It is remarkable that the Russian army has ever been especially strong in artillery, and has always attached great importance to the arm. Just as Frederick felt the weight of Russian batteries at Kunersdorf, so did the next great military genius who arose after him experience their power at Eylau.

It is remarkable that the Russian army has ever been especially strong in artillery, and has always attached great importance to the arm. Just as Frederick felt the weight of Russian batteries at Kunersdorf, so did the next great military genius who arose after him experience their power at Eylau.

Eylau 1807 in the background (centre right) can be seen the firing line of French guns in a 'mass battery (Swebach)

The feat of the great Russian battery of 40 guns, which at this bloody battle destroyed the corps of Augereau, is justly celebrated in the annals of war, and if we do not here dwell at any great length upon it, it is not because We would depreciate in the least the deeds of the Russian gunners, but rather because the peculiar conditions under which their triumph was effected take it a little out of the realm of legitimately earned success, and stamp it rather with the character of a brilliant coup rendered possible, or at least greatly assisted, by fortuitous and exceptional circumstances.

Eylau

Napoleon, finding the Russians standing firm at Preussisch Eylau on the 7th February, 1807, determined to turn their left. The better to conceal his intentions he commenced a violent attack on their right and centre soon after daylight. The left, under Augereau, advanced in heavy columns towards Schloditten, whilst Soult's corps preceded by 150 pieces of artillery pushed on against the centre.

The Russians had distributed a very powerful force of artillery along their front, and Augereau's corps soon found itself opposite to a mass of about 70 guns. These ploughed his crowded columns with most deadly effect, and they recoiled under the fire to the left in order to gain what protection they might from the shelter of a detached house which stood before them. At the same moment a dense storm of snow came on, and soon neither side could see their opponents.

Moreover, the melting snow so wetted the muskets and ammunition that they became almost useless, and the infantry on both sides were incapable of fire action.

In the midst of the confusion thus engendered, and still much shaken by the unremitting artillery fire, Augereau's column found itself assailed in the obscurity by the Russian reserve cavalry on one side and by their right wing on the other. Prevented by the cavalry from deploying, unable to use their weapons, and blinded by the snow, the French columns became almost helpless, and were literally torn to pieces by the battery before them. The whole of Augereau's corps which went into action, more than 16,000 strong was destroyed, save a wretched remnant of 1500 men that managed to crawl back to the French position. The remainder were all either taken or left on the field, and Augereau himself, with his two Generals of division, Desgardens and lieudelet, was desperately wounded.

This immense effect has caused the feat of the Russian guns to be justly celebrated, and as an example of what, under favourable conditions, a mass of guns can accomplish, it certainly deserves to be remembered. Napoleon himself is said to have been profoundly impressed by what he saw, and the terrible loss he sustained forcibly brought home to him the tremendous power a concentrated artillery can develop. The chapter of accidents, however, which prevented the French infantry from availing themselves of their most valuable weapon, and the manner in which the snowstorm favoured the guns seems to detract somewhat from the feat they accomplished, and artillery has scored triumphs where the field was fair, and neither side was favoured by fortune upon which we would rather build its reputation.

This instance, therefore, of its power, although a feat of arms of which the arm may be justly proud, is but lightly touched upon here, and we pass on to another which soon followed it, which perhaps astonished the great Emperor even more, and which is more proudly remembered by gunners because on that occasion artillery, with noble unselfishness, entered the lists with all the odds against it, and dared destruction to come to the rescue of its hard pressed comrades of the other arms.

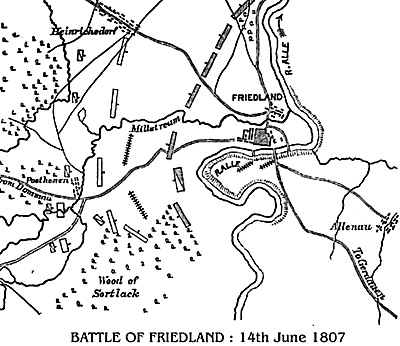

Friedland

Senarmont's "bouquet de feu" at Friedland was achieved with an audacity so brilliant as to approach temerity, and had he not snatched success from the struggle, the feat would no doubt have been termed impossible. Let us see how his valour was justified:

Senarmont's "bouquet de feu" at Friedland was achieved with an audacity so brilliant as to approach temerity, and had he not snatched success from the struggle, the feat would no doubt have been termed impossible. Let us see how his valour was justified:

General Senarmont, an enthusiastic artilleryman, had been appointed on the 21st of February, 1807, immediately, therefore, after the battle we have just been speaking of, to the command of the artillery of the 1st Corps of Napoleon's army. This corps was under the command of Bernadotte, Prince of Fonte Corvo, and consisted of three divisions under Generals Dupont, Lapisse, and Villatte. The guns placed under his orders numbered 38 pieces in all: that is to say, 4 12prs., 22 6-prs, 4 4-prs., and 8 7-pr. howitzers. Of these, 12 were allotted to Dupont's division, and 10 to each of the other two divisions. Six pieces were held in hand to form an artillery reserve for the corps.

Both sides were so exhausted by the bloody and indecisive battle of Eylau, that neither seemed in any hurry to recommence hostilities, and for more than three months not a blow was struck. On the 5th of June, however, a combat took place at Spandau, in which Bernadotte was wounded, and the command of the 1st Corps devolved on Victor in consequence.

On the 14th of June the Russian General, Beningsen, thought he saw an opportunity to crush the corps of Lannes, which appeared temptingly unsupported in front of him, ere Napoleon could come to its assistance, and, accordingly, early that morning he crossed the Alle at Friedland to crush an opponent who seemed at his mercy.

The intended victim skilfully kept his adversary at bay however, and his force being gradually reinforced from the rear, the resistance proved far more serious than the Russian General had anticipated. More and more troops were hurried across the river as the combat deepened, and the golden moments were slipping by, and soon the Russian General found himself committed to a general action, fighting with his back to a broad river against an adversary every hour growing stronger.

Napoleon arrived on the scene about 1 o'clock from Dommau, and determined to attack. It was the anniversary of Marengo, and the day was therefore peculiarly auspicious. He viewed his enemy defiling over the bridges on the narrow plain beneath him with an exultating confidence. They were soon drawn up upon the cord of the arc formed by the river here, while a powerful artillery covered their retreat over the bridges from the opposite bank of the river. Lannes and Mortier, who had come to his support, had fallen back to the high ground between Fosthenen and Heinrichsdorf, and in the woods behind Napoleon assembled his forcesas they successively arrived.

By 4 o'clock about 70,000 infantry and 10,000 horse were assembled, according to Alison, while Beningsen had no more than 38,000 infantry, and 8000 cavalry on the left bank of the Alle to oppose them with. [2] His dreams of destroying Lannes had long since vanished, and he realised with dismay that now he could only hope to hold his ground till nightfall, when he might perhaps slip away from his powerful opponent and gain the right bank of the Alle once more.

But Napoleon had marked the importance of Friedland and was not going to let him escape.

At 5 o'clock, a salvo of artillery gave the signal for the French to assume the offensive, and Ney's corps, consisting of the divisions of Bipon and Marchand, emerged from behind Posthenen, and swiftly moved to the attack between the mill stream and the river. Their impetuous leader hurried them on in two columns to outflank: the Russian left, and at first he carried all before him, but the further he pressed forward the more his right column, formed from Marchand's division, became exposed to a raking fire from the powerful Russian batteries on the opposite bank of the Alle. His left column, too, was soon heavily assailed, while the cramped nature of the ground and the small space available for manoeuvre further hampered his movements. Secure from attack, owing to their unique position, the Russian gunners across the river laid with cool precision, and every shot told. Soon Ney's columns were seen to hesitate and waver, and Bragation, who commanded the Russian left, promptly took advantage of their confusion, the Russian Guard charged the confused columns of their opponents resolutely, and in a few minutes not only had the French lost all the ground they had just gained, but the safety of their right wing appeared in jeopardy.

Meanwhile, however, Victor's corps which had been held in reserve was moved forward, and Dupout's division hurried on to retrieve the disaster. General SeDarmont accompanied the battery belonging to this division into action, but found the Russian fire overpoweringly strong, and the French infantry could make no headway against the tide of Russian success. The moment was a critical one, and some great effort must be made if the fortunes of the day were to be changed. Senarmont saw a great opportunity for his arm, and having obtained the consent of Victor to utilise all the guns of his Corps as he pleased, he swiftly put his project into execution.

In spite of the remonstrances of the different Generals, who naturally did not wish to be deprived of all their artillery at such a moment, he formed the Divisional Artillery of the corps into two great batteries of fifteen guns each, with the remainder in reserve, and placed one on the right in front of the wood of Sortlack, and the other on the left in advance of Posthenen, behind which he posted the reserve.

Thus, the enemy's guns and columns as they pressed forward were brought under a concentrated crossfire, which almost immediately began to tell. As the Russians fell back before the advance of the French reinforcements and this well directed fire, the two great batteries moved forward, and soon from the converging nature of their movements they approached close to one another, and were formed together into one great battery, which Senarmont could himself direct with more facility, than when he had to move, as he did, from one battery to another.

The guns had opened at 400 metres, but after five or six salvoes they were led with rare audacity within half that distance of the enemy. As the guns pushed on beyond the French line all who saw them were absolutely astounded, and it is said that Napoleon himself was at first so greatly taken aback that he cried in horror, "Mon Dieu! le General Senarmont deserte!"

Then he sent his aide-de-camp, Mouton, to call the eager General back from his rash enterprise, and to ask him what he meant by thus pushing forward unsupported. Full of his project, Senarmont would listen to no one however. "Laissez moi faire avec mes cannoniers," he shouted, " Je responde de tout."

Little pleased with the message he had to bear, Mouton returned to the Emperor. But already the keen eye of the latter had seen that the guns were producing an effect, and the success of his lieutenant had atoned already for his independence. Mouton found him quite mollified and a pleased smile played round his mouth as he received him. He shrugged his shoulders and said laughingly, "These gunners are unruly fellows, let them do as they will".

The well-served fire of this great mass of guns had in fact relieved the pressure on the French right at once, and drew the shells of the Russian batteries from off the infantry. Gathering way once more under their support, Dupont's division returned to the charge, and soon Ney was assailing the town of Friedland, and the Russian line of retreat across the bridges was dangerously threatened. As the French pushed on, the press and confusion in the town became so obvious that their divisions were hurried forward to the assault, the streets were forced, and many buildings, and the bridges were soon in flames. The defeat of the Russian left meanwhile had dangerously exposed their centre, and Beningsen saw with dismay that his communication with the right bank was compromised. Indeed, the French pressing on in superior numbers on the centre and left quickly left the issue of the battle little doubtful. A stream of fugitives was soon setting towards the bridges, and the Russian cavalry gallantly dashed forward to cover the retreat.

Meanwhile Senarmont's audacity grew greater with success. With a firm confidence in the invincibility of his splendid batteries he hurried them to the front once more, and again took them nearer still, so as to complete the ruin of the Russians, and assail their retreating columns in flank. With a true instinct he disregarded the artillery fire which was now poured upon him, and concentrated all the efforts of his guns towards consummating the ruin of the troops he saw before him trying to escape. The enemy's cavalry, noting his exposed position, swooped down upon his left flank.

In a moment he has swung his guns round to meet them; and two salvoes of grape are enough to shatter their effort, and the squadrons mown down by canister melt away. His terrible fire sweeps once more the road to Friedland, the Russian retreat becomes a total rout, and the fate of their army is sealed. The Russian loss has been variously estimated, as is usually the case where Napoleon's battles are concerned. Some French accounts say they lost as many as 80 guns, while, according to others, 17 only were captured. It is certain that the Russians fought with magnificent bravery, and that their resolution staved off what might have been a far more serious disaster. They left some 17,000 killed and wounded on the field, and 5000 prisoners fell into their enemy's hands, who on their part lost 8000 men and two eagles. [3]

But Friedland, whatever may have been the number of the trophies, was a most decisive victory as regards the consequences it entailed, and the combination against Napoleon was effectually for the time destroyed by it. Senarmont's brilliant action contributed in no small measure to the result of the day, and he received much credit for it. Never before had artillery played so independent a part, and it may be said that neither before nor since has the arm been handled with greater vigour and skill.

Whether in a modern battle calculated courage, such as has been described, could ever again hope to achieve so much seems impossible, but at least the promptitude with which an opportunity was seized and acted upon deserves our admiration and attention.

A quick eye and swift decision will never be at a discount, however, and even in the most scientifically conducted battle of our own day, it is possible that the surges of the fight may leave an opening in which an artillery general may again recognise his chance, and know how to turn it to account.

Senarmont's report gives his losses as follows:

Achievements of Field Artillery The Era of Napoleon: Part 1

Achievements of Field Artillery The Era of Napoleon: Part 2

1 officer and 10 gunners killed, 3 officers and 42 men wounded. The number of rounds fired was 2516, of which 368 were grape. 53 horses were killed.

Back to Age of Napoleon 29 Table of Contents

Back to Age of Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Partizan Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com