It is not known for certain who originated the idea for the siege and capture of Louisbourg. One frequently mentioned candidate is Lieutenant John Bradstreet. He was among those soldiers captured by the French at Canso and transported to Louisbourg. He'd had the opportunity to observe the less than ideal conditions that obtained there and had implored Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts that an invasion be launched. William Vaughan, a fish and timber merchant from the Maine coast, had also urged the governor to attack the place with militia. Governor Shirley was quickly convinced of the soundness of the idea and preparations were made to seize this important fortress.

It is not known for certain who originated the idea for the siege and capture of Louisbourg. One frequently mentioned candidate is Lieutenant John Bradstreet. He was among those soldiers captured by the French at Canso and transported to Louisbourg. He'd had the opportunity to observe the less than ideal conditions that obtained there and had implored Governor William Shirley of Massachusetts that an invasion be launched. William Vaughan, a fish and timber merchant from the Maine coast, had also urged the governor to attack the place with militia. Governor Shirley was quickly convinced of the soundness of the idea and preparations were made to seize this important fortress.

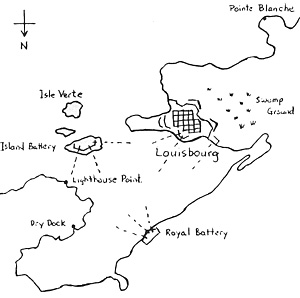

The harbor defenses of Louisbourg in 1745. Note the fields of fire from the shore batteries as indicated by the dotted lines.

The very existence of Louisbourg had been made necessary by the Peace of Utrecht. With the British territorial acquisitions of Newfoundland and Acadia (present day Nova Scotia), the French control of the mouth of the St. Lawrence river had been seriously undermined. A successful British blockade of the river would sever the supply line of most of New France, jeopardizing Quebec, Montreal, and the other riverine outposts necessary to French control of Canada. Thus, Isle Royal (or Cape Breton Island) and Isle St. Jean (Prince Edward Island), long claimed but heretofore unoccupied by France, were now considered vital to the survival of French interests in North America.

The colony of Isle Royal was founded in September, 1713, with the landing at Louisbourg of a detachment of Les Compagnies Franches de la Marine. From 1720 until the eve of the siege itself a series of stone fortifications were constructed to protect the settlement from attack. These works were constructed along guidelines that had been established in Europe by the famous French engineer Sebastien Le Prestre de Vauban in the previous century.

Known as the "Dunkirk of America" or the "Gibralter of the New World," Louisbourg was an imposing fortress, but with many weakhesses. The city was protected on the landward side by two bastions and two demibastions connected by walls. One end was anchored on the rocky shore of the ocean and the other, on the inside of the port past the Dauphin Demibastion. These works were intended to protect the city from landward assault. The main concentration of artillery could be found on the port side. The Piece de la Grave had embrasures for 27 of the heaviest cannon as did the Dauphin Demibastion. The entrance to the port was protected by an island with a battery mounting 36 guns. It was protected by a separate battery across the harbor and about one nautical mile north-east of the Dauphin Demibastion.

It is not known for certain who originated This battery was named the Royal Battery and contained 30 guns. The French defenders felt that an assault on the fort from the landward side was virtually out of the question owing to the presence of numerous marshes and bogs in that quarter.

It is not known for certain who originated This battery was named the Royal Battery and contained 30 guns. The French defenders felt that an assault on the fort from the landward side was virtually out of the question owing to the presence of numerous marshes and bogs in that quarter.

Despite their formidable appearance, the defenses of Louisbourg contained many serious defects. Neighboring hills overlooked a portion of the walls enabling properly emplaced guns to fire over the. glacis and into the interior of the town. Also the climate of Isl,C Royal was not conducive to the preservation of masonry. With short, wet summers and long, cold winters, the mortar that held the stone walls together never properly hardened. Because of the continuing cycle of freezing and thawing, the walls were constantly being undermined and in danger of collapse. Much of the stonework had to be covered by boards to shore it up. Finally, there was a serious shortage of cannon. Although Louisbourg was designed to mount 250 guns, Bradstreet reported that in fact there were only 100 present on the walls.

Louisbourg had a permanent garrison of eight compagnies of navy troops (les Compagnies Franches de la Marine) totaling 560 men supported by 150 Swiss soldiers of the Karrer regiment and 25 cannoniers. Bradstreet estimated that there might be a further 1,800 militia. Under normal circumstances, this garrison should have been sufficient to enable Louisbourg to withstand a prolonged siege, however for a variety of reasons, the morale of the troops was at an alltime low.

As a result of a poor harvest the previous year and because of the British blockade, there was a shortage of food which had necessitated rationing. Also, on December 27th, 1744, the garrison had briefly mutinied. The incident which had initiated the mutiny was the issuing of rotten vegetables to the troops at a time when fresh vegetables were being sold to the citizens of the town.

The garrison had a number of additional grievances. A share of the booty taken at Canso had been promised, but never delivered, to the soldiers. They demanded an increase in their allotment of firewood, full uniforms for the 1741 recruits, extra pay for work done repairing the fortifications, and reimbursement of their pay which was six months in arrears. All the soldiers joined in the mutiny except for the sergeants of the free companies and the artillerists. Although the mutineers eventually dispersed, after the authorities had acceded to their demands, a feeling of tension continued to pervade the outpost.

Reports of these weaknesses were communicated to Shirley in exacting detail by the repatriated Canso prisoners who had been given great latitude to wander the ramparts by their erstwhile captors. Once Shirley was convinced of the desirability of an attempt on Louisbourg, he convened the General Court of Massachusetts to gain approval of the scheme. Although initially rejected by the court, the issue was reconsidered several days later, passing eventually by the narrow margin of one vote, one member having providentially fallen and broken his leg while rushing to the House to cast a "no" vote.

Shirley's plan of attack envisioned a descent upon Louisbourg by a force of some two thousand New Englanders supported by ships from New England and by a squadron of British ships then stationed in the Leeward Islands in the West Indies and commanded by Commodore Peter Warren. He wrote to the commodore requesting assistance. Although Warren initially ruefully declined Shirley's request for support, stating that he lacked orders from the Admiralty, these orders approving Shirley's plans soon came. Warren lost no time in departing from Antigua with his flagship, Superbe (60 guns), Mermaid (40), Launceston (40), and a transport on March 24.

Shirley's proposal for an attack on Louisbourg met with a mixed reception from the other colonies. New York, still engaged in active, although clandestine, trade with both Montreal and the French West Indies was reluctant to take an active part in the war. Likewise Pennsylvania, ruled by pacifistic Quakers and more interested in commerce than bloodshed, chose not to participate. Rhode Island, still chafing over the way its founder, Roger Williams, had been mistreated by Massachusetts years before and embroiled in a border dispute with Massachusetts, was inclined to provide only token assistance. Only the New England states were motivated to seize Louisbourg and put an end once and for all to this haven of privateering.

Presently, Shirley and the other governors of New England cobbled together an army of inexperienced, but nevertheless enthusiastic, soldiers for this ambitious operation. Massachusetts, which at that time included all of modern-day Maine, contributed 3,300 men - by far the largest single contingent. Connecticut provided 516 soldiers and New Hampshire, 454. These troops were under the command of a merchant from Kittery, Maine, by the name of William Pepperell. Pepperell, promoted to the rank of lieutenant-general for the expedition, had virtually no previous military experience but was a close ally of Shirley, having lobbied on his behalf during the debates over the practicability of Shirley's plans, and was a popular leader with a reputation for sound judgment.

The army of 4,270 men was divided into nine regiments with the following commanders:

- First Massachusetts Regiment - Col. William Pepperell

Second Massachusetts Regiment - Col. Samuel Waldo

Third Massachusetts Regiment - Col. Jeremiah Moulton

Fourth Massachusetts Regiment - Col. Samuel Willard

Fifth Massachusetts Regiment - Col. Robert Hale

Sixth Massachusetts Regiment - Col. Sylvester Richmond

Seventh Massachusetts Regiment - Col. Shubael Gorham

Connecticut Regiment - Col. Andrew Burr

New Hampshire Regiment - Col. Samuel Moore

Shirley had also managed to assemble a small fleet of ninety transports and the following warships. all from New England and under the command of Captain Edward Tyng:

- The Frigate Massachusetts (24 guns) - Tyng's flagship

The Caesar (20)

The Shirley (20)

A type of vessel known as a snow (16)

A 12-gun sloop and two of 8 guns

The Boston Packet (16)

Two Connecticut sloops (16)

The Rhode Island sloop Tartar (14 carriage guns, 12 swivels)

A Rhode Island privateer (20)

A New Hampshire sloop (14)

In one vital area the New Englanders had a serious deficiency. This was the artillery. For battering the massive stone walls of the largest fort in North America, they could only count a mere 34 pieces: 8 @ 22-pounders, 10 @ 18's (New York's sole contribution to the effort), 12@ 9's, and 4 mortars ranging in size from 9" to 12". They hoped to make up the difference with naval guns from the fleet and by capturing French ordnance from the outworks of Louisbourg itself. With this latter goal in mind they brought along a large supply of 42-pound balls to be used in these captured guns. Incredibly, this optimistic preparation was eventually to bear significant fruit.

Pepperell's small flotilla set sail from Boston on the 4th of April. Its immediate destination was Canso where the ruined settlement was to be reconstructed and garrisoned as a point d'appui for further operations. The fleet reassembled at Canso by the middle of April, and, on May 4th, Commodore Warren arrived. He had with him 4 ships; the Superbe (60), the Mermaid (40), the Launceston (40), and the Eltham (40).

At Canso a pre-framed blockhouse was erected. Armed with 8pounders, it was named "Cumberland" in honor of the Royal Duke. Upon hearing that Louisbourg was yet ice-bound, the fleet waited at Canso for four weeks. Two companies of 40 men each were detailed to remain at Canso as a permanent guard, and Jeremiah Moulton's regiment was sent overland to attack and burn the French settlement at St. Peter's. This latter force soon returned without having attained its objective, the men having been intimidated by the presence of several French vessels and some Indians. The indiscipline of the New Englanders was showing. When word finally arrived that Louisbourg was free of ice, the rest of the army and fleet departed for their intended destination on May 9th.

From the viewpoint of the New Englanders, the day of the landing on Isle Royal could have only been regarded as one of either divine approbation or purest serendipity. On the morning of May 11th, residents of Louisbourg awoke to see a vast flotilla of ships round the cape and sail towards Flat Point in Gabarus Bay. Amid the tumult of bells ringing and warning guns firing, hasty measures were taken to prepare for battle. The wall of the southeast part of the fortress was shored up with a platform of planks upon which two 24-pounder cannon were quickly mounted. After some untimely vacillation, Duchambon finally sent off a small force of 50 civilians under command of Port Captain M. Morpain and 30 soldiers under Duchambon's son, Mesillac Duchambon, to oppose the landing of the New England troops, who, by 9 or 10 o'clock, were already at anchor in Gabarus Bay. Morpain's detachment was to be joined by 40 more soldiers who were already on watch near the place where it was assumed the New Englanders would land.

The New Englanders had decided to make their landing between Flat Point and Freshwater Cove, or Anse de la Cormorandiere, on an area of land about three miles from town and four miles from the Royal Battery. Observing the 80-man force sent to oppose the landing, Pepperell at once sent several boatloads of men toward Flat Point as a diversion while the main body, lead by Col. John Gorham and his company of Indian Rangers, pulled toward Freshwater Cove. Pepperell's ploy worked, keeping Morpain and Duchambon sufficiently preoccupied with Flat Point as to allow for the debarkation of the first 100 men of the New England force to be made entirely unopposed.

When the French discovered Pepperell's deception, they raced toward Freshwater Cove only to be met by the broadsides of three ships under command of Captains Fletcher, Busch, and Saunders as well as Provincial musket fire. After a brief skirmish, the French retired with a loss of 6 killed, 5 wounded and one civilian captured. The New Englanders suffered 2 or 3 slightly wounded. By nightfall, fully two thousand men had landed. The remainder made it ashore the next day. The New Englanders quickly established their first camp on the Island of Cape Breton probably on the banks of a small stream, now known as Freshwater Brook, running into Gabarus bay about I mile south-west of Louisbourg, thus assuring themselves of a convenient source of potable water as well as easy communications with the fleet.

The swift, effortless descent of the New Englanders upon French soil caused such anxiety and consternation among the citizens of Cape Breton that the inhabitants burned the houses and outbuildings outside the West Gate of Louisbourg and retired in haste inside the walls of the fortress. The elated New Englanders, undisciplined and not having as yet received any orders, began to range throughout the woods and hillocks of the area in large numbers, more as if this were an outing in the country than a military action. Some of these groups of men, wandering in the proximity of the King's and Dauphin's bastions, provoked the defenders into firing several ineffective rounds of artillery at them.

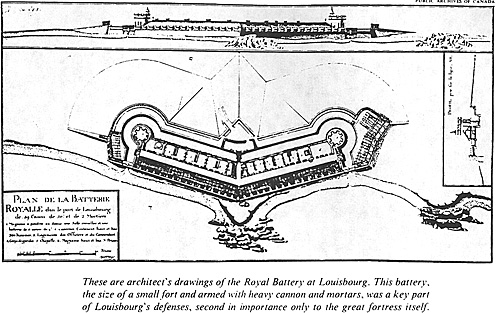

In the meantime, Duchambon was once again showing that, as a commander of the most formidable post in French North America, he was out of his depth. Failing to assemble a force that could have assaulted the confused and disorganized mob assembling itself outside the fortress walls, he wasted precious time calling for a council of war. At issue was the apparent vulnerability of the Royal Battery to assault from the landward side. Mounting 28 42-pounder guns and 2 18's, and commanded by Captain Chassin de Thierry, the battery was intended to protect the harbor of Louisbourg itself. Thus most of the guns were pointing out to sea. Furthermore, during more peaceful times, some of the wall on the landward side had been partially dismantled in order that repairs to the deteriorating stonework could be effected. Interrupted, in all probability by the mutiny, work had never been resumed.

On the 13th of May, William Vaughan, presumably acting on his own volition, had led a force of 400 men through the hills near the town, plundering and burning buildings as they went. Presently, they found themselves in the rear of the Royal Battery. Here they found a large supply of ships' stores which they proceeded to put to the torch. The following excerpt from a letter by an anonymous habitant of Louisbourg best describes the French response:

- At once we were all seized with fright ... and on the instant it was proposed to abandon this magnificent battery, which would have been our best defense, if one had known how to use it. Various councils were held, in a tumultuous way. It would be hard to tell the reasons for such a strange proceeding. Not one shot had yet been fired at the battery, which the enemy could not take, except by making regular approaches, as if against the town itself, and by besieging it, so to speak in form. Some persons remonstrated, but in vain; and so a battery of thirty cannon, which had cost the King immense ' sums, was abandoned before it was attacked.

On the afternoon of May 11, Thierry had sent a note to Duchambon advising that the Royal Battery was in an untenable position owing to the poor condition of the defenses and that the 400 men stationed there would be unable to withstand an assault by the "three to four thousand" soldiers facing them. He advised that the guns be spiked, the battery blown up, and the position abandoned. Incredibly, Duchambon acceded to the last request but, acting under the faulty advice of his engineer, Verrier, would not countenance the destruction of the works. As a result, the cannons were imperfectly spiked, much ammunition and powder was left behind, and the battery was precipitously abandoned on the early morning of May 12.

On the next day, May 13th, a group of about thirteen New Englanders commanded by Vaughan unceremoniously took possession of the Royal Battery after a cautious reconnaissance had revealed no apparent activity. Allegedly, the first of Vaughan's party to enter the battery was a Cape Cod Indian whose name, if he in fact existed, is lost to posterity but whose mettle must have been renowned. Pretending to be either drunk or mad, he crawled through an embrasure and found the place abandoned. The others soon followed. The red coat of one of the soldiers, William Tufts, was said to have been fastened to the flagstaff and hoisted aloft. Thus passed into English possession one of the most renowned bastions of fortress Louisbourg!

Vaughan was soon reinforced by Brigadier Waldo's regiment, and the gunsmith, Major Seth Pomeroy, with the aid of twenty trained men, set about making the poorly spiked cannon serviceable once again. By 10 a.m. the next morning, at least one gun was in working order and began firing upon the town. The Habitant of Louisbourg says, "The enemy saluted us with our own cannon, and made a terrific fire, smashing everything within range." It is claimed that the first shot sent into the town of Louisbourg killed 14 men. Although only four embrasures of the Royal Battery faced the town itself, Waldo decided to concentrate all fire exclusively against Louisbourg rather than the Island Battery, which, along with those batteries of the town that could reach it, made a hot play of cannon fire against the Royal Battery.

While the Royal Battery was being manned and brought into action, the landing of provisions and the New Englander's artillery was taking place at Flat Point. As the artillery was laboriously dragged ashore, the invaders were soon confronted by that factor which had caused the French to believe that Louisbourg was impregnable from landward assault. This factor was mud. The journal of an anonymous New Englander describes the situation perfectly:

- The transporting [of] the cannon was . . . almost incredible labour and fatigue. For all the roads over which they were drawn, saving here and there small patches of rocky hills, were a deep morass; in which, whilst the cannon were upon wheels, they several times sunk, so as to bury not only the carriages, but the whole body of the cannon likewise. Horses and oxen

could not be employed in this service; but the whole was to be done by the men themselves, up to the knees in mud ...

The ultimate destination of these guns was an eminence known as Green Hill which overlooked the walls of the fortress itself. To get to this high point required crossing ground which the French had considered impassable, probably accounting for the failure of the French to fortify this point. The sodden terrain was sufficiently daunting that, if not for the facility of Lieutenant-Colonel Nathaniel Meserve of Moore's New Hampshire regiment, the entire enterprise might have become literally stuck in the mud. A ship-builder by profession, Meserve concluded that the individual cannon could be dragged across the inundated ground on large wooden platforms dragged by men, horses, and oxen. Named "stone boats" after similar platforms used to pick rock from the stony soil of Maine and New Hampshire, these measured sixteen feet long and five feet wide. Buoyed up by the mud, the contraptions proved adequate to the task of hauling artillery across the morass.

The transportation of the artillery to the summit of Green Hill was a rare example of egalitarianism existing between the men and officers with all ranks, including Pepperell himself, having a turn at hauling on the ropes. Within four days, a redoubt made of rockfaced earth with embrasures for six guns was erected. Referred to as the Green Hill battery and mounting two 9-pounder cannon, two "falconets", one 13-inch mortar, one 11-inch mortar, and one 9-inch mortar, its exact location has never been determined. Duchambon stated that it was "on a rise beyond the plains opposite the King's bastion," about 1500 yards away. On May 15, this battery began firing on the fortress. The fire had little effect, however, because of the great distance involved.

After a council of war on the 16th of May, it was decided to move the artillery at Green Hill to another hill northwest of town, closer to the West Gate. It was also decided that eight 22-pounders, two 18pounders, and two 42-pounders from the Royal Battery be mounted there as well. Slowly the noose tightened.

On the 18th of May, Pepperell ordered a general cease-fire. At 11 o'clock, Captain Agnue, accompanied by a drummer and sergeant bearing a flag of truce, stepped forth from the lines of the besiegers and walked through the Dauphin Gate, into the town of Louisbourg. He was met by M. Morpain who blindfolded him and brought him to the office of Intendant Bigot. Here Captain Agnue delivered the following surrender summons, drafted the previous day, to Duchambon:

- [To] the Commander in chief of the French King's Troops, in Louisbourg, on the Island of Cape Breton.

The Camp before Louisbourg, May 7, 1745 [old style]

- Whereas, there is now encamped on the island of Cape Breton, near the city of Louisbourg, a number of his Britannic Majesty's troops under the command of the Honble. Lieut. General Pepperell, and also a squadron of his said Majesty's ships of war, under command of the Honble. Peter Warren Esq. is now lying before the harbour of the said city, for the reduction thereof to the obedience of the crown of Great Britain.

We, the said William Pepperell and Peter Warren, to prevent the effusion of Christain [sic] blood, do in the name or our sovereign lord, George the second, of Great Britain, France and Ireland, King &c. summon you to surrender to his obedience the said city, fortresses and territory, together with the artillery, arms and stores of war thereunto belonging. In consequence of which surrender, we, the said William Pepperell and Peter Warren, in the name of our said sovereign, do assure you that all the subjects of the French king now in said city and territory shall he treated with the utmost humanity, have their personal estate secured to them, and have leave to transport themselves and said effects to any part of the French king's dominions in Europe.

Your answer hereto is demanded at or before 5 o' the clock this afternoon.

W. Pepperell

P. Warren

Duchambon's terse and pithy response was that, until such time as the English army could mount an attack sufficient to convince him of the untenability of his position, his only response "would come from the mouths of the cannon."

Additional batteries appeared in rapid succession around the walls of Louisbourg. In addition to the Green Hill Battery and the Royal Battery, the following batteries are known to have been erected:

- 1. The Coehorn Battery - This battery appears to have consisted initially of 4 @ 22-pounders and ten coehorn mortars. Eventually, two of the 22's burst, to be replaced by 4 more and one 13" mortar which also burst. This battery was located past a pond northwest of the King's Bastion and was considered by Duchambon to be the most dangerous of the batteries because it could play upon the streets as far as the Maurepas gate and the crenulated wall.

2. The Advanced Batteries - On May 25, a battery of 4 guns was emplaced upon a hill about 440 yards from the West Gate. The coehorns and the 9" and 11" mortars were removed from the Coehorn Battery and repositioned to this battery. On May 28, another battery, also referred to as "advanced", was raised nearby. This battery consisted of 2 18-pounders and 2 42-pounders from the Royal Battery. Ultimately, this battery was augmented, on May 31, by the addition of one 18-pounder and two "nine's" in a trench dug at its south end.

3. Titcomb's Battery - Erected on May 31 and located on the northwestern shore of the harbor on heights known to the French as the "Heights of Mortissans", this was commanded by Major Moses Titcomb of Hale's Regiment. It consisted of two 42-pounder cannon, later reinforced by 3 more. It was designed to destroy the West Gate and the Circular Battery of Louisbourg.

During the extensive bombardment of the town, the amateurishness of the besiegers made itself painfully manifest. Ignorant of the niceties of a siege in form as practiced in the 18th century, the New Englanders spurned such ideas as lines of approach, circumvellation, or contravellation, contenting themselves with their unentrenched batteries protected by little more than fascines and loose earth. Noting the destruction to the French works occasioned by a normal load of powder and ball hurled from the maws of their ordnance, a number of enterprising fellows concluded that more havoc might be derived by doubling up on both. This experiment was soon to have unexpected and unpleasant consequences for many an unfortunate gunner. As early as May 5 (old style), one New England soldier wrote in his diary,

- " . . . one Of ye Cannon in our Battery Broke and wounded ye Gunner and 4 men more ... " This same journalist writes on May 13 (old style), "7wo Guns att ye Fa Sheene [Fascine] Battery Burst five men woundd. one his Leg Carry'd away &c. .. ", and finally, on May 19 [old style], he reports, "Above 500 Cannon [balls] fired this Day Several men killd Several woundd. Some killd by Splitting of a Cannon Some Burnt Badly by a barrel of Powders Catching fire."

The journals tell of numerous other fatal incidents. Experience can be a harsh teacher.

The French response to the gradually tightening knot of enemy emplacements was curiously timorous. Although a sortie against enemy besiegers has its incumbent risks, the consequences of idleness under such circumstances could only be worse. Duchambon and his officers, apparently not trusting the loyalty of their men who had mutinied only too recently, attempted only two half-hearted sorties during the entire siege. The intendant, Bigot, writing after the siege had concluded, was in favor of a major sortie against the English. He writes, "Both troops and militia eagerly demanded it, and I believe it would have succeeded."

The first sortie occurred the evening of May 19th when a detachment of unknown, but probably small, size advanced from the fort' with the possible intention of interfering with the creation and reinforcement of the Coehorn Battery.

One New England diarist wrote,

- "in ye afternoon ye Enemy Came out of ye Citty and Ingaged with our men wounded Three of our men But our men Proved too hard for the Enemy and Drove them into ye Citty. "

In any event, this haphazard excursion met with a rebuff. This failure seems to have soured Duchambon and his captains from any additional similar attempts for quite some time.

The second French sortie occurred on May 27 under the command of the Sieur de Beaubassin, a retired officer of Compagnie Franches de la Marine troops, and Jodocus Koller, an elderly sergeant of Swiss troops. For some time a detachment of Provincials, possibly Gorham's regiment, had been occupying the point of land on which a lighthouse was located across the harbor from the Island Battery. The intent was to establish a battery there from which the Island Battery could be bombarded. Duchambon had been informed by a Lieutenant Valle that ten years earlier several 18- and 24-pounder cannon had been buried at the careering wharf (a place where ships were lain on their sides so that barnacles and such could be scraped from their bottoms) to be used as pilings. Fearing that the provincials would find these guns, some of which were still serviceable, and use them against the fortress, Duchambon sent out an expedition of about one hundred militia and privateers under Beaubassin to prevent the establishing of any battery at this location. Unknown to Duchambon, the cannon had already been discovered by the Provincials.

The expedition, loaded into three chaloupes and carrying enough provisions for 10 to 12 days, landed at Grand Lorembec that evening and, in the morning, encountered around 40 Provincials lying in wait for them near the lighthouse. In the ensuing skirmish, the French failed to take advantage of their superior numbers and retreated into the woods losing three men killed and several wounded. This was the last attempt on the part of the garrison of Louisbourg to save itself from the besiegers. The troops on Lighthouse Point were now free to build their battery unvexed from any further sorties from the fort. The only force that could save Louisbourg now would have to come from without, either by sea or by land.

The Capture of the Vigilant

The first major attempt to relieve Louisbourg came by sea. When the French realized that Louisbourg was under attack, a decision was made to dispatch the new 64-gun ship Vigilant under the command of the Marquis de la Maisonfort to relieve the fort. Carrying a crew of 500 and a sizable store of powder and supplies, the ship set sail from Brest with orders to try to make it into the harbor of Louisbourg with her reinforcements and not to expose herself needlessly to capture. On the outward bound leg of his journey, Maisonfort met with good fortune, capturing two British ships upon which he placed prize crews to steer them to Louisbourg.

By the 28th or 29th of May, the Vigilant came within view of Louisbourg. Since the blockading squadron of the British was two and a half leagues or more to the leeward, the opportunity looked good for the Vigilant to sneak into the harbor of Louisbourg unopposed. For some unknown reason Maisonfort did not exploit this opportunity, instead choosing, around mid-day of the 30th, to give chase to the British ship Mermaid (40 guns) which he had spotted. Captain Douglass of the Mermaid, realizing that he was outgunned, fled toward the rest of the British fleet, not yet visible to the French, and kept up a running fight. Soon, the Mermaid was joined successively by the Shirley galley under Captain Rous, then the Eltham, and finally the Superbe under Warren himself.

By 9:00 p.m. and after receiving severe damage plus the loss of 60 men killed or wounded, Maisonfort surrendered his ship. The loss of the Vigilant was a significant blow to the morale of the defenders of Louisbourg. The addition of 64 guns and 500 soldiers would have done much to bolster the defenses of the city. According to one of the besiegers, the Vigilant carried " ... 4 months provision for ye Citty of Louisbourg 300 Souldiers 1000 Barrels of Powdr 20 Brass Cannon Rigging for a 70 gun Ship that is Building att Canady ... ". These supplies, intended for the defense of Louisbourg, were to be turned against it.

Marin's Expedition

The other major attempt at relieving Louisbourg was to come from the landward side. On January 4, 1745, a Lt. Colonel Marin, commanding a mixed force of 500-600 men, had been dispatched from Quebec by the Governor of Canada to attack Annapolis Royal. The plan called for Marin to wait in Acadia at the town of Minas for an anticipated force of two thousand men who were to come from France. This reinforcement was to have been commanded by the Sieur Duvivier, whom we have already met, who had traveled to France to beg for help in carrying out the war in North America.

As late as April, in spite of mounting evidence of an imminent assault upon Louisbourg, Duchambon had instructed Marin to continue with his designs upon Annapolis Royal and that Louisbourg would not require his assistance. Impatient at the failure of French reinforcements to arrive, Marin proceeded unsuccessfully to besiege Annapolis Royal without them. Finally on May 16th, Duchambon realized the inadequacy of his force and sent a messenger to request that Marin march upon Louisbourg with all due haste. On the 24th of May, Marin marched with his force toward Louisbourg.

Through an incredible stroke of luck, the British found out about Marin's relief expedition. An Acadian schooner driven ashore at Lighthouse Point contained a letter from Marin to Duchambon in which the former stated that he was advancing on Louisbourg with a force that, including Indian allies, numbered some 1,300 men. Accordingly Pepperell dispatched a Cruiser and a Rhode Island Brig to Canso with orders to prevent the transfer of Marin's force from the mainland to Cape Breton Island. The ships took the Canso garrison aboard and began patrolling the waters separating Cape Breton Island from the mainland. The British were once again lucky, catching Marin's force in mid-crossing at the Pass du Fronsac. The French, with their army crossing in canoes and whaleboats that lacked any armament above swivel-guns, and without artillery, were no match for the British ships which began to blow them out of the water. Then the Canso garrison, along with a number of friendly Indians, were landed and attacked those elements of Marin's force that had not been in mid-crossing, all the while under the cover of ships' fire. Taken totally by surprise, Marin's force was dispersed and defeated. The few remnants that ultimately made it to Cape Breton Island were too feeble and too late to affect the outcome of the siege.

The Attack on the Island Battery

As early as May 18th, the New Englanders had intended to make an amphibious assault on the Island Battery protecting the entrance to the harbor of Louisbourg. With this strongpoint eliminated, the navy of Admiral Warren would have free rein to enter the harbor and devastate the weakening fortifications of Louisbourg with close range broadsides. For various reasons including high surfs, bright moonlight, fog, and indiscipline and drunkenness among the men, the expedition had been several times postponed. Finally, on June 6th, about 400 men, all volunteers, were assembled for a night attack on the battery. They elected a Captain Brooks to be their commander and set off in whaleboats in the cool and foggy night.

Upon landing, the soldiers were in the process of disembarking from the boats when some less than discrete soul began to shout "Hurrah!" thus alerting the French to the assault. Almost immediately, the poor wretches in the landing party found themselves the targets of shot, musket fire, and langrage (scraps of metal similar to grape-shot fired from cannon). The one hundred and fifty defenders under the commandant d'Ailleboust proved themselves worthy defenders, repelling the invaders, after a fire fight that raged all night, and inflicting 189 casualties upon them. The French had suffered the loss of three men. This was the one signal French victory in the midst of a continually worsening situation.

By June 21st, the New Englanders had completed the construction of their battery at Lighthouse Point, and it opened fire on the Island Battery. Consisting of 6 @ 18-pdr. guns and the "great mortar", the Lighthouse Battery could play on the west platform of the Island Battery, thus preventing the gunners there from firing their cannon. The battery was so well placed that the French could not bring any kind of effective fire against it. Consequently, by the 26th of June, the Island Battery had fallen into shambles and its fire could no longer keep the enemy fleet outside the harbor.

King George's War 1744-1748

- Declaration of War

The Siege of Louisbourg

The Capitulation of Louisbourg

Plans for Further Conquests

The Border Wars

The Peace of Aix-La-Chapelle

Conclusions and Critique

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VII No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1994 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related publications are available at http://www.magweb.com