The Marine Defense Battalions were born of two disparate influences:

the traditional Marine Corps mission of defending advanced Navy bases and

a Congress interested in funding only "defensive" units. Initially, the

Defense Battalion was composed of 450 men armed with the weapons which

would remain standard through the unit's evolution: 5" naval guns, 3" anti-aircraft weapons, machine guns, and searchlights.

The Marine Defense Battalions were born of two disparate influences:

the traditional Marine Corps mission of defending advanced Navy bases and

a Congress interested in funding only "defensive" units. Initially, the

Defense Battalion was composed of 450 men armed with the weapons which

would remain standard through the unit's evolution: 5" naval guns, 3" anti-aircraft weapons, machine guns, and searchlights.

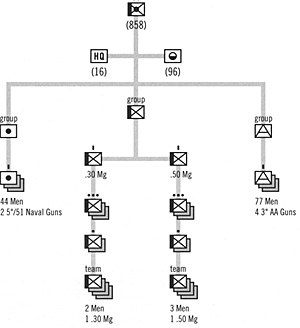

After surveying the most likely spots where the Battalions would be deployed -- Midway, Wake and Johnston islands in the Pacific -- it became obvious that 450 men fell far short of the requirements for an effective defense. As a result, the order of battle was increased in the summer of 1939 to 800+ men with the weapons shown in the diagram.

Seven Defense Battalions were organized before the attack on Pearl Harbor, and all but two were serving in the Pacific on December 7th. The battalions were never rigidly standardized, however, and the actual number of men and guns depended upon the nature of the spot to be defended. The Battalions were intended to keep the enemy off the beaches through massed firepower, using their five-inch guns to take on any light naval forces or transports, and defending the beaches with 3" anti-aircraft and machine-guns. The trouble is, none of these weapons were mobile, and they had no infantry to back them up. If the enemy did manage to get past the beach, there was no one left to contain the attack.

The Marines recognized that the battalions had their limitations. As they put it, the units had "sufficient strength to repel ... raids by small landing parties," but not enough to fend off a full scale invasion. In the end, Wake proved them right, even though the garrison was successfiil against the first Japanese attempt. Despite this, the Marine Corps continued to mobilize Defense Battalions up until the end of 1943. By then, there were 20, but as it became obvious that the Japanese would never be able to retake the ground they had lost, the Battalions were either phased out or converted to anti-aircraft units.

"SEND US MORE JAPS"

As the one bright spot in a torrent of gloomy news, the American press seized on Wake as a rallying cry for the country. Newspaper readers were urged to "remember Wake," equally with Pearl Harbor. Radio sang the praises of Wake's "gallant defenders," and the Marines heard more than they cared for of this constant propagandizing while they searched for a little entertainment on their short wave sets. The crowning achievement of Wake hype, however, came about midway through the second week of the ordeal. The radio declared that the defenders of Wake had turned down any help from Pearl, requesting instead that headquarters "Send us more Japs!" This comment raised the art of Marine malediction on Wake to new heights.

Years later it was discovered that the press had fallen for one of code clerk Bernard Lauff's private jokes with the code staff back at Pearl. It was American practice at the time to lead and follow each message with gibberish in order to confuse enemy decoding attempts. On the day that the first invasion was thwarted, Lauff preceded Cunningham's report to Pearl with this inadvertent ticket to the propaganda hall of fame:

- SEND US STOP NOW IS THE TIME FOR ALL GOOD MEN

TO COME TO THE AID OF THEIR PARTY STOP CUNNINGHAM MORE JAPS

If Lauff had known what was going to happen to his little gem, he might have included his fellow Marine's opinion on it: "anyone who wants my share of Japs can have it."

After the fall of Wake, Japanese interrogators grilled Wake's naval commander about the "send more Japs" line. After repeated denials, they conceded that "it was damned good propaganda, anyhow."

With their stumpy forelegs and high haunches, the rats of Wake looked strange, and acted stranger. For hundreds of years they hadn't had a single enemy worth speaking of, and so they treated the Marines as extra- large versions of themselves. One of their favorite activities was to scamper into foxholes to cuddle up with sleeping Marines. The leathernecks would wake up in the middle of the night with dozens of the creatures curled up on top of them.

Gunnery Sergeant Raymon Cragg was undoubtedly, if briefly, the most popular Marine on Wake according to the rats. Cragg took exceptionally good care of his feet, liberally applying foot powder after every nightly bath in Wake's lagoon. The night came, however, when Sergeant Cragg had no more foot powder, so he stumbled through the dark to where he could scrounge some. Satisfied that his feet were now secure, Cragg felt his way back to his foxhole and went to sleep. He woke after a brief snooze to find hundreds of rats crawling all over his boots, and it was then that the good Sergeant realized that he had coated his feet with powdered cheese.

Occasionally, the rats exceeded their status as a benign nuisance. After one particularly severe bombing raid, a rat who was sharing a foxhole with one unfortunate Marine had a spectacular nervous breakdown, running high speed circles inside the foxhole and finishing off by clamping his teeth into the Marine's nose. To the great amusement of his fellow leathernecks, the afflicted Marine had to club the animal to death before it would let go.

Wake's civilian volunteers had a lot to learn about modern warfare, particularly the aerial aspects. As the Marines raced to their guns on December 8th, one civilian pointed to the first salvo of falling bombs and shouted "look, their wheels are falling off!" Another enterprising soul trucked an unexploded bomb to Cunningham's headquarters: "hey, captain, I found a dud. You want me to disarm it?" Backing away at fill speed, Cunningham ordered him to drop it in the lagoon. Both civilian and truck and survived the experience.

Some of the Marines had a bit to learn, too. Sergeant Cragg of the foot powder episode was dashing for his air raid shelter when he was suddenly yanked backward and dropped flat on the ground. It seems that the sergeant had forgotten to take off his earphone set on the way to the dugout. The dugout was thirty feet away. The telephone cord, twenty feet long. Cragg survived the raid without a scratch, only to endure a perpetual ribbing from his crew; "did the sergeant hurt himself?," chided one emerging private.

In accounts of orders and casualties and desperate last stands, it's easy to lose sight of the fact that the Marines were human beings, and very young human beings, at that. They didn't spend what little free time they had dreaming up brave sound bites like "Send Us More Japs!" They were far too tired for that.

Rather, as Major Devereaux once wrote, they spent most of their off-duty time "grousing about their lot and talking about blondes." While it may not have been the steely-eyed determination of John Wayne movies, the continued ability of the Marines to laugh at the situation and each other, convinced Devereaux that morale was not going to be one of his problems on Wake.

America's Forlorn Hope US Marines Defend Wake Island: Dec 8-23, 1941

- Introduction

First Attack: Air Raid

IJN Invasion Repulsed

IJN Invasion: Round Two

Surrender and Bibliography

Map: Wake Island

VMF-211

US Marines Defense Battalion

Imperial Japanese Special Naval Landing Force

Back to Table of Contents -- Against the Odds vol. 1 no. 2

Back to Against the Odds List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by LPS.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

* Buy this back issue or subscribe to Against the Odds direct from LPS.