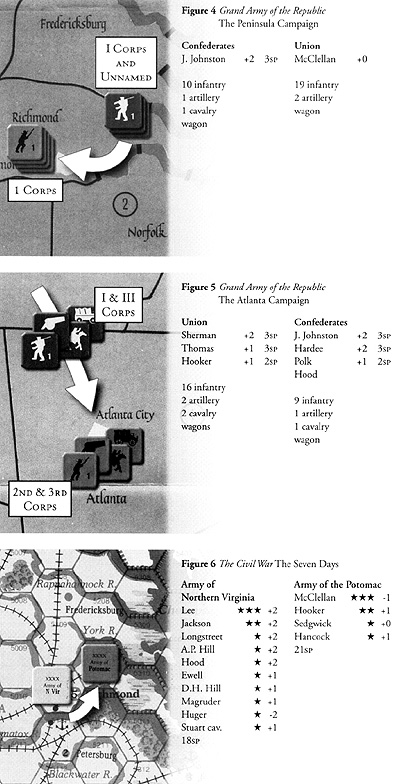

THE PENINSULA CAMPAIGN

In this particular game, the Seven Days campaign is lumped in with Yorktown, Williamsburg and the rest of the peninsula campaign: McClellan is the attacker, and loses about 7SPs while inflicting about 5SPs, and then presumably chooses to retreat. If the Southern force is credited with Longstreet or Lee, the Union losses are higher. The historical campaign saw heavier Confederate losses than Union, yet it was the Union army that retreated.

The historical result cannot occur in the game, since a larger Union army inflicting higher proportionate losses than it takes has no reason to retreat and everything to gain by maintaining the attack. (The Union does not have a supply problem here. I assumed results of "battle cards" would be a net wash.) Note that Lee, and the reinforcements that came after he took command, simply do not enter the picture. Possibly you could assume Johnston retreated out of the zone, and Lee counterattacked back into it. Note that the game uses "Corps" to designate organizations that are typically smaller than the historic corps, but often not as large as armies; the numbering is arbitrary.

THE ATLANTA CAMPAIGN

In the same game, the Atlanta campaign consists of Sherman advancing into the Atlanta area against J. Johnston. Average losses in one round of combat are 7 SP each, after which the Confederates obviously retreat (to the Decatur zone, preparing to advance on Nashville). If you credit the Confederates with being entrenched (at least Johnston's troops, perhaps not Polk's) the Confederate losses are a bit lower.

This is not a bad approximation of the overall campaign results. The resolution necessary to represent the tactics of defending Atlanta, and of the difference between Johnston's and Hood's phases in the defense, is beyond the scope of this game.

Victory's Civil War and Clash of Arms' The War for the Union use hexagons of about 25 miles per hex (slightly smaller for the latter). All of the fighting for both campaigns could be considered as taking place within one hex, though separated in time into separate "battles."

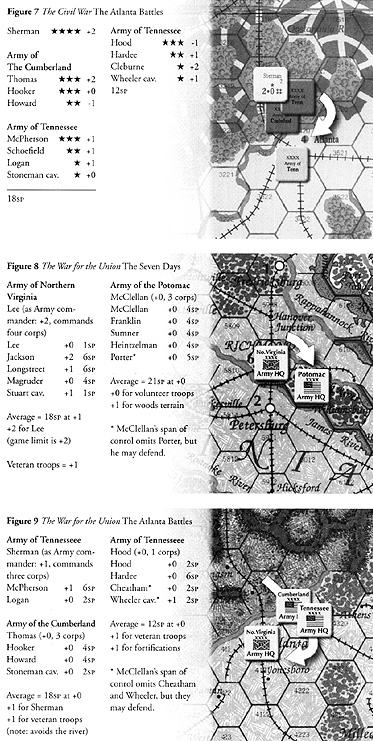

THE CIVIL WAR:

THE

SEVEN DAYS

THE

SEVEN DAYS

We consider Victory's Civil War first. If we accept that the armies maneuver in monolithic wholes, then our representation of the Seven Days consists of Lee attacking McClellan, who is adjacent to Richmond. (We include the historic reality of Huger's presence, though no sane Confederate player would have failed to exile Huger by this time, however. At the very least he should have been left in Norfolk with 1SP

With this game's mechanics, in this situation he is much more of a liability than Jackson and Longstreet together are a credit.) With a +12 to the die roll (too much to be useful), the Confederates inflict at most "d2" (demoralized and -2 Strength Points, or SPs), and with 4 re-roll options should manage to get that result. The Union force (with +4 including Huger but not Meade) inflicts d3 losses on the Confederates. (There is no chance of other results.) If we model the campaign as two consecutive Confederate attacks, this could happen twice, with results that are close to historical in terms of losses, but without having forced the Union withdrawal. Of course, no Confederate player in the game would make such an attack.

One feature of this game is the use of abstract "Action Points" that are used to "activate" generals. Action points are limited. It takes only 2 to activate Lee, Hood, or Sherman, but 3 for McClellan and most other generals. The same number of action points is needed to remove demoralization. Thus, it is very possible for Lee, Hood, or Sherman to attack, undemoralize, then attack again, perhaps repeatedly, in one two month long turn. It also is possible for this to happen before the opponent gets to do anything. The system has the negative that the player, representing the national command (President) is put in the role of prioritizing between actions in different theaters that should in many cases be simultaneous and autonomous. It also makes more than two player gaming more difficult.

THE ATLANTA BATTLES

Looking on Atlanta similarly we find Sherman, who as a 4 star general can carry multiple armies, advancing on Atlanta. Considering Atlanta's defenses to be "Entrenchments" (rather than a fortress), and assuming that Sherman has managed to cross the Chattahoochee (as shown) before the battle (no -1 column shift), then the Union army inflicts d2 or d3, while the Confederates inflict d2 to d3, in both case with a 50% chance for each. With the Union getting 3 reroll options, the result is probably d2 Union and d3 for Confederates. This would force the Confederate army out of Atlanta.

If we assume bad Union luck requiring two attacks (with a recovery from demoralization in between) then the second attack might raise casualties to historic levels. If we assume Atlanta is a fortress, the extra column shift very slightly affects the Confederate losses, and allows them to avoid retreat until attacked a second time. If they are still demoralized when Sherman attacks again, the retreat is forced. This might be the most accurate representation of the series of battles around Atlanta from a losses perspective, but you notice that we have had to assume that it is Sherman who is attacking, not Hood, and maneuver is not much of a factor.

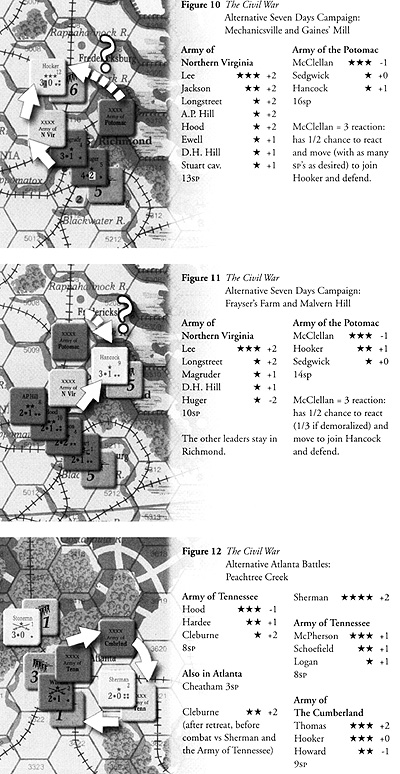

THE WAR FOR THE UNION

THE SEVEN DAYS

THE SEVEN DAYS

In The War for the Union, there is not quite as much motivation for armies to maneuver as monolithic wholes, since an attack can include forces in other hexes (although at 1/2 strength) and all leaders can move at the same time, prior to combat, not just a single one. The army commander's benefit can count for (his) corps commanders not in the same hex. In contrast, combat in Victory's "Civil War" occurs as a consequence of movement by a force under the command of a single leader. This is a powerful motivation against making detachments.

McClellan's army in The War for the Union is shown A in one hex, attacked by Lee from Richmond, as for The Civil War. Lee has two chances in six to force McClellan to retreat (but in both cases takes no more losses than McClellan does) and one chance to be forced to retreat and thus abandon Richmond (or be forced to retreat into a fort, if there is one).

Lee's casualties will probably be the same as McClellan's (3 to 4 Sp's), with one chance of being 1SP lighter. If Lee succeeds in forcing McClellan to retreat, he can attack again and take more losses. This is a reasonable interpretation of what happened. As with The Civil War, Confederate losses are probably lighter than the historical result, although there is at least a chance to displace McClellan.

In this game it makes sense under some circumstances for the army to split up and attack from multiple hexes. In this case, for example, Jackson could move to and attack from the hex just North of McClellan, and still receive the benefit of being under Lee (since he is adjacent). He would be x 3/4 in strength for the minor river. Likewise, another lieutenant might be in Petersburg (but halved for the navigable James river). Some such diversion of strength can be afforded without being bumped down a column on the Combat Results Table.

Historically, everything happened in one hex. A case could be made that McClellan actually entered the Richmond hex, but that would, in the game's rules, require that Johnston retreat into Richmond fortifications to endure siege. But McClellan never established a siege in the sense of what the term means in the game rules.

In any event, Lee is too strong to be besieged. Thus, the simple attack as shown here most closely represents the historic event. (Note that the minor river shown is the York and its tributaries, not the Chickahomony that actually divided McClellan's force.)

Sherman and Hood around Atlanta would again be all within one hex, that containing Atlanta, except for the final move to Jonesboro. While Atlanta might be considered to have a Fort, Hood does not retreat inside (to endure siege and eventual surrender), so the representation of the battles must be an attack by Sherman on Hood, who is in the Atlanta hex. Sherman has a 50% chance of forcing Hood to retreat, and 2 of 6 chances of incurring lighter casualties (both of which involve Hood's losing Atlanta). There is no possibility of Hood losing more heavily but holding on to Atlanta, as actually happened, except for the unhistorical possibility of his choosing retreat into the city and enduring siege in the sense of Vicksburg.

THE ATLANTA BATTLES

Just as in the Seven Days situation, Sherman could leave some troops on the North side of the Chattahoochee, but then they would be attacking at 3/4 strength due to the river. This would drop Sherman a column on the Combat Results table, and he wouldn't want that. Historically, all of the fighting, and maneuvering, was on the South side. The stream involved was Peachtree Creek, which is too insignificant for this scale. Indeed, eventually almost all of Sherman's force passed between Atlanta and the Chattahoochee before Hood abandoned the city after Jonesboro.

An interesting difference between these two games is the selection of leaders. In The Civil War only particularly interesting leaders are included, including division commanders with unusual abilities such as Jackson, Sherman, Sigel, and Huger. Porter, Heintzelman, McCook, and the mass of other Union Corps level leaders are omitted. In contrast, The War for the Union omits division commanders and includes almost all corps commanders. As a result, in The Civil War some leaders like Sigel and Huger are there only to be a nuisance with almost no possibility of being of any real value. In The War for the Union even the less capable leaders can typically serve a useful purpose.

In both The Civil War and The War for the Union, we could consider taking some liberties with the sense of scale, to assume that the maneuvers take place not just in one hex but also in some of the others surrounding the city of concern. The Union player could divide his force to maneuver towards the city's supply lines while protecting his own communications with a smaller (but presumably entrenched) portion of his force.

Likewise, the defending army might sally out with only a portion of its force in order to counterattack from a hex that makes reaching the city's rear more difficult, while holding the city with the remainder. This is more the character of how these campaigns played out. However, it requires some exaggeration of scale, and is discouraged by the rules, especially by the Action Point and Reaction rules of The Civil War.

In The Civil War, the only logical division of McClellan's army before Richmond is extension of a portion into the hex directly north of Richmond. In that hex it is protected by river hex-sides. In fact, Porter's 5th corps did attack a Confederate detachment that would be in this hex, but did not stay there. With some exaggeration, we could treat this hex as being the Union army north of the Chickahominy.

Since this game does not have a Porter, we use Hooker instead, the only Union leader marker other than McClellan at the scene who can lead 6SPs. Lee would then leave Magruder and Huger with 5SPs entrenched in the Richmond hex and attack with Jackson, Longstreet, D.H. Hill, AT Hill, and Stuart. With 13SPs against about 6, and a leadership bonus of + 11 (vs. +1 for Hooker) and 3 rerolls, this is a wipeout: The Union detachment of 6SPs loses 3SPs, is forced to retreat, and demoralizes the rest of the Union army assuming it retreats southeast.

The Confederates may lose nothing, and have only a small chance of being demoralized. That is, this is the outcome unless McClellan makes his reaction roll (1/2 chance) and sends help.

ALTERNATIVE SEVEN DAYS CAMPAIGN: MECHANICSVILLE AND GAINES' MILL IN THE CIVIL WAR

Let's assume McClellan does react, with a small force (equivalent to Sedgewick react ing with a few SPs to prevent 2-1 odds, as happened at Gaine's Mill). Now Lee still wins, but the casualty ratio is somewhat favorable, and there is a somewhat greater chance of demoralization. If McClellan reacts instead with most of his army, let's say 10 SPs, then Lee's attack is at -3 (with a further -1 column shift to 1 to 2 for terrain) and it will be guaranteed that both are demoralized.

The Confederates may lose more heavily, d3 vs. d2 for the Union. In that case there are still 5 SPs (possibly entrenched, in woods, hopefully with a decent leader, we assume Hancock) guarding McClellan's communications to the James. (Actually this is a problem, in that Hancock at this point can move only 2 SPs, not the 6 allowed for a two star general. He still benefits defense without problem, and if Lee actually attacks this force, there will be but 2 SPs left afterwards anyway.)

Let's assume Lee gets the action points (it only takes 2) to recover from demoralization after an unsuccessful attack on most of McClellan's army north of Richmond. He will still be in the Richmond hex, having retreated there. He can now leave Jackson, AT Hill and D.H. Hill and 4SPs (if we want to follow history) facing McClellan in Richmond and attack the smaller force (we can imagine this is at Frayser's Farm and Malvern Hill) with Longstreet, Magruder, and Huger and maybe 10 SPs, enough to give a 2 to 1 ratio. (if Lee had been in another hex, the rules do not allow him to pick up Magruder and Huger and the 5 SPs in Richmond on his way through.)

McClellan gets a reaction chance (1/3 if he's still demoralized, otherwise 1/2) to react and gets there with help. Historically, you would say he made this roll, and as a result Lee attacked a superior force (all of McClellan's army), which won. Lee's attack is 1 to 2 into woods (but not entrenchments) and is guaranteed a d3 result, while the Union army will likely be demoralized, and may suffer as much as d2. Note that McClellan does not retreat.

And indeed, Harrison's Landing where he camped after Malvern Hill can be thought of as being in that hex. It is reasonable to leave him there. The campaign result, assuming McClellan made his reaction rolls, is 6 SPs lost (30,000 troops) for the Confederates, and about 4 SPs for the Union. Pretty close to history.

ALTERNATIVE SEVEN DAYS CAMPAIGN: FRAYSER'S FARM AND MALVERN HILL IN THE CIVIL WAR

The above narrative is not too bad at explaining the campaign. There is just one major flaw: A reasonably experienced Union player is not going to divide his force as described. The game does not motivate it. indeed, the inability of a detached non-army force to react to, and escape from a moving army, and the very unfavorable losses it would incur even if it survives, makes such detachments foolish. Improved reaction rules, allowing a smaller force a chance to escape, and limiting the combat results table to the smaller size of the two forces involved, would go some ways toward making this more realistic type of campaign more likely.

A further problem is that an army assembled in the same hex can be moved in its entirety using just the leader's command (action) points. But if any units are in a separate hex, they cost additional action points to move equivalent to (or more than) the army's.

This means that they tend to be left behind and unavailable, so detachments tend to be left only in strong defensive positions. Allowing the army (when moving) to include forces in adjacent hexes might help, perhaps at one extra action point each.

Furthermore, the Confederate player in this example is forced to make poor use of leaders in order to stay true to the historical sequence. As mentioned earlier, Huger has no business being here; he is much worse than useless. Furthermore, in the second phase the Confederates leave many good leaders out. Maybe this even makes sense; they only marginally would increase the chances of greater Union losses, and stand a risk of being killed. But this is not a reasonable mechanic.

The combat system proper of this game has some deficiencies that affect the outcomes: Minor (1 star) leaders having a large effect on army combat, loss levels (Small, Medium, or Large) set by force size rather than by either the smaller (or larger) of the two sides, and negative leadership adding to one's own losses rather than subtracting from the enemys.

In conclusion, it is possible to engineer the historical campaign, but only by using moves that a Confederate player would not use, and with McClellan making all of his reaction rolls. The result looks like a Union victory: McClellan is never forced to retreat.

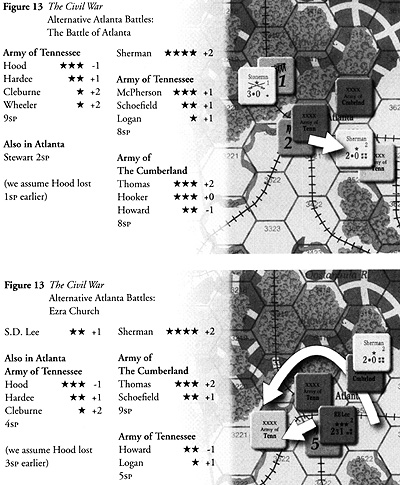

In the same game, an Atlanta campaign could unfold with Sherman leaving Thomas directly in front of Atlanta (but to the northeast to be on the south side of the river). The Union will have left a few SPs directly north of Atlanta to block a move by Hood against the Union communications. Historically cavalry (although not Stoneman) did this job. At the game's scale, it is impossible for Thomas to both be directly north of Atlanta, as he actually was, but also south of the Chattahoochee. Sherman with McPherson swings south and east to land on the railroad. The representation we could have of the Battle of Peachtree Creek requires that Hood attack Thomas from Atlanta while leaving Wheeler (and Cheatham) to guard against McPherson to the East.

This would perhaps put 8 SPs attacking 9, with Hardee (+1) and Cleburne (+2) involved. (Most of Thomas's army and Cleburne did not get into the battle, but they were present as it started.) This gives Hood +4 but -3 rerolls. The most likely result is a "demoralized" and -1 or -2 SP result for both. There is some chance for Hood to win.

If Sherman is present in the hex with Thomas instead of McPherson, Confederate chances are much Slimmer, and they will probably lose d2 to the Union armys I or dl. Note that we are assuming that the Army of the Tennessee does not react. Sherman would have a 2/3 chance of making such a reaction roll. If he does, Hood's attack is very definitely against the odds, has no chance of success, and probably loses d3 to 1 or dl for the Union. Historically, this did not happen. Sherman felt that Thomas was strong enough that he could withstand any attack that might be made against him; he was more worried about McPherson's army. He also knew that he could not get there in time, contrary to what the game allows.

ALTERNATIVE LOOK AT THE ATLANTA BATTLES: PEACHTREE CREEK, IN THE CIVIL WAR

Hood can, after recovering from

demoralization, leave some troops entrenched in

Atlanta and attack McPherson in the Battle of

Atlanta. Hood, with +5 to the die roll and +1

strength advantage to the Union's +3 and

3 rerolls has a reasonable chance of success.

Both forces will be demoralized and lose at least

one and probably 2 SP, but either side might

win. Most likely is a draw that leaves the

Union army in place. There is even a slight

possibility that the Union losses will be 3SP. If

Sherman is not with this wing of his force, the

Union is +2 and 1 reroll, with a bit greater

chance of a Confederate victory. There is a 1/2

chance for Thomas to react and also enter the

battle. That would make Confederate defeat

certain and decisive. Historically he didrA.

Hood can, after recovering from

demoralization, leave some troops entrenched in

Atlanta and attack McPherson in the Battle of

Atlanta. Hood, with +5 to the die roll and +1

strength advantage to the Union's +3 and

3 rerolls has a reasonable chance of success.

Both forces will be demoralized and lose at least

one and probably 2 SP, but either side might

win. Most likely is a draw that leaves the

Union army in place. There is even a slight

possibility that the Union losses will be 3SP. If

Sherman is not with this wing of his force, the

Union is +2 and 1 reroll, with a bit greater

chance of a Confederate victory. There is a 1/2

chance for Thomas to react and also enter the

battle. That would make Confederate defeat

certain and decisive. Historically he didrA.

ALTERNATIVE LOOK AT THE ATLANTA BATTLES: THE BATTLE OF ATLANTA IN THE CIVIL WAR

If we go one step farther to the Battle of Ezra Church, we have Howard (now commanding the Army of the Tennessee after McPherson's death) swinging to the west of Atlanta, which in the game requires a much longer march than it did in reality. Hood sent S.D. Lee to block the way. Lee attacked, losing heavily while inflicting little loss.

In the game, this is a very even fight, with about equal chances for either side to win. Average results are dl to both. Note that we had to assume that Hood did not make his reaction roll (2/3 chance, or 1/2 if we assume he was demoralized). If he made the reaction roll, Howard would be the attacker, and would be crossing the Chattahoochee with a -1 column shift, a battle the Confederates will probably win. (It would be even worse for Howard if Hood reacted to move north.) Note that the cavalry is absent; Sherman has sent his southward and Wheeler gave chase.

ALTERNATIVE LOOK AT THE ATLANTA BATTLES: EZRA CHURCH IN THE CIVIL WAR

Like the maneuvers around Richmond, this sequence appears to offer some chance of replicating the Atlanta city battles reasonably, with Hood attacking Union detachments with real chances of success. As mentioned earlier, the game discourages this kind of division of monolithic armies.

In this case, the fact that both the Army of the Tennessee and the Army of the Cumberland are present makes separate maneuvering more attractive for the Union. But if they are separated, only one gets Shermar~s control benefit, and the action point cost to maneuver the whole force increases greatly. The Union is better off with a straightforward attack by the whole stack on Atlanta.

Notice that in the Seven Days sequence, we only achieved the historical result if McClellan made all of his reaction rolls (unlikely) and reacted with his whole army (historically quite inaccurate). Lee also conducted his battle much less cleverly than an actual Confederate player would. In contrast, the Atlanta series requires only fairly reasonable assumptions to give historic results, and none of the maneuvers are completely unreasonable. Both sides do things that a typical player might not, but note that all of Hood's attacks have some chance of success. One can reasonably conclude that the leader ratings in the Atlanta case reflect the particular situation (including Hood's -I for having just assumed command), while the leader ratings for the Confederates in the Seven Days example are too high, being based on performance later in the war.

It is possible to find similar maneuver options in the War for the Union game. The fact that all leaders can move every turn means that maneuver of a force in separate hexes is more reasonable, and in fact occurs often in game play. Furthermore, the shorter turns and more limited movement means that wide maneuver can happen quite as suddenly without the other player getting a turn in which to react.

On the other hand, there is no reaction mechanism similar to that in Civil War, so that smaller forces are somewhat vulnerable to being swept up by aggregated armies, discouraging maneuver into separate hexes. In the interest of brevity, a detailed analysis of these cases similar to that for The Civil War will be omitted.

There are games that cover the entire war at a finer resolution, in which maneuvers as described above can reasonably be represented. These include SPI's War Between the States (with 1 week turns) and WWW's Mr. Lincoln's War (with 1 month turns). Both require considerable space and time to play, and hence perhaps are less likely to be played. Leader ratings in these games, as with the games addressed here, must cover the entire war, with no provision for leaders improving.

So, for example, Lee in SPI's game starts out as a "4-5-3" (initiative, command span, and combat bonus) compared to "1-5-2" for McClellan, "4-2-2" for Hood, and "4-5-2" for Sherman. WWW has Lee as the sole "3" rated leader, with Sherman a "2" and McClellan and Hood as "1."

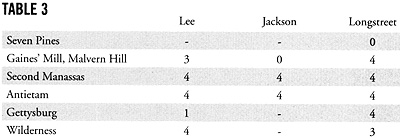

It is interesting to contrast the ratings given earlier with leader ratings in games that cover individual battles. In those games, the designer rates the leaders based on his perception of their ability at the time. One such series, the games of which all have the same rules and which treats leadership very explicitly, is The Gainers' "Brigade Combat Series" covering various Civil War battles. Let's take a look at Lee, Jackson, and Longstreet over the course of several battles:

Here we see that Lee is rated better

later (except Gettysburg) than earlier. If you

consider Confederate command effectiveness to

be the combination of these leaders, you see

that in the Seven Days the low rating for

Jackson also helps make Confederate command

effectiveness significantly lower than it will be

later. The game series has consistent rules but

no obligation to have leaders retain the same

values always, as is typical in theater games.

(Sherman never appears in any series games as

an army commander, and Hood appears once,

with a 0 in Spring Hill and Franklin.)

Here we see that Lee is rated better

later (except Gettysburg) than earlier. If you

consider Confederate command effectiveness to

be the combination of these leaders, you see

that in the Seven Days the low rating for

Jackson also helps make Confederate command

effectiveness significantly lower than it will be

later. The game series has consistent rules but

no obligation to have leaders retain the same

values always, as is typical in theater games.

(Sherman never appears in any series games as

an army commander, and Hood appears once,

with a 0 in Spring Hill and Franklin.)

(Actually, in The Civil War leaders do change, but only with promotions, rather than at the same rank. Knowing who will get better and who will get worse can skew how you handle your leaders, a problem for such a system.)

Command relationships are an intangible that is hard to quantify, and events harder to reduce to a game mechanic. Yet the similarity of these two campaigns, Lee at the Seven Days and Hood at Atlanta, and the similarity of results, argues that the command chemistry is such an important effect that we fail to capture an important reality if it is missing.

Leader ratings for Lee and his lieutenants, based on performance in later battles, tend to overstate the Confederate leadership advantage at the Seven Days. In Hood's case, the ratings tend to stick him in the mode he was in upon just assuming command. The same may be true for some of the Union generals whose tenure was too brief to develop a coherent army high command, as well as Early in the Valley.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

There are many, many books which cover the events described here. The few listed below were of particular use, especially in developing the numbers in the accounts of the various battles.

Thomas L. Livermore, Numbers and

Losses in the Civil War in America, 1861-

65, Morningside, reprint 1987.

Clifford Dowdey, The Seven

Days, The Emergence of Robert E Lee,

Fairfax Press, 1978

Richard J. Sommers, Richmond

Redeemed, The Siege at Petersburg,

Doubleday, 1981

Albert Castel, Decision in the

West, The Atlanta Campaign of 1864,

University Press of Kansas, 1992

Vincent J. Esposito, ed., The West

Point Atlas of American Wars, Frederick

Praeger, Vol 1, 1959

The Seven Days and Atlanta Campaigns Similarities and Differences

- Introduction

The Seven Days' Campaign 1862

Battles for Atlanta 1864

The Comparison

Petersburg/Richmond Campaign 1864

Wargame Representations and Simulations

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 2 no. 1

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.