Contrary to the events in Cape Breton Island which eventually resulted in total victory for English arms, the war of posts that ebbed and flowed in the backwoods of Acadia and upper New England frequently culminated in bloody stalemate.

Contrary to the events in Cape Breton Island which eventually resulted in total victory for English arms, the war of posts that ebbed and flowed in the backwoods of Acadia and upper New England frequently culminated in bloody stalemate.

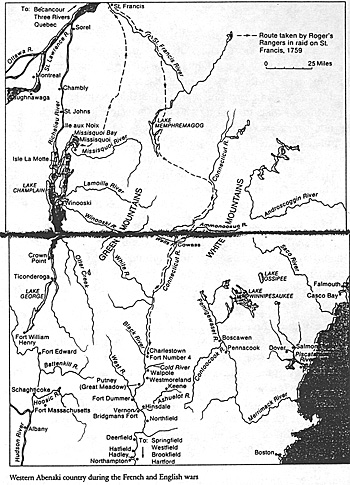

Western Abenaki country during the French and Indian Wars. Note that the French Fort Ste. Frederic occuppied the site shown as Crown Point on this map. Other points of interest include Fort Number 4, Fort Dummer, and Fort Massachusetts. The map comes from The Western Abenaki of Vermont, 1600 - 1800 ; by G. Calloway, Oklahoma, 1990.

The New Englanders, less familiar than the French and their Indian allies with the intricacies of forest warfare, were often put in a position where their superior numbers and better logistics meant little, as they were served up in penny packets to man isolated outposts or march forth in uncoordinated expeditions against their foes.

Jumbo Western Abenki Map (slow: 199K)

Skirmishes were constant along the sparsely settled frontier, but the numbers involved rarely exceeded a few score participants on a side. That these scattered battles occasioned no permanent gain for the victors, either territorial or political, and were, as often as not, negated by the outcomes of similar skirmishes elsewhere rendered them ultimately meaningless to anyone but the unfortunate participants themselves. The frontier boundaries remained unchanged; the French still ruled in Canada; the British remained masters of Acadia.

Attempts had been made by the English during the 1730's to foster friendly relationships with their Indian neighbors to the north who had traditionally allied themselves with the French. Hopes that these Indians would remain friendly or neutral in the event of war were soon dashed as many Abenakis and others cast their lots with the French. Governor George Clinton of New York estimated that the French had 600 warriors allied with them including 230 Caughnawagas, 90 St. Francis Abenakis, and 40 Missisquois. Within five years every English settler would be driven out of present-day Vermont.

Many of the French and Indian raids would emanate from the new French fort known as Fort St. Frederic at the southern end of Lake Champlain. Although the garrison of this fort in 1745 was small - one estimate shows 6 officers, 5 sergeants, and 88 enlisted men - it would be periodically augmented by additional raiding parties sent southward by the government in Quebec. With the declaration of war, these raids were not long in coming.

One of the first attacks took place on July 5, 1745, at Great Meadow at Putney, about 16 miles above Fort Dummer, where a settler, William Phipps, was seized as he hoed corn by two Indians who intended to take him prisoner. He killed one with a gun he had grabbed from one of them and wounded the other mortally with his hoe. As he was running on his way to freedom he was accosted by three others who promptly killed him for his efforts.

On October 11 or 12, 1745, a group of around 60 French and 12 Indians attacked the fort at Great Meadow again. They slaughtered the cattle and, after a fight of about an hour and a half, killed one Englishman and captured another, a 60-year old settler who died in captivity. Soldiers from Northfield and Fort Dummer pursued the French as far as Fort Number Four, where the raiding party split into two groups going in different directions.

On November 13, 1745, Sieur Marin, of whom we've heard earlier concerning his abortive relief expedition to Louisbourg, traveled to Fort St. Frederic with a view to offensive operations against upstate New York. He had with him a force of 280 French and 229 Indians accompanied by the Abbe Piquet. Hearing that Saratoga had a garrison of only 80 men, he attacked on the 28th. All buildings were destroyed, 12 English were killed and 109 taken prisoner. On the return to Fort St. Frederic, Fort Lydius was also put to the torch.

With the coming of the year 1746, the frequency of the raids increased. In the spring alone, French records indicate a total of thirty-five war parties were sent against the English frontier outposts. The English response to French and Indian aggression was feeble at best. Under orders from the government in England to maintain a defensive posture, all that could be managed was a raid or two against the French by some Mohawks under the sway of Colonel William Johnson, of whom more would be heard in the next war.

Attack at Number 4

After a series of skirmishes, the first of several major attacks against the Fort known as Number Four occurred on May 24, 1746. This fort, named after the settlement that it protected which was the fourth in a range of townships along the Connecticut River, was a square log stockade measuring 180 feet on a side and enclosing several houses. These houses were all arranged in a straight line and with their backs against one wall so that their roofs served as firing platforms. The logs of the stockade, instead of running vertically as in a typical frontier stockade, were squared off and lay horizontally, even having interlocking corners after the fashion of a log cabin. Flanking bastions were erected in all four corners of the fort.

On May 24 a French and Indian force of unknown size ambushed a troop of soldiers near the fort which was under the command of Captain Phineas Stevens. A relief column under Captain Stevens himself issued from the fort, and, after a brief fire fight, put the ambushers to flight. Five Indians and five English were killed and one Englishman was captured.

On the 19th of June Stevens and fifty men engaged another large war party in the woods at Number Four. As the Indians lay in ambush, Stevens detachment had issued from the fort, apparently on patrol. Many of the soldiers on the frontier had taken up the practice of using watch dogs to detect ambushes, and here it paid off, as the English advanced warily, heeding the actions of their nervous dogs. When one of the ambushers was detected and fired upon, all the others rose up and a battle ensued. After a hot fight, the attacking Indians, estimated to number 150, retreated into a nearby swamp. Indian casualties are unknown, since they dragged their fallen with them. The English suffered the loss of one man mortally wounded. On July 3, yet another Indian raid resulted in the death of an Englishman and the killing of cattle and several buildings torched.

In the early part of April, 1747, another party of some 60 French and Indians again attempted to besiege Number Four. The party, under command of Boucher de Niverville, ensign of colony troops, attempted to bluff the garrison of 30 men - still commanded by Captain Stevens - into believing that the attackers numbered 700 men! When verbal intimidation and fire arrows failed to convince the garrison of the strength of the attackers, two Indians came for ward to parlay with Stevens under a flag of truce. The supplies of the besiegers must have been far worse than those of the garrison because the Indians now offered to trade the English - their enemies - furs for corn. When the offer was turned down, the French and Indians shortly withdrew.

Attacks would continue at Fort Number Four for the remainder of the war, but none would seriously threaten it. In November, 1747, a war party would ambush and kill several men at the fort. As late as March, 1748, Indians on snowshoes would kill one man and capture another near the fort.

Fort Massachusetts

In August of 1746, M. Rigaud de Vaudreuil, the brother of the future governor of New France, resolved to attack Fort Massachusetts. Located on the Hoosac River, a tributary of the Hudson, Fort Massachusetts had been built in 1742 to defend the ever expanding frontier and was one of the last bastions of defense before Albany itself. The stockade was built in a fashion similar to that of Fort Number Four, with horizontal interlocking beams. The wooden wall rested upon a stone underpinning or foundation. There was a blockhouse on the northwest corner capped by a watch tower. The stockade enclosed a number of buildings including a large log building which overlooked the outer wall on the south side. It may have been loopholed for muskets. The complete garrison comprised fifty-one men commanded by Captain Ephraim Williams.

Williams was not present at the fort however. Earlier, a proposal had been made to invade Canada - called off by the reports of the approach of d'Anville's fleet. Williams and some of his men had departed to participate in this offensive and had not yet returned. Thus, the fort was left under command of Sergeant John Hawks with a diminished, dysentery-ridden garrison of 22 men, including himself and the chaplain, and minimal ammunition.

Vaudreuil arrived before the fort on August 29 with a very imposing force of 400 Canadians and 300 Indians. Vaudreuil had planned a general attack to commence under cover of night, however some of his troops got too enthusiastic and immediately began to bang away ineffectively with their muskets at too great a range from the fort to have any effect. With surprise lost, the French and Indians proceeded to invest the fort from the surrounding stumps and bushes. After a siege lasting 28 hours, the English finally surrendered. The French and Indian casualties had been one Indian killed and sixteen French and Indians wounded. The English had lost one killed and two wounded.

Vaudreuil next got word that a detachment of English was expected from the town of Deerfield to reinforce Fort Massachusetts. He sent a detachment of sixty Indians to wait in ambush. The English column, consisting of nineteen men, was cut to pieces, 15 of them being shot at close range and the remaining four taken prisoner. All prisoners from Fort Massachusetts were ultimately taken to Montreal from which those who survived would ultimately be repatriated. Fort Massachusetts would soon be rebuilt and would not surrender again during the war.

Contrary to the events in Cape Breton This old woodcut captures the sequence of horrors of a typical Indian raid: the sudden attack, the burning and the scalping, the procession of wailing prisoners.

Contrary to the events in Cape Breton This old woodcut captures the sequence of horrors of a typical Indian raid: the sudden attack, the burning and the scalping, the procession of wailing prisoners.

Various Other Raids

Such was the character of the border war that the clashes of arms are too numerous to describe in full detail here. Although some of the better known incidents have been described, the conflicts were practically continuous. In March, 1747, thirty French and Indians under Lieutenant Herbin attacked a party of 25 English en route to Albany near Fort Clinton, killing 6 and capturing 4. In late April of the same year some Mohawks and English attacked a group of 21 Frenchmen near Fort St. Frederic killing five of them. On June 30, 1747, the settlement of Saratoga, already burnt once in 1745 and subsequently rebuilt, was again attacked by M. de la Corne de St. Luc with 200 men. Forty Englishmen including their commander, Lt. Chews, were captured and many others drowned in the river trying to escape.

Debacle at Grand Pre

Before concluding this study, we now must turn our attention one more time to events in Acadia, or Nova Scotia. As mentioned earlier, one of the chief French goals in North America had been the recovery of Acadia. This had been one of the objectives of the two abortive naval expeditions of d'Anville and Jonquiere. With a view to cooperating with d'Anville's task force, M. de Ramesay had been sent to Acadia in 1746 with a large force of Canadians. When he heard of the disaster that had befallen the fleet, he withdrew from the environs of Annapolis Royal, which he had intended to besiege, and quartered himself at Chignecto. His force, augmented by Micmac, Malecite, and Penobscot Indians, was estimated at 1,600.

The English were alarmed by the presence of Ramesay's force at Chignecto and by the erection of a fort at Baye Verte on the neck of the Nova Scotia peninsula. When Ramesay moved to Minas to try to incite the inhabitants into taking up arms against the English, Governor Shirley decided that it would be necessary to dispatch troops to Acadia to counteract such influence.

Colonel Arthur Noble, with four hundred and seventy men from Massachusetts, was dispatched to Annapolis Royal, from which, with some soldiers from the garrison, they sailed for Minas. Meeting with contrary weather, The troops disembarked, on December 4th, 1746, at the foot of French Mountain on the southern shore of the Bay of Fundy and proceeded on foot toward their intended goal. After eight snowy days and nights, they reached the village of Grand Pre, the main settlement of the district of Minas, where they discovered no trace of Ramesay's force. On learning of the approach of Noble's troops, Ramesay had retreated to Chignecto. Accordingly, the English took possession of the settlement without firing a shot.

The village of Grand Pre consisted of a series of small wooden houses irregularly scattered for a distance of a mile and a half. The English, rendered suddenly smug by their good fortune proceeded to occupy about twenty-four of these houses with little concern of a counterattack. The framework for one or two blockhouses, five small cannon, and a supply of snowshoes had been left aboard the ships, and no one had the forethought to retrieve them.

In the meantime, Ramesay had not been inactive. Quickly he dispatched a message to La Corne, a Recollet missionary at Miramichi, asking him to join him with as many Indians as he could muster. He sent similar messages to other missionaries and priests in the area. Ramesay's plan was to surprise the English at Grand Pre with a night attack. Although Ramesay would not be able to command in person owing to some accident to one of his knees, he soon had assembled around him some of the best of the Canadian fighters to be found. Commanding in Ramesay's stead would be Coulon de Villiers, the future humbler of George Washington at Fort Necessity. He would have under him Beaujeau, of future Monongahela fame; the Chevalier de la Corne, Saint-Pierre, Lanaudiere, Saint-Ours, Desligneris, Courtemanche, Repentigny, Boishebert, Gaspe, Colombiere, Marin, and Lusignan.

On the 23rd of January, 1747, Coulon's party departed for Grand Pre. Marching on snowshoes with sledges, they marched to Cobequid where they met Girard, the priest there. He informed them that the English at Grand Pre numbered between four hundred and fifty to five hundred. Undaunted, the French pressed on. Coulon eventually had Beaujeu divide the command into ten parties which were to be used to make simultaneous attacks against ten houses occupied by the English. On the 10th of February, they approached some houses that were located very near their destination. The houses were occupied by Acadians friendly to the French cause who immediately informed them which houses were occupied and by whom at Grand Pre.

Coulon, armed with this vital knowledge, detailed each of his ten squads to attack ten key houses known to harbor one or more important officers. Coulon himself, accompanied by Beaujeu and between fifty and seventy-five men, would attack a stone house near the middle of the village where the main guard was posted. The second party commanded by La Corne and consisting of forty men would attack a neighboring house occupied by Noble and several other officers. The remaining squads of twenty-five to twenty-eight men would attack other houses believed important to occupy. Beaujeu estimated the total French force as consisting of around three hundred men, whereas the English estimated the French at five or six hundred. The English force was over five hundred.

Under the cover of night and snowstorm the ten groups descended on their intended targets. The main group immediately lost its way in the snow and darkness and missed the stone house they had intended to assault, attacking instead a small wooden one nearby. It was too late to change the plan, and the French boldly rushed forward shooting down the bewildered guard before he had a chance to fire his weapon. Bursting through the doorway, the French had the house secured within minutes with the loss of two wounded including Coulon himself. Of the garrison of twenty-four, twenty-one English were soon dead and the other three were prisoners.

La Corne's party met with similar success against the house of Noble, killing the latter along with several other officers. Coulon's party, now commanded by Beaujeu, proceeded to go to the assistance of the other parties which were meeting with mixed success. Although the parties of Colombiere and Boishebert had each captured a house, that of Marin, consisting of twenty-five Indians, had been repulsed from its objective.

With the arrival of daylight, Beaujeu sent Marin to look for La Corne, who was now in command in lieu of Coulon. It had come to pass that those English who had not been killed or captured had taken refuge in the stone house in the middle of the village. Here La Corne was blockading them and attempting to force them to surrender. Beaujeu and his party joined La Corne immediately. A brief siege commenced with neither side doing much harm to the other until the English foolishly sallied forth to try and take the house occupied by La Come. Lacking snow shoes, they soon all foundered in the snow where they became sitting ducks to the French attackers. At length, on the following day, realizing the hopeless of their situation, Goldthwait, the new English commander, proposed terms of capitulation.

According to the agreement, the English were allowed to march with full honors of war back to Annapolis. The estimates of casualties vary. The English claimed that seventy English were killed and sixty captured. They claimed that the French suffered four officers and forty men killed and as many injured. The French claimed that the English suffered one hundred and thirty killed, fifteen wounded and fifty captured while French losses were seven killed and fifteen wounded. Of the eleven houses attacked, ten were taken.

In spite of their stellar victory, the French did not remain long at Grand Pre. Because of a lack of food they removed to the town of Beaubassin. The English resolve to hold Acadia remained unshaken in the face of disaster. In April a body of Massachusetts men sent by Governor Shirley reoccupied Grand Pre. All the French efforts at securing Acadia had been for naught.

King George's War 1744-1748

- Declaration of War

The Siege of Louisbourg

The Capitulation of Louisbourg

Plans for Further Conquests

The Border Wars

The Peace of Aix-La-Chapelle

Conclusions and Critique

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VII No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related publications are available at http://www.magweb.com