Wagram

Two years later Napoleon was again at war with Austria, and in the campaign of Eckmuhl had given the world another magnificent example of what his genius could effect. Vienna fell an easy prey to him, and shortly after its capture he began to cast about for a means of getting at the Archduke Charles, who had made his escape to the Northern bank of the Danube, and whose army formed a standing menace and nucleus of resistance to the French power.

Two years later Napoleon was again at war with Austria, and in the campaign of Eckmuhl had given the world another magnificent example of what his genius could effect. Vienna fell an easy prey to him, and shortly after its capture he began to cast about for a means of getting at the Archduke Charles, who had made his escape to the Northern bank of the Danube, and whose army formed a standing menace and nucleus of resistance to the French power.

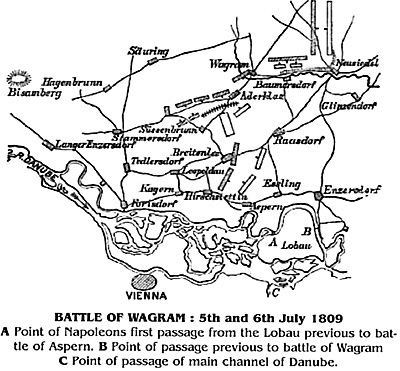

Battle of Wagram: 5th and 6th July 1809: A: Point of Napoleon's first passage from the Lobau previous to battle of Aspern. B: Point of passage previous to battle of Wagram. C: Point of passage of main channel of Danube.

On the 21st and 22nd of May, 1809, Napoleon had endeavoured to force his way across a broad river in the presence of a powerful enemy, relying on one frail bridge only. It says much for the skill and bravery of the French troops that they so nearly achieved success as they did, and that the breaking of their bridge alone held them off from victory. As it was, however, they were driven back into the Lobau, and narrowly escaped total destruction. But Napoleon showed himself greater in disaster and more fertile in resource than even he was in the flush of conquest. He collected a powerful army in the strong entrenched camp which the island formed, and at the commencement of July was ready to make another effort.

In order to deceive his antagonist, for weeks past he had been preparing batteries (opposite the place marked A. on the plan), where he had originally crossed, and the spoils of the Arsenal of Vienna placed a large number of powerful guns at his disposal, with which he hastened to arm his works. More than 100 heavy pieces, therefore, bristled along the northern shore of the island. It is necessary to note the existence and position of these guns, for they will play an important part in the great battle which we are going to deal with.

On the night of the 4th of July a furious cannonade from these batteries entirely deceived his adversaries, while the whole French army slipped across from the eastern side of the island in front of Enzersdorf, and on the morning of the 5th the Austrians found their left completely turned, all their elaborate preparations between Aspern and Essling rendered useless, and their enemy in superior numbers across the Danube and preparing to sweep round their left flank. They fell slowly back to the Wagram plateau, and the evening found them drawn on a vast arc, stretching from Neusiedel, by Wagram and Safiring, to Hagenbrunn. The Emperor that evening tried to force their line between Wagram, and Baumersdorf, but his effort was repulsed. Early next morning he had intended to renew the attack, but the Archduke was beforehand with him, and assailed his right at Glinzendorf ere he could move.

The battle which now ensued is one in which the incidents succeed one another with bewildering rapidiEy, and fortune appears to favour both sides alternately throughoot the day. While the French were winning at one end of their long line they were being beaten at another, and when victory seemed more than once within grasp of the Austrians, their chance appeared suddenly to melt away. As we regard the combat from the artillerist's point of view alone, we can only take a very brief survey of its incidents, but one or two features stand out distinctly and must not be passed over.

In the first place this is one of the greatest fights, measured by the numbers engaged, which has ever taken place. The French force has been differently stated by various authors, but was probably not less than 150,000 infantry, 30,000 cavalry, and 600 field guns. The Austrians were considerably weaker in number, and mustered perhaps 140,000 men, but were supported by a very powerful artillery, too.

Then, again, on this day an unexampled use was made of guns, and Marbot says in his Memoirs that at the commencement of the fight on the 6th, 1200 pieces were in action on both sides, and that such a tremendous artillery combat had never before been witnessed. Finally, the fact that these vast hosts were locked in a death struggle within sight of the towers and steeples of Vienna, from which the straining eyes of the inhabitants watched with painful interest the lines of smoke, gives a dramatic air to the combat, such as none other save perhaps Waterloo possesses.

The Austrian attack on his right took Napoleon, who was near Raasdorf with the guard and reserve cavalry, by surprise, but he hurried up his guard and a strong force of artillery to support Davout, whose corps was on the threatened flank, and the Austrians were brought to a stand-still principally, Marbot says, by the fire of these guns. Hardly, however, was the danger over on his right ere Napoleon's attention was rudely drawn to his centre and left.

He had intended to commence the fight on the 6th by assailing the Austrian centre and left. Massena had been brought, therefore, from Aspern towards Aderklaa, and the corps of Oudinot, Eugene, Bernadotte, and Marmont were all drawn up between Davout, on the extreme right, and that village. Thus the French left had been unduly weakened.

While the Austrian left were pressing forward at Glinzendorf, Bellegarde in their centre also advanced to Aderklaa, and pushed Bernadotte roughly out of the village. Klenau and Kollowrath, on the Austrian right, likewise took the offensive towards Breitenlee and Aspern, and were soon threatening the French flank and rear in a very dangerous manner at the spot where the removal of Massena rendered their line particularly weak.

Meanwhile that Marshal had sent one of his divisions, under St. Cyr, against Aderklaa, and the Frenchmen, penetrating rashly beyond it, and getting somewhat out of hand, had come under a heavy artillery fire from near Wagram, had been charged in flank by the Austrian cavalry and, becoming demoralised, had broken and fallen back in confusion to the village. The Archduke eagerly availed himself of the opportunity thus offered him, headed his troops in person, and so vigorously followed up the success that he drove his assailants, not only out of the village, but some distance beyond it.

Napoleon aiming a gun of the Horse Artillery of the Imperial Guard. (JOB)

The part played here by these guns was of the first importance, and affords an excellent illustration of the power of the arm on the defensive, although later on as we shall see, how they were to be thrown into the scale again with even more marked effect in the attack.

Perceiving that the moment was not yet ripe for his great blow, Napoleon sent Massena to stem the Austrian inroad on his left, while Davout was ordered to turn the enemy's flank at Neusiedel. The Austrian right meanwhile had also, however, to experience the power of artillery, for in their brilliant advance near the river they had exposed their right to the fire of the heavy artillery which, as has already been stated, Napoleon had placed in the Lobau.

The flanking fire of these guns materially checked the enemy's progress, and, combined with the efforts of Massena, brought him to a stand-still. Meanwhile Napoleon rode up and down the fire-swept angle of his line near Aderkiaa, and ever and again cast an anxious eye at the tower of Neusiedel which juts out from the plateau of Wagram away to the east. He had determined to wait for the success of Davout's turning movement ere he delivered his great attack on the enemy's centre, and all now depended on the hero of Auerstadt.

The various accounts all agree in praising the coolness and presence of mind displayed by Napoleon at this juncture. The sound of the cannon in their rear near the Danube, had disquieted the minds of soldiers and staff officers alike, and, unable to fathom the Emperor's intentions, they kept drawing his notice to what appeared to them a most critical situation. He rode up and down in silence, and paid but little attention to the murmurs and remarks that began to be heard about him. Massena, having gained an advantage over the Austrian right with the help of the artillery from the Lobau, sent Marbot, as he tells us in his Memoirs, to beg the Emperor to let him make a counter attack. But the Emperor, intent on watching for a sign of Davout's progress, paid no attention to the message.

Suddenly he was all animation. The smoke of Davout's guns had clearly rolled beyond the tower of Neusiedel. He turned to Marbot. " Go, tell Massena to fall on everything before him, and the battle is won!" Then he called to Lauriston, "Take 100 guns, 60 of which will be from my guard, and go and crush the enemy!"

The great stroke he had been meditating all day was now to fall. This great battery first shattered the enemy with a heavy fire, then Bessieres charged to the front with six regiments of Currassiers, and, supported by the cavalry, the huge column, celebrated in military history for its immense size, led by MacDonald, was driven through the Austrian centre, and Davout having rolled up his left, the Archduke was compelled to order a general retreat. Although beaten, the Austrians however were by no means demoralised, and but very few trophies fell into the hands of the conquerers. Indeed, on the Archduke's statue in Vienna "Wagram" is emblazoned as a victory beside "Aspern".

That the Emperor did not energetically follow up his success has been variously explained. Some say he was ill, and not, therefore, as energetic as usual. He himself blamed his cavalry. Bessieres was wounded, and Lasalle, the brilliant cavalry soldier, was dead, and therefore, perhaps, the arm was not handled as it otherwise might have been.

But one excellent reason for the Austrians' escape from graver disaster than they experienced is to be found in the action of the splendid body of their artillery which always remained intact, and which covered their retreat with a stubborn courage that cannot be too highly praised.

Indeed, Wagram is exceptionally rich in examples of what artillery can achieve. We have the great opening cannonade on the second day; the ready manner in which it assisted in parrying the first Austrian blow on the French right, and then the concentration of the great battery to close the breach at the French centre.

The victorious Austrian right is next brought to a standstill by the guns in the Lobau, and, finally, the great mass of artillery, against which the Austrian advance in the centre has been shattered, is used by the Emperor when the moment is ripe to open the way for the decisive stroke, long in contemplation, which is to decide, the battle. And if the value of artillery in the attack is thus well exemplified, its even nobler role in stemming the torrent of pursuit is illustrated also in the generous self-sacrifice displayed by the Austrian gunners when their army was compelled to retire .

That the result of this battle was not more decisive has been variously accounted for. The cavalry blamed by Napoleon, and Taubert thinks that the artillery blow at the close of the battle was less effective than that of Friedland because the mass of guns was unwieldy, the mobility of the foot artillery inadequate, and the advance of the guns premature. To us it seems, however, that the effective fire of the Austrian guns had a predominating effect in staving off complete disaster. Fifteen French guns were dismounted by them as they moved into position for the final effort, and their conduct during the retreat has already been alluded to. The truth appears also to be that the quality of the French infantry had fallen off. As the continual warfare depleted the sources from which it was drawn, younger and physically inferior conscripts had to be accepted, and there was less time to train them than formerly.

Therefore, dense unwieldy masses, such as MacDonald's column, were, in the latter years of the empire, substituted for the lighter formations of Austerlitz and Jena, and, unless the foe were demoralised, which the Austrians were not, such vast bodies must suffer enormously in the attack. Moreover, the Austrians, since their victory at Aspern, had ceased to regard these great French columns with the same dread they had once felt for them, and the effect of such crowded masses was at all times chiefly moral. These various causes will probably more truly account for the absence of trophies than any defects in the handling of the artillery, to whom, on the contrary, such success as crowned the day may in a large measure be traced.

Henceforth we shall find Napoleon relying more and more on his artillery, and as the inferior quality of the infantry demanded increased support, the proportion of guns with his armies steadily grew.

At Borodino he brought an immense battery of guns to bear on the Russian centre, but beyond the fact that it may serve as an illustration of the effective manner of handling the arm, the action of the artillery in this battle can hardly be regarded in the light of a brilliant achievement.

Napoleon marked what had happened from a distance, and with quick decision hastened to retrieve the disaster. He hurried Druot forward with four Horse artillery batteries of the guard to check the forward rush of the enemy, the remaining six Field Batteries followed as fast as they could, and soon a great line of about 100 guns was drawn across the breech in the French line and held the enemy at bay. [4]

Napoleon marked what had happened from a distance, and with quick decision hastened to retrieve the disaster. He hurried Druot forward with four Horse artillery batteries of the guard to check the forward rush of the enemy, the remaining six Field Batteries followed as fast as they could, and soon a great line of about 100 guns was drawn across the breech in the French line and held the enemy at bay. [4]

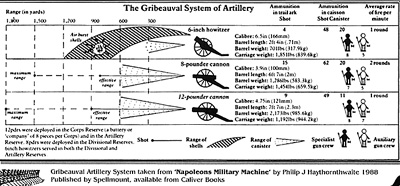

Jumbo Illustration Gribeauval System of Artillery (slow: 113K)

Notes

[1] The use of Field Artillery on service.

Achievements of Field Artillery The Era of Napoleon: Part 1

Achievements of Field Artillery The Era of Napoleon: Part 2

[2] Taubert, however, places the Russian

strength as high as 60,000 on the left bank of the river.

[3] In a letter to his brother, dated "Tilset,

June 26th, 1807," which is given by Captain de l'Ain in his account of this battle,

Senarmont says "The position of the enemy showed 4000 dead on this spot

alone " (that opposite to his battery) "I lost the chief of my staff Colonel Formo, killed

by a ball at the end of the action; I have had 3 officers and 62 gunners placed hors de

combat, and a charming horse wounded under me; I fear I shall not be able to

save him."

[4] Jomini, in his "Precis de l'art de la

guerre," says "Cependant on a vu, a Wagram, Napoleon jeter une batterie de 100 pieces

dans la trouee occasionnee a sa ligne pars le depart du corps de Massena,

et contenir ainsi tout l'effort du centre des Autrichiens; mais il serait bien difficile d'eriger

en maxime un pareil emploi de l'artillerie." In spite of the dictum of the great strategist,

however, we shall, in the campaign of 1870, find the example set at Wagrarn

successfully repeated on more than one occasion.

Back to Age of Napoleon 29 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com