One constant in both cases concerns the

earlier campaigns that led to these battles. In

both cases, General Joseph E. Johnston had

been maneuvered back to the outskirts of a vital

Confederate city by McClellan and Sherman

respectively. At Richmond he was wounded in

the course of the Battle of Fair Oaks against a

fragment of the Union army that had recently

crossed the Chickahominy River. Before

Atlanta, he was relieved due to President

Davis's fears that he would not fight for that

city, but would be maneuvered out of it as he

had from successive positions over the previous

two months. This time, his replacement as

commanding general came just prior to a battle

similar in plan to Fair Oaks. But the battle

would be fought by Hood.

One constant in both cases concerns the

earlier campaigns that led to these battles. In

both cases, General Joseph E. Johnston had

been maneuvered back to the outskirts of a vital

Confederate city by McClellan and Sherman

respectively. At Richmond he was wounded in

the course of the Battle of Fair Oaks against a

fragment of the Union army that had recently

crossed the Chickahominy River. Before

Atlanta, he was relieved due to President

Davis's fears that he would not fight for that

city, but would be maneuvered out of it as he

had from successive positions over the previous

two months. This time, his replacement as

commanding general came just prior to a battle

similar in plan to Fair Oaks. But the battle

would be fought by Hood.

In both campaigns the Confederate commander, Lee and Hood respectively, had recently assumed command of his army. Lee had about a month, from Johnston's wounding at Fair Oaks, during which McClellan effectively surrendered the initiative. Hood had only two days, though he did have the advantage of having served in the army up to that time. Neither Lee nor Hood were popular choices.

Lee had waged an unsuccessful campaign in West Virginia and was serving as an advisor to Jefferson Davis. He had seniority, so that issue was not a problem. In contrast, Hood was junior to most of the other senior generals in the Army of Tennessee, and his relief of Johnston was viewed unfavorably by many, and particularly by Hardee, perhaps his most important subordinate. Furthermore, there were other senior command changes just prior to both campaigns.

In each case, the command structure was unsettled. As for the opponents, McClellan was conducting his first campaign with the Army of the Potomac, but had been in charge since well before the start of the campaign. Sherman was conducting his first major campaign as an independent army commander, and he too had begun the campaign in that position. Neither had lost or made changes in their senior subordinates.

Neither Confederate general was content to remain on the defensive. Both series of battles feature several attacks, generally frontal, on a portion of the Union force, which was, overall, superior. Lee had an advantage that McClellan's army was essentially static at the beginning. Hood was trying to hit a target that was constantly moving. The ratio of Lee's force to the Union army facing him was closer than for Hood.

The only battles that were not frontal attacks were Frayser's Farm (somewhat more of a meeting engagement) and the Battle of Atlanta, which at least began with a deep move around the Federal flank. Both, tactically, assumed the character of a Confederate attack. Despite the attackers' intentions to attack only a small part of the Union force, the strength ratio of troops actually engaged seldom showed any superiority. For Lee, at Gaine's Mill, there were enough Confederates to gain a costly victory that set McClellan on the path of retreat. But, it was a very close battle that might easily have ended in defeat. At Atlanta on July 22, Hood managed to have a tactical superiority of numbers engaged, but at a much closer ratio. It was not enough to win the battle.

Why were these attacks so often frontal, and futile?

They were not planned that way. When A.R Hill attacked Porter's 5th Corps at Mechanicsville, Jackson was expected to attack on the flank. But he didn't. The Seven Days saw a succession of similar problems as Lee tried to maneuver to advantage, only to have one commander or another show less energy and initiative than expected. These balky subordinates included particularly Stonewall Jackson, who was late on four occasions, as well as Magruder and Huger.

Similarly, Hood's battles at Atlanta showed slow execution and lack of coordination. In both cases the maneuver being attempted, as envisioned by both Lee and Hood, was perhaps beyond the ability of their troops, subordinate commanders, and command structures.

Much is made of the fact threat Hood did not command in person at the front where critical events were unfolding. He was not present in person at Peachtree Creek or Ezra Church. On the 22nd, he was in the city with Cheatham, but it was the critical flank move where things went awry. Hood's mobility was limited by his wounds. The same issue has been raised concerning Spring Hill much later. But Lee did not conduct the Seven Days from the front either. An army commander simply cannot always be in the right place, especially when large-scale maneuver is being attempted. If the commander is away from headquarters with a part of his force, he is that much further removed from the rest of it.

The cost of these frontal attacks can be read in the numbers above. Lee lost about 10,000 more men than did McClellan, from a smaller army. Hood lost similarly. Yet, Lee's campaign is regarded as a success, Hood's as failure. The difference may lie more in the character of their opponents, as well as the fact that Lee in fact had one genuine victory among his series of expensive attacks. McClellan chose retreat. This was partially due to his belief that Lee had the superior numbers. Sherman did not; he had fairly accurate intelligence on relative strengths. However, his progress was checked for a period.

It was not until September I that he managed to get astride Hood's communications at Jonesboro, forcing the abandonment of Atlanta. In contrast, he had gone from Chattanooga to the Chattahoochee in a similar period while Johnston was in command.

One other point of similarity is worth noting, though it goes beyond this campaign. Malvern Hill was perhaps Lee's worst moment. It came immediately after Lee experienced the frustration of failing to trap McClellan's army at Frayser's Farm, due to lack of vigor on the part of his subordinates. He was angry as well. He then launched the Battle of Malvern Hill, an attack with insufficient reconnaissance into massed artillery, in which his army lost heavily while accomplishing little.

The comparison to Spring Hill and Franklin is striking. Hood, pursuing Schofield toward Nashville, came very close to success, but was frustrated by what he saw as lack of energy on the part of subordinates. The terrible frontal assault at Franklin immediately followed, with Hood's frustration the obvious reason for the catastrophic choice of tactics. Lee's loss at Malvern Hill, which resulted in greater losses, is less notable in degree of catastrophe only due to failure of subordinates (notably Huger) to carry out even a frontal assault with the vigor expected, the fact that space did not permit him to employ his whole army in strength. Lee's subsequent accomplishments eclipsed this disaster. Picketts Charge is better known. Consideration of Hood will always remember Franklin.

So, why should we care, even if there are many similarities between these campaigns?

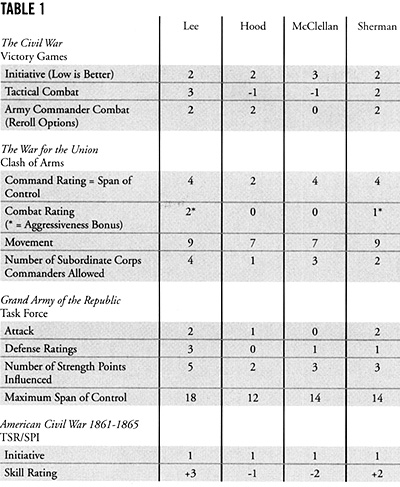

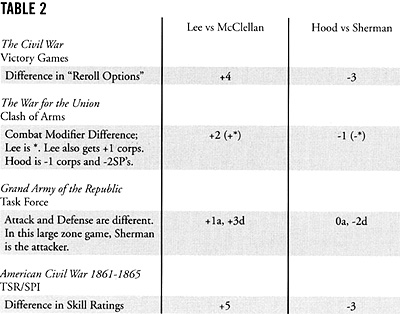

As those interested in Military history, and the potential to reexamine these moments in war games, the issue of leadership and ability ratings perhaps excites the keenest interest. In campaign games treating the whole war, Lee generally has the best rating. Hood (as an army leader) isn't at the bottom, thanks to the likes of Butler, but he's not far away.

Four examples are:

Four examples are:

I have argued that the results in both campaigns were not that different. In fact, Lee had the advantage of a more favorable ratio of forces, and a longer time in command before his first battle. Yet, in game terms, the numbers assigned to these individuals are remarkably different, as are their general reputations. This has much to do with what happened later.

Hood had the misfortune to assume command as the Confederacy's fortunes were fading. Lee assumed command when both the Confederacy's resources were higher and the less capable enemy commanders had not yet been relegated to other duties. While I would certainly not argue that Hood was Lee's equal, this is evident more in later events than in the course of these two campaigns.

There is another issue. We have gotten used to the idea that a significant sized city, especially one defended by fortifications, gives the defender an advantage. This is pervasive in the rules of virtually all war games. Yet here, the Confederacy defended both of these cities, and did so at a much greater cost to themselves than to the Union, which in a strategic sense was the attacker. Are there counterexamples, where the defender did get the expected advantage? New Orleans fell to the Navy. Nashville fell without a fight in 1862, as did Memphis, as a result of distant maneuver.

Vicksburg might be considered as a strategic and fortified city. In contrast to the campaigns for Atlanta and Richmond, at Vicksburg Pemberton did not employ an aggressive defense. Indeed, his response was rather passive. Grant did the attacking, losing 2441 at Champion Hill and 3199 in the assault on Vicksburg itself out of an army of about 33,000 and 45,000 respectively. Pemberton lost 3851 of about 20,000 at Champion Hill, more heavily than Grant, and probably rather lightly in Grant's later assault, but at the end of the siege surrendered about 30,000. (Livermore does not list losses for Big Black River, and other minor engagements of the campaign.) This one example of a less aggressive defense was decidedly unsuccessful.

No other major city except Richmond itself, in 1864-1865, was the object of such a contest between major armies. If cities are to give a defensive advantage, a game system also needs to convey the negatives such as the tactical restrictions of having to defend it, and the political pressure to force the enemy away from it. Johnston, in 1864, was unwilling to acknowledge these negatives, and so lost the confidence of his commander in chief, and his command.

This raises an interesting issue.

This raises an interesting issue.

How does the contest for Richmond in 1864 differ from these other two campaigns?

It was a successful defense, and not at a cost as dear (relative to the Union losses) as Richmond in 1862 or Atlanta 1864.

An examination of that campaign reveals a similarity of tactics. Lee held fortifications, but also used part of his army to strike at the enemy as he maneuvered on the flanks. Unlike 1862, Lee was no more successful at driving Grant away from Richmond and Petersburg than Hood was driving Sherman away from Atlanta. A series of battles was fought below Petersburg (Weldon RR in August, Poplar Spring Church in September-Oct, and Boydron Plank Road in October) in which A.P. Hill delivered attacks with some success, checking but not rolling back the lengthening siege lines.

Also unlike the earlier cases, Grant made a number of costly assaults, as did Lee, which were more frontal in character. A key difference is this: Lee had been in command for two years, and A. P. Hill as well as Ewell and many other subordinates had been with him all of that time.

The Seven Days and Atlanta Campaigns Similarities and Differences

- Introduction

The Seven Days' Campaign 1862

Battles for Atlanta 1864

The Comparison

Petersburg/Richmond Campaign 1864

Wargame Representations and Simulations

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 2 no. 1

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.