Finck's Advance to Maxen

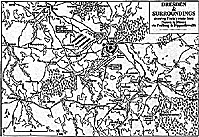

At this point, it would be helpful to refer to the map on page 41 and follow the advance of Finck's corps from its starting position at Nossen and on to Maxen via Freiberg and Dippoldiswalde. We begin on November 14th with Daun fal1ing back from Meissen and establishing a new position along the Plauensche-Grund, outside of Dresden. This defensive position extended southeast in the direction of Freiberg. Finck started his march from Nossen on this same date.

On November 16th, Finck arrived at Dippoldiswalde where he was now well in the rear of the Austrian lines and in a position to cut off one of the primary supply routes from Bohemia to Dresden. If the Austrians allowed Fmck to hold this position, then their only source of supply would be by river barge a1ong the Elbe.

On November 17th, Finck advances further behind Austrian lines

and occuppies the Maxen plateau. A look at the map indicates how

close Finck is to cutting off the Elbe supply route (from Maxen). This

would force the Austrians to abandon Dresden and conduct a difficult

and costly winter retreat.

On November 17th, Finck advances further behind Austrian lines

and occuppies the Maxen plateau. A look at the map indicates how

close Finck is to cutting off the Elbe supply route (from Maxen). This

would force the Austrians to abandon Dresden and conduct a difficult

and costly winter retreat.

Large Map (slow: 153K)

Jumbo Map (very slow: 330K)

On November 18th, Daun decides to attack Finck's exposed position at Maxen with a force of 23,000 Austrians, 9,000 Reichsarmee troops and some 2,000 Croats. Frederick was aware that the Austrian generals Sincere and Brentano were advancing towards Dippoldiswalde and closing in on Finck.

Frederick sent a message to Finck warning him of the potential danger, however, the king did not appear to take the threat very seriously nor did he order Finck to retreat. Frederick would wait an additional 36 bours before deciding to send Hulsen's relief force to open a line of retreat for Finck at Dippoldiswalde. Also on the 18th, Finck reported that he did not expect to engage the enemy there.

The Austrian Plan of Attack

The actual plan of attack was developed by Lt. General Lacy, who urged a reluctant Daun to take the nsk of attacking across broken, wooded terrain that seemed to provide a natura1 defensive position for Finck. Lacy was convinced that that the tactics successfully employed at Hochkirch the year before, i.e. converging columns of attack from all directions, would enable the Austrians to gain the Prussian positions before the latter could react. Lacy also argued that the very terrain that seemed to favor the Prussians could turn into an advantage for the Austrians, for they could approach Finck's Maxen position virtually undetected, thanks to the cover of the surrounding hills and forests.

Lacy's plan of attack consisted of the following elements:

-

[1] a blocking force of 9,000 Reichsarmee and Croat troops would

guard the crossing of the Muglitz River valley on the eastem side of

Finck's position;

[2] Brentano's corps of 6,000 troops would cover the western side of the Maxen position;

[3] the main strike force of 17,000 Austrians would advance towards Maxen from the south, via Hausdorf.

The Maxen Terrain

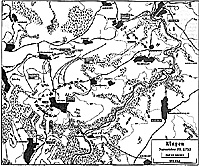

A brief description of the battleground is necessary before we

continue our story. Refer to the tactical map of the battlefield at right. [I would like to thank Paul Dangel for creating these maps specifically for this article.]

A brief description of the battleground is necessary before we

continue our story. Refer to the tactical map of the battlefield at right. [I would like to thank Paul Dangel for creating these maps specifically for this article.]

Large Map of Maxen (very slow download: 150K)

Jumbo Map of Maxen (Extremely slow download: 754K)

The principal terrain features are the Maxen plateau and the Muglitz River valley. The Maxen plateau dominates the center of the map and basically fol1ows the positioning of the Prussian troops, shown as black rectangles on the map, running from south of Maxen village and as far north as the village of Falkenhain (near the top of the map).

The Muglitz frames the eastern edge of the battlefield as well as a portion of the northern sector, with a steep and heavily wooded river valley. We can see that the Muglitz was 1ighty held by Reichsarmee Hoops (shown as shaded rectangles on the map) under the command of Stolberg and Kleefeld. The terrain is so rough that it hardly requires any troops to defend or block it.

The Maxen plateau rises fairly steeply from the Muglitz valley and is particularly steep to the south of the village, save for a narrow edge running from Hausdorf to Maxen. While on the Duffy tour, our party wallowed from the Heide Berg to Maxen and we were amazed that any troops were able to ascend the plateau through this incline, yet, as shown on the map, the righthand column of Austrian cavalry had to attack over this ground, and with considerable success.

Today, the main road from Hausdorf to Maxen fo1lows the edge line as it is the natural way to ascend the plateau. We followed the road in the footsteps of the righthand column of attacking Austrian infantry.

To the left of the main road, the ground undulates more gently, but it still remains a physical obstacle to attacking troops. The two lefthand columns of Austrian troops attacked over this ground.

The Duffy tour stopped stopped for a picnic lunch outside Maxen, at approximately the position occuppied by the Prussian fusilier regiment Grabow (IR47), shown south of Maxen village and to the left of the road from Hausdorf. To our right, as we faced Hausdorf, Duffy pointed out the likely position of the earthen artillery redoubt that is shown on the map.

South of us, it appeared that the only easy access to the Maxen plateau was via the roadway, for the rest of the ground in front of the Prussian line appeared too steep to attack, especially giving consideration to the fact that the ground was snowy, slushy and slippery. Indeed, Finck must have felt fairly confident in the strength of his position given the difficulty of the terrain.

Moving further south, the road begins to ascend towards Hausdorf, passing between two gentle hills, the Heide Berg and the Drei Berg. The Austrians placed their artillery (heavy 12 pound guns) on these hills and bombarded the Prussian position in front of Maxen village, apparently with good effect. The overshots actually sailed over the town and fell amidst the Prussian baggage train--our map indicates that this distance was over one mile! Our tour made a stop on the Drei Berg, approximately where the word Sincere appears on the map.

Here we looked back on tbe Prussian positions and almost to a man, our tour concluded that the distance from the Austrian batteries to the Prussian positions was too far away to be effective, but such was not the case. As wargamers, were are conditioned to think that long-range artillery fire is not effective.

North and west of Maxen the ground rises gently towards a hill called the Sand Berg, which was occupied by Brentano's Austrian corps of 6,000 men. Occational stands of trees dot the landscape today, and so there does not appear to be any signiflcant terrain obstacles in this sector of the battlefield.

Significant Numbers

Having seen the terrain, one can appreciate the fact that the Austrians did not have to deploy significant numbers of troops to hold and blockade the Muglitz valley. This task was assigned to Stolberg's Reichsarmee contingent consisting of 6 battalions of fusiliers and 5 squadrons of Austrian dragoons from the regiment Savoy (D9).

Stolberg covered a frontage of more than 3 miles. Kleefeld's Croats deployed around the wooded north end of the Maxen plateau to seal off this potential avenue of escape. Brentano's moderate force of 6,000 troops consisted of 6 Austrian musketeer battalions, some Croats, and 4 squadrons each of hussars and dragoons. They were supported by a considerable amount of artillery.

The main Austrian striking force made a covered approach towards Maxen via Hausdorf. This attack element of 17,000 troops was deployed into 2 columns of cavalry under the command of O'Donnell and 2 columns of infantry commanded by Sincere. Lacy assumed overall management of attack. The Austrians converged on Maxen from four sides during the night of November 19th.

Their troops were eager to attack, but the senior generals had some misgivings, and at Hausdorf, there was some sentiment to turn back. However, at the urging of Lacy and O'Donnell, the decision was made to launch the attack.

The 4 columns exited the valley leading to Hausdorf, a cloud of Croats followed by 2 continuous lines of grenadiers (5 battalions) were in the vanguard. The two cavalry columns deployed on each flank of the attack, forming into columns of squadrons. The 2 columns of infantry, 9 battalions in each, fonned in the center.

Again, we note that the Austrians were discarding the traditional linear formations of 18th Century warfare in favor of the more flexible converging columns of attack. This allowed them to employ their superior numbers to the best advantage and to favor speed of movement over firepower. It is also interesting to note the use of grenadier battalions as the spearhead of the attack.

The Prussian Forces at Maxen

Finck's 15,000 troops (11,000 infantry and 4,000 cavalry) consisted of 4 battalions of grenadiers, 13 battalions of musketeers/fusiliers of dubious quality, the freibattalion Salenmon; and the cavalry was comprised of 3 cuirassier regiments, 2 dragoon regiments, and the l0 squadron Gersdorf Hussar regiment (H7). Nearly half of these units had suffered heavy casualties at Kunersdorf, so their numbers were either depleted or made up with conscripts.

The musketeer regiment Rebentisch (IR11) was composed largely of Austrian and Russian prisoners who would have little incentive to do much fighting. Finck's command was augmented by 70 artillery pieces, include ing 43 fleld guns and 27 3-pound battalion guns. The reconstituted horse artillery battery, which had been captured at Kunersdorf, was included in the field artillery alotment (bad luck this lot!). So while this force looked imposing on paper, the truth of the matter is that it was very brittle.

Their generals were of better quality. Finck and his subordinate, von Wunsch, were well-regarded in the Prussian army, as were the principal cavalry commanders, von Bredow and von Platen. Finck, age 40, spent time in the Russian service before joining the Prussian army in 1743, where he commanded a grenadier battalion. He was a cousin of Frederick's confidant, General Winterfeldt, and rose rapidly in the Prussian service. Finck had commanded the diversionary force at Kunersdorf and is given credit for organizing the remnants of the Prussian army after that battle. As such, he was well-regarded by Frederick and deemed capable of independent command.

As stated ear1ier, Finck received a warning of the converging Austrian forces from Frededck on November 19th, but the king had not ordered a withdrawal nor did he indicate that the threat was serious. Likewise, Finck was unwilling to retreat on his own initiative and risk facing the wrath of the king, so he stayed put and awaited his fate.

Frederick must have finally realized the dire predicament that he had put Finck into, for he dispatched a relief force under Hulsen to open an escape route via Dippoldiswalde on November 20th, but this was to be too little, too late. Finck expected that he could hold his position until rescue by the king.

The Prussian Deployment

The Prussians occuppied the high ground overlooking the road from Hausdorf. Finck deployed a single battalion of the Willemy grenadiers (4/16) on his far left east of Maxen vi1lage. Closer to the main road, he deployed the Finck regiment (IR12), the Standing Grenadier Battalion No. 3 (Benckendorf) and the Zastrow (IR38) regiment - one battalion each, on the left hand side of the road facing Hausdorf. Continuing across the road, he deployed the Grabow (IR47) fusilier regiment, the Billerbeck grenadiers (13t26), and the Kliest grenadiers (37t40) - one battalion each. Two batteries totaling 11 field guns were deployed on this front.

On the far right of Finck's line, the 2 battalions of the Rebentisch (IR11) musketeer regiment were deployed perpendicular to Finck's front line and facing west. The infantry regiment Schenkendorf (IR9) was to their right. The rest of the ground between Maxen and Schnorsdorf was held by the Jung Platen (D11) dragoons and 3 regiments of cuirassiers: Vaso1d (C6), Horn (C7) and Bredow (C9), followed by 3 battalions of musketeers (IR29, IR21 and IR14) which extended the Prussian line to Schnorsdorf.

About a mile to the north of Maxen, Finck deployed von Wunsch with 2 battalions each of IR45 (Hesse Cassel) and IR36 (Alt-Munchow fusiliers), plus the freibattalion Salemnon (FB3) and elements of the Gersdorf Hussar regiment.

The battle map also places the rest of the Gersdorf Hussars (H7) and the Wurttemberg Dragoons (Dl2) in a fold of ground directly behind Finck's front line. These cavalry regiments would have been hidden from the Austrians' view, but unfortunately for Finck, they were in an excellent position to feel the effects of artillery overshots bouncing over the front line. This undoubtedly led to their poor performance during the battle.

Finck would have been better served by holding a strong position around Hausdorf, where he could have bottled up the Austrian advance up the valley. However, he did not have enough troops to cover all of the necessary ground, hence his reasoning of drawing the troops together around Maxen. During our tour, Duffy mentioned that 2 battalions of grenadiers and some hussars were initially deployed at Hausdorf, and these acted as a trip wire to warn Finck of the impending Austrian approach from this direction. These units then fell back to the main position at Maxen.

More Maxen

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. IX No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com