Maj. May was professor of military topography at the Royal Military Academy. Though some of the text is now slightly dated, we present here the first part of the Napoleonic section of his work on the history of the tactical use of artillery.

With the advent of the Nineteenth Century the position of artillery as an arm became immensely improved, and the divisional system of organization introduced by the young French Republic was to a large degree responsible for the change. Mobility and flexibility were the characteristic of their armies, and their guns having to keep pace with the other arms, increases and successful efforts were made to render them equal to the new demands.

With the advent of the Nineteenth Century the position of artillery as an arm became immensely improved, and the divisional system of organization introduced by the young French Republic was to a large degree responsible for the change. Mobility and flexibility were the characteristic of their armies, and their guns having to keep pace with the other arms, increases and successful efforts were made to render them equal to the new demands.

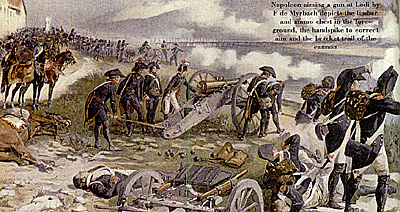

Napoleon aiming a gun at Lodi.

Not only this, but the necessities of the Republic obliged it to adopt a different method of conducting operations to what was in vogue with States better endowed in all the paraphernalia and equipment required by the old methodical system of fighting. Armies were split up into units, each complete in itself, able to move independently, and, above all, able to forage for themselves.

The pedantic and formal methods which looked for supply from magazines and depots, and regarded the safety of communications as a first consideration, were gradually swept away, and with them many of the old traditions and prejudices which had crystalized round them. Battalion guns disappeared with the rest, and artillery assumed its proper place, looking to a chief of its own for direction, and forming an integral portion of an army on an equal footing with the other arms.

As we have hinted already, even Frederick had viewed artillery, at the commencement of his career at any rate, with more suspicion than regard, and probably to the end of his life looked upon the arm rather as a necessary evil than a gift of providence.

As we have hinted already, even Frederick had viewed artillery, at the commencement of his career at any rate, with more suspicion than regard, and probably to the end of his life looked upon the arm rather as a necessary evil than a gift of providence.

Large Illustration 1808 French Horse Artillery (very slow: 210K)

In the early days of Napoleon, although as an artillery officer he naturally appreciated its powers, economical considerations equipped him but sparcely with artillery, and probably hampered its action in his hands. Artillerymen cannot be trained in a hurry, nor are losses of guns and horses easily replaced.

As, however, he grew in power, until eventually the whole resources of the State were at his disposal, such considerations no longer restrained the full exercise of his judgement, and the General who set so high a store on fire elect, was not slow to develop the arm which offered the richest result in that respect.

To quote his own words "C'est l'artillerie de ma garde qui decide la plupart des batailles, parce que l'ayaut tonjours sous la main, Je puis la porter partout ou il est necessaire." It must be noted, however, that these words were not intended to imply that because a mass of guns were held in hand they remained idle until the supreme moment arrived. On the contrary, at Wagram we find them, as we shall see later on, actively engaged during the whole contest, and filling a breech in his own line as well as making one in that of his foes. The heresy of a reserve of artillery was never encouraged by Napoleon, although he took care to have a powerful force ever close to him "sous la main."

To quote his own words "C'est l'artillerie de ma garde qui decide la plupart des batailles, parce que l'ayaut tonjours sous la main, Je puis la porter partout ou il est necessaire." It must be noted, however, that these words were not intended to imply that because a mass of guns were held in hand they remained idle until the supreme moment arrived. On the contrary, at Wagram we find them, as we shall see later on, actively engaged during the whole contest, and filling a breech in his own line as well as making one in that of his foes. The heresy of a reserve of artillery was never encouraged by Napoleon, although he took care to have a powerful force ever close to him "sous la main."

The bringing up of the artillery of the guard, a force which soon became invested with special terror in the eyes of his foes, to strike the final blow is indeed a marked feature in his later battles, but it was not till after the tactics of the arrn had been carefullv revised at the great camp of Boulogne in 1805, that we find any striking examples of its employment in that concentrated fashion which is essential to decisive results. At Marengo, however, that fortunate victory which made him first consul, he owed much to the unexpected appearance on the scene of twelve pieces of Boudet's division, and the, French army was, indebted for its salvation not a little to their support.

Napoleon, however, had yet to learn the full power of a mass of guns in the bitter school of experience, and it is from his most stubborn foes that the first example of the effect of a great mass of guns may be quoted.

Achievements of Field Artillery The Era of Napoleon: Part 1

Achievements of Field Artillery The Era of Napoleon: Part 2

Taubert says of this battle: "The twelve guns of Boudet's division, which had only just arrived, checked the victorious career of the Austrians by their unexpected and effective fire; they became, too, the supporting point of all the manoeuvres which turned

the fate of the action. It was the last barrier of the already beaten

French army; by it the French Commander-in-Chief supported

his discomfited and exhausted divisions; and from it and the impetuous

attack of fresh forces, resulted the change which snatched the

blood-bought victory from the Austrians." [1]

Taubert says of this battle: "The twelve guns of Boudet's division, which had only just arrived, checked the victorious career of the Austrians by their unexpected and effective fire; they became, too, the supporting point of all the manoeuvres which turned

the fate of the action. It was the last barrier of the already beaten

French army; by it the French Commander-in-Chief supported

his discomfited and exhausted divisions; and from it and the impetuous

attack of fresh forces, resulted the change which snatched the

blood-bought victory from the Austrians." [1]

Back to Age of Napoleon 29 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com