The Campaign of 1759

Christopher Duffy describes 1759 as "The Terrible Year" for Frederick the Great of Prussia, and for good reason. The campaign featured a string of severe defeats for the Prussians, starting with Kay (July 23, 1759), then Kunersdorf (August 12), Maxen (November 20) and Meissen (December 3). The total Prussian losses for the campaign of 1759 included 42,000 lost in battle and another 18,000 lost from disease and desertion, out of an army that numbered 130,000 at the beginning. Also included in these losses were many of the officer corps--losses that could not easily be made up.

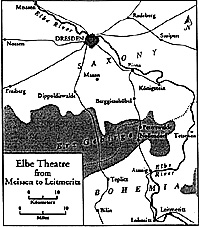

The first half of 1759 was characterized by a number of small raids on Austrian supply magazines in Saxony and Bohemia These were conducted quite effectively by Prince Henry's army. He struck into Bohemia in April, burning magazines, capturing 3,000 prisoners and destroying over 200 transport boats on the Elbe River.

Then in early May, Prince Henry turned west and attacked the Reichsarmee depots in Bamberg and Bayreuth. By June, Prince Henry was back in Saxony, encamped east of Dresden, near Bautzen, where he kept an eye on the activities of Austrian generals Haddik and Loudon who were operating in the Lausitz. These Austrian forces posed a potential tbreat to Berlin, hence the special attention received from the Prussians.

Prussian Defeats at Kay and Kunersdorf

Things started rather slowly on the eastern front, as the Russians did not depart from their bases in Poland until early June of 1759. General Saltikov's Russian force of 75,000 troops was watched by the Prussian general Dohna's covering force of 18,000. These were augmented with another 10,000 to 12,000 men under General Hulsen, giving the Prussians 26,000 to 30,000 troops facing the Russians.

Things started rather slowly on the eastern front, as the Russians did not depart from their bases in Poland until early June of 1759. General Saltikov's Russian force of 75,000 troops was watched by the Prussian general Dohna's covering force of 18,000. These were augmented with another 10,000 to 12,000 men under General Hulsen, giving the Prussians 26,000 to 30,000 troops facing the Russians.

Dohna's ill health and lack of enterprise led to his replacement by Lieutenant General Wedell, who hurled his small army against a strong Russian position at Kay on July 23rd. The Prussians lost 8,300 killed, wounded and prisoners in the battle of Kay and retired west of the Oder River. Saltikov now advanced his army towards Frankfurt-on-the-Oder.

Frederick was now forced to take matters into his own hands and go in person to stem the retreat posed by Saltikov's Russian army on his eastern border. First, he recalled Prince Henry's army from Saxony to keep a watch over Daun's Austrians operating in Silesia. Then, Frederick marched to the Oder River with a force of 21 battalions of infantry, 35 squadrons of cava1ry and over 70 heavy guns, to join the remnants of Wedell's army and finish off the Russians. (Frederick and Prince Henry actually switched armies to facilitate the quickest movement to the Oder).

Saltikov arrived in Frankfurt on July 30th and awaited the arrival of Loudon's corps of 18,000 Austrians. The combined force of over 90,000 men settled into a fortified camp at Kunersdorf, on the east bank of the Oder and waited for Frederick to attack. Frederick duly obliged the allies by launching his army of 50,000 men at the Kunersdorf position on August 12th.

The subsequent battle of Kundersdorf was an epic disaster for the

Prussians. After some initial success, the Prussians were thrown back

and eventually routed from the field. By the end of the day,

Frederick's army had disintegrated into a dazed clump of 3,000 to

4,000 men. Prussian losses were approximately 6,000 killed and

13,000 wounded and virtually all of the artillery (including the new

horse artillery battery) was abandoned or captured.

The subsequent battle of Kundersdorf was an epic disaster for the

Prussians. After some initial success, the Prussians were thrown back

and eventually routed from the field. By the end of the day,

Frederick's army had disintegrated into a dazed clump of 3,000 to

4,000 men. Prussian losses were approximately 6,000 killed and

13,000 wounded and virtually all of the artillery (including the new

horse artillery battery) was abandoned or captured.

The allies paid a high price for their victory, losing nearly 18,000 killed and wounded Their casualties, as much as any other factor, explains why Saltikov and Laudon did not follow up their victory with a vigorous pursuit of the Prussians.

By August 15th, Frederick managed to gather in 24,000 troops and this number would increase to 33,000 by month end The campaign now turned south towards Silesia, Lusatia and Saxony.

The Fall Campaign

Towards the middle of September, the military situation found Frederick and his army of 30,000 men covering Berlin from the south. The Russians and Austrians, with a combined force of 120,000, were extended across an 8-mile front between the Bober River and the upper Elbe River. This position cut Prince Henry's army of 38,000 men in Silesia off from the king's army. Daun's Austrians operated around Bautzen in the south, while Saltikov's Russians concentrated around Guben in the north.

It appeared that Daun and Saltikov were on the verge of joining forces to operate against Prince Henry in Silesia, but the latter pre-empted that possibility by moving his army west from Silesia and into Lusatia, astride the Austrian lines of supply. This move produced the desired effect as Daun abandoned his efforts to link up with the Russians, and instead, he followed Prince Henry's army into Lusatia.

By September 22nd, Daun (50,000) and Prince Henry (38,000) stood face to face at Gorlitz. As Daun prepared to attack, the Prussians quietly slipped out of their camp at night and marched west into Saxony. Prince Henry's army covered 50 miles in 56 hours, striking and capturing an Austrian detachment of 3,000 men at Hoyerswerda.

By September 22nd, Daun (50,000) and Prince Henry (38,000) stood face to face at Gorlitz. As Daun prepared to attack, the Prussians quietly slipped out of their camp at night and marched west into Saxony. Prince Henry's army covered 50 miles in 56 hours, striking and capturing an Austrian detachment of 3,000 men at Hoyerswerda.

Daun retreated to Bautzen to protect his supplies and he continued on into Dresden, guessing (correctly) that this city was Prince Henry's objective. Of course, Prince Henry's true goal was to lure Daun out of Silesia entirely and any other good fortune was simply incidental.

Daun joined the Reichsarmee at Dresden, then advanced up tbe Elbe, Pushing Finck's small force out of Meissen. Finck continued to fall back to a strong position at Torgau where he was joined by Prince Henry. On October 29th, Daun sent 16,000 troops under the command of Arenberg to turn Prince Hemy's right flank and push him out of Torgau. Instead, the Prussians pounced on this force at Pretsch in an action that lost the Austrians 4,000 men.

The Prince had planned to surround this detachment and destroy it completely, but the Austrians got word of the attack and retreated. Note how the Austrians held the initiative during the whole month of October, with twice as many troops as Prince Henry, and gained only a nominal amount of ground. Prince Henry, on the other hand, counterattacked and regained all of the lost ground in less than one week.

In a brief aside, the summer Kunersdorf campaign had denuded Saxony of all Prussian troops, save for a few garrisons in key cities. Foremost among these was Dresden, garrisoned by 3,700 men under the command of General von Schnettau.

On September 4th, after eight days of siege by a force of 30,000 Reichsarmee and 10,000 Austrian troops, von Schnettau was forced to surrender Dresden to the allies. He capitulated under favorable terms that allowed his men to march out of the city with all their weapons and a considerable quantity of supplies and money. The surrender was in compliance with an earlier set of orders from Frederick to surrender under the best possible terms and save the garrison from capture.

New Orders

Unbeknownst to von Schnettau, Frederick had sent new orders for the garrison to hold out until a relief force of Wunsch and Finck could arrive. The relief column arrived, sad to say, a day too late, as did the counter-manding orders from Frederick. Initiative was not the strong suit of the Prussian commanders under Frederick. Wunsch and Finck fell back to a strong position at Meissen then another one at Strehla, then finally at Torgau where they linked up with Prince Henry, as noted earlier.

Meanwhile, on the Oder River front, Frederick conducted a brilliant campaign of manouver that stymied Saltikov's attempts to capture either Glogau ar Breslau in Silesia. When Soltikov received the news that Daun was heading for Saxony rather than marching to the Oder, the Russian commander suspected bad faith on the part of Daun and so he retired his army to Poland for the winter, on October 24th. This left Frederick free to meddle in Prince Henry's successful campaign in Saxony; which brings us to the beginning of the Maxen episode.

November Campaign of 1759

At the beginning of November, Prince Henry held a strong position around Meissen with an army of 40,000 men. He was subsequently reinforced by a detachment of 13,000 men sent by Frederick, under the command of Hulsen. Daun, with approximately 60,000 Austrians and the 23,000 strong Reichsarmee, retreated from the Meissen posttion to Dresden on hearing of Hulsen's arrival.

On November 13th, Frederick joined Prince Henry's army and assumed command. He was impatient to drive Daun out of Dresden before the onset of Winter, and ignored the counsel of his brother to let well alone, for surely Daun would continue to retreat back into Bohemia if left to his own devices.

- "Henry never ceased to believe that he had had the situation

well in hand before Frederick arrived, and that he would soon

have won a brilliant success if the king had never come. In fact

Frederick accepted his plan of campaign, and the only

difference between his pursuance of it and Henry's was that he

was less methodical."

--Prince Henry of Prussia by Chester Easum page 118.

Henry had manouvered Daun out of successive positions in front of Torgau, Strehla and now Meissen, using the time-honored method of threatening Daun's flanks and supply lines. Henry's constant and methodical pressure had produced wondrous results so far, and if he had been allowed to continue at his own pace, he might well have driven Daun out of Saxony by the end of the year.

At this point, Frederick injected his royal personage into the fray by ordering Finck's corps of 15,000 men to make another flanking move around the Austrian left -- this time to Maxen, deep in the rear of the Austrian position where he could disrupt the movement of Austrian supplies from Bohemia to Dresden.

- "Frederick and Prince Henry quarreled bitterly when the

prince went in person to headquarters to protest against anyone's

being sent to Maren as things then stood The prince left the

king's quarters in a very angry mood, announcing to the world

his determination to quit the service at once. 'Since you are

absolutely determined on it, very well,' he was reported to have

said to his brother; 'but if trouble comes, as come it must, then

take upon yourself the responsibility for the disaster to the state.'

To his fellow officers, according to the same witness [de Catt] the prince said further: 'I spoke to him as a true patriot and a good brother, but he would not listen

to me. If the army were only placed a little more to the right,

nearer Dippoldiswalde, the danger would not be quite so great.'

-- Easum, pages 118-119

More Maxen

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. IX No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1997 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com