(Otherwise Known as The War of Austrian Succession in North America)

(Otherwise Known as The War of Austrian Succession in North America)

This article is a brief survey of the events of the War of the Austrian Succession in North America. Because most of the source materials consulted emphasize operations in Nova Scotia and Louisbourg, by necessity so does this article. This focus is justified in part by the fact that most "conventional" military operations took place in those locales. Nevertheless the many skirmishes between the French and their Indian allies against the New Englanders, notably in upper New York and present day Vermont, Maine, and New Hampshire, should not be underestimated. I have tried to include some of the more significant of the latter in this article.

The reader should be made aware that during this period of time, the French and the British were making use of two different calendars. France had adopted the modern, Gregorian calendar the dates of which were 11 days later than the English Julian calendar. Thus an English date of May 5th, old style, would be May 16th, new style. In all cases, I have used the new style dates unless otherwise noted.

Declaration of War

Upon the death of the Holy Roman Emperor and Austrian Archduke Charles VI in late October, 1740, a succession crisis ensued which was eventually to engulf England and France once again in military conflict. This conflict was to be fought in the backwoods of America as well as upon the fields of Europe.

England, already at war with Spain (the War of Jenkin 's Ear) over the question of trading rights since October, 1739, found herself at odds with France over the choice of a new successor to the throne of the Holy Roman Empire. Although many of the great powers of Europe, including Great Britain, France, Prussia, Russia, and the Netherlands, were signatories to the "Pragmatic Sanction" recognizing Maria Theresa as Empress of Austria and Queen of Hungary and her husband, Francis Stephen of Tuscany, as Holy Roman Emperor, a coalition was soon forged between Bavaria, France, Spain, Prussia, and Saxony against Austria, Hungary, Bohemia, Sardinia, and England.

Although backing rival claimants to the Imperial throne, the two nations of France and England had avoided formal conflict and were legally at peace during the Battle of Dettingen in 1743. However on March 15, 1744, France declared war on England. "King George's' War" had begun.

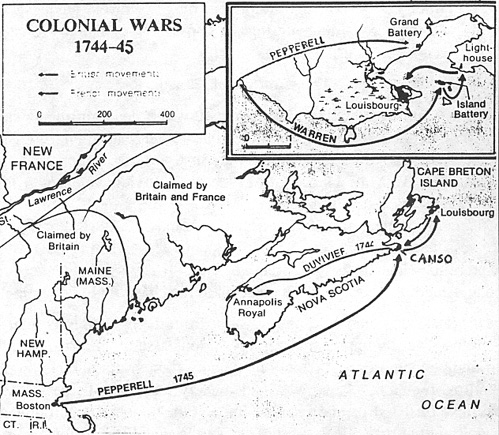

Map depicting the theater of operations for King George's War with emphasis on the Louisburg expedition and operations in Acadie (Nova Scotia). The map is supplied by the author from The Colonial Wars, by A.R. Carter, Chicago, 1992.

France and England had not been at war since the Treaty of Utrecht, in 1713, had put an end to the War of the Spanish Succession. France had emerged from this war victorious nearly everywhere except in North America where she had been forced to cede Acadia, Newfoundland, and Hudson's Bay to England. In the Spring of 1744 the French in North America found themselves at a vast numerical disadvantage in comparison to the British colonies along the Atlantic. It has been estimated that there were no more than 90,000 French in the New World compared to a British population of one million.

In spite of these daunting odds, the French pursued an aggressive military course with a view to regaining many of those areas lost to the British by the Treaty of Utrecht, especially Acadia. The French minister of the navy, Jean Frederic Phelypeaux, Comte de Maurepas, sent blank commissions, or letters of marque, to the military governor, Jean-Baptiste Louis le Prevost Duquesnel, along with numerous notes urging the conversion of fishing vessels to the occupation of privateering.

The Capture of Canso

The French in Canada received news of the declaration of war between France and England somewhat earlier than their English counterparts in New England, and they lost no time in preparing an offensive. By May 14 Captain Francois Duvivier was sent from Louisbourg by the military governor with a force of 351 men (22 officers, 80 French and 37 Swiss soldiers, and 212-218 sailors) and 17 vessels (two privateers, 1 supply sloop, & 14 fishing boats) to capture the English fishing village of Canso (also spelled Canceau) on an island of the same name adjacent to the coast of Nova Scotia.

This post, separated by a narrow strait from the Nova Scotia mainland, was wholly unprepared for any serious assault. Garrisoned by around one hundred and twenty men under Captain Patrick Heron of Phillips' regiment, Canso was inadequately fortified. These fortifications consisted primarily of a timber blockhouse in such abject condition that the officers of the garrison frequently paid for repairs out of their own pockets.

Taken completely by surprise, the garrison surrendered on that same day, May 24, after a brief bombardment by the privateers. Total English losses were I killed and 3 or 4 injured, all in an-armed sloop under command of Lieutenant George Ryall. This sloop also surrendered to the French after a brief fight. The French victors felt that they lacked sufficient strength to occupy the place, so, after carting away all the booty and prisoners that they could carry, they burned the settlement. The loot and prisoners were carried to Louisbourg from whence the prisoners were eventually to be repatriated back to Boston in return for French prisoners held by the British.

The Attack on Annapolis Royal

With the arrival of summer there was a palpable shift in the course of the war. More and more privateers were being commissioned out of New England to counter the French maritime threat. An escalating number of French fishing ships were being captured ever closer to Louisbourg. This did not help to augment an already badly depleted food supply there.

In spite of these vicissitudes, the French continued with an aggressive strategy, planning an attack on Annapolis Royal, the capital of Nova Scotia, formerly known as Port Royal. Annapolis Royal was not in much better shape to sustain an attack than the fort at Canso had been. Its fort was built of sandy earth which did not stand up well to the elements. It had been temporarily repaired with timber, but permanent repairs had not yet been effected. The garrison consisted of five companies, each of 31 men, all under the command of Major Paul Mascarene, the son of a Huguenot refugee. The fort was large enough that an adequate garrison would have required 500 men.

On the 12th of July a French besieging force of around 300 Micmac and Malecite Indians and a handful of French, including a missionary to the Micmacs named Jean-Louis Le Loutre, opened an attack on Annapolis Royal. Little was accomplished that day except for the killing of two British soldiers who had ventured out of the fort against orders. A few buildings were set on fire, but the attackers were quickly driven away by artillery and musket fire. They retreated to a hill about a mile from the fort to await promised reinforcements which never came.

Instead, four days later, two English vessels, the Prince of Orange and a transport vessel, sailed into the harbor bringing a reinforcement of 70 men to the besieged garrison. This reinforcement was followed shortly thereafter by an additional 40. Both reinforcements, however, had been sent without arms, and the fort did not have sufficient supplies on hand to provide them with weapons.

Le Loutre and his Micmac allies had apparently been expecting French naval assistance because, when the British boats carrying the additional troops first appeared before the besieged port, the French and Indians rushed to the shore to greet the troops. Then, quickly realizing their mistake, they retreated back into the woods. This addition to Mascarene's force was sufficient to demoralize the Micmac besiegers and cause them to retreat to the Acadian settlement of Minas.

It is not known for certain who originated The failure of the first attempt against Annapolis Royal may have contributed to the Acadian neutrality which generally prevailed throughout the war. As a result of the Treaty of Utrecht, the Acadians had been declared subjects of the King of England and had sworn an oath not to take up arms against him. They had also been promised by their British conquerors that they would not be required to fight against their French kinsmen in the event of war. Thus the neutral Acadians" frequently found themselves in the awkward position of trying to maintain a delicate balance of allegiances between the French troops who constantly demanded assistance of them and the British who regarded any hostile Acadian action as a treasonable one.

It is not known for certain who originated The failure of the first attempt against Annapolis Royal may have contributed to the Acadian neutrality which generally prevailed throughout the war. As a result of the Treaty of Utrecht, the Acadians had been declared subjects of the King of England and had sworn an oath not to take up arms against him. They had also been promised by their British conquerors that they would not be required to fight against their French kinsmen in the event of war. Thus the neutral Acadians" frequently found themselves in the awkward position of trying to maintain a delicate balance of allegiances between the French troops who constantly demanded assistance of them and the British who regarded any hostile Acadian action as a treasonable one.

Toward the end of July, 1744, plans were again set in motion for an attempt on the Nova Scotian capital. This plan depended on two contingents, one on land and one at sea. A force of regular troops from Isle Royale was to land at the Chignecto Isthmus and advance on Annapolis Royal, where they were to rendezvous with several hundred Micmac allies. As they marched they were to recruit as many Acadian volunteers as possible. In the meantime, two French vessels, the Caribou (52 guns) and the Ardent (64 guns) were to arrive off the coast of Annapolis. They were to carry supplies and additional troops and, after putting them ashore, would then impose a blockade of the port thus preventing a relief force from lifting the siege.

This expedition was under the command of Duvivier, the victor at Canso. His subordinate commanders were Louis Du Pont Duchambon de Vergor, enseigne en pied, Michel Rousseau, enseigne en second, and Gobet (or de Caubet), enseigne en second. With five vessels under his command including his own schooner Succes, Duvivier, his junior officers, nine cadets, one sergeant and 19 soldiers set off on July 29.

Sailing against strong headwinds, Duvivier made landfall at Port Toulouse only on August 2. Here he made arrangements for the Micmac support that was deemed necessary to any serious effort against the British in Nova Scotia. It is likely that the Abbe Pierre Maillard, who was a missionary to the Micmacs of Isle Royale, joined the expedition here.

The expedition departed from Port Toulouse on August 3, again in the face of contrary headwinds. On August 6, they sailed into Port La Joye at Isle Saint-Jean. Here the Succes was turned over to the command of Louis du Pont Duchambon, the commandant of Isle Saint-Jean and acting governor of Isle Royale (Cape Breton Island), who shortly sailed to Louisbourg.

Duvivier's force was augmented by additional troops on Isle SaintJean so that he now commanded five officers, 11 cadets, one sergeant and 37 soldiers. On August 7, this small force sailed once again and landed at Baie Verte on August 8. Making their way overland, they reached the Acadian community of Beaubassin five days later. Here Duvivier spent several days vainly exhorting the inhabitants to join his expedition. The French officials must have realized that the chance of Acadian military support was minimal since only two hundred and fifty muskets had been sent to arm them. Only a very few recruits were found who were willing to bear arms against the English at Annapolis Royal. Duvivier met with similar disappointment several days later at Minas, although, on August 27, he received a reinforcement of 70 Malecite warriors who were swiftly armed with muskets, powder, and shot.

As a result of various meager reinforcements, the "army" that appeared before the walls of Annapolis Royal on September 8 barely numbered 280 men. This was clearly not enough to force the submission of the fort whose walls had been strengthened and whose garrison now consisted of some 250 soldiers. Everything now hinged on the arrival of the warships Ardent and Caribou. What Duvivier did not know was that there had been a change of plans; the promised naval support would never arrive.

Although the Caribou had been in port at Louisbourg at the time of Duvivier's departure, the Ardent had not yet arrived, but was expected soon. In fact, the Ardent did not make landfall at Louisbourg until August 16 and was in need of serious repairs, most notably to a broken bowsprit. As a result, it would not be ready to sail for Nova Scotia until September 5th or 6th at the earliest. A junior officer of the garrison, de Renon, was sent to inform Duvivier of this delay but had not yet found him by the end of August. Ultimately, in the face of increasingly successful privateering expeditions by New England ships and the presence of British warships ever closer to the capital, Duquesnel reversed his decision to send the Caribou and Ardent to Annapolis Royal, retaining them to counter the British naval threat to the French colony. De Renon had already departed to tell Duvivier of the anticipated arrival of these two ships before Annapolis Royal by September 8 and was not aware of this change of plans. De Renon reached Duvivier on September 5 with his now obsolete news, and plans were made for the capture of the British fort based upon the anticipated naval support.

To intimidate Mascarene and his garrison, Duvivier marched his force before the fort with colors flying and established an encampment about a mile away. He also attempted to deceive the defenders as to the size of his force by arranging his march columns with the outer ranks complete but the centers devoid of soldiers so that it appeared that he had twice as many troops as he actually possessed. Apparently the ruse worked since Mascarene believed that there were "Six or Seven hundred men" facing him.

Starting on the evening of September 9 Duvivier launched the first of what were to become a series of nocturnal harassing attacks. Knowing that he lacked sufficient numbers to take the post by storm, he hoped to draw a maximum psychological advantage from these attacks while continuing to conceal from the defenders the paucity of his force. He further dispatched a note via his brother, Ensign Joseph Du Pont Duvivier, to Mascarene on the 15th of September in which he indicated the imminent arrival of three French warships (a seventy-gun, a sixty-gun, and a forty-gun) as well as 250 more regulars with cannon and mortars.

This psychological warfare apparently had some effect. Most of Mascarene's officers were in favor of negotiating an honorable surrender to the besieging troops. However Mascarene demurred. In response to the timidity of his officers, he embarked upon a pretense of preliminary negotiations with no real intention of surrendering his post. Upon determining the true morale of his troops, who were more dismayed by the prospect of their officers treating with the enemy than by their besieged predicament, Mascarene convinced his officers to break off negotiations and continue fighting.

On September 23 Duvivier resumed his harassment attacks earlier employed, although now with very little consequence. The garrison of the fort had come to realize the ineffectiveness of such tactics and now regarded them with contempt.

On September 26 two ships sailed into the harbor bearing British reinforcements in the form of " ... 53 Amerindians and rangers under Captain John Gorham from Boston." Then, on October 2, Captain Michel de Gannes de Falaise arrived from Louisbourg to inform Duvivier that the expected ships would not be arriving and that a continuation of the siege was pointless. On October 3 the siege was lifted and the French retreated. Annapolis Royal was secure once more.

King George's War 1744-1748

- Declaration of War

The Siege of Louisbourg

The Capitulation of Louisbourg

Plans for Further Conquests

The Border Wars

The Peace of Aix-La-Chapelle

Conclusions and Critique

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VII No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related publications are available at http://www.magweb.com