1744 Campaign In Flanders

Lord Stair resigned as commander of the Pragmatic Army due to his disgust over the internal bickering amongst the allied commanders and for the lack of confidence that the King had shown for any of Stair's strategic ideas. The 73 year old General Wade replaced Lord Stair. In February, an attempted French-Jacobite invasion of England was scuttled by the English fleet and a winter storm. In March, the pretext of fighting as "auxiliaries" to Austria and Bavaria was dropped as Britain and France exchanged formal declaration of war.

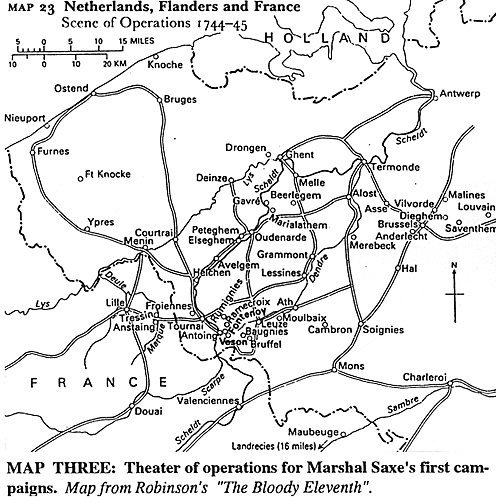

MAP THREE: Theater of operations for Marshal Saxe's first campaigns. Map from Robinson's "The Bloody Eleventh".

In early April of 1744, Marshal Saxe began to assemble a French army of 80,000 men on the northern frontier, between the Scheldt and the Sambre rivers. The allies were still scattered about their winter quarters and could muster no more than 58,000 men (22,000 British; 16,000 Hanoverians; and 20,000 Dutch), hardly enough to defend everything: the border forts, the Channel ports, Brussels, Bruges and Ghent.

Marshal Noailles still retained overall command of the French armies in Europe, and he opened the campaign by capturing Ypres and Fort Knocke, thereby threatening the North Sea ports of Ostende and Nieuport. The Dutch garrisons proved to be too timid and they surrendered their forts at Ypres and Fumes in a matter of days. This was but the first of many examples of deplorable military performance by the Dutch army in the War of Austrian Succession. Simultaneously, Marshal Saxe invested the fortress towns of Menin and Courtrai on the Lys River (see Map Three). The French were now positioned to advance on either Ostende, Bruges or Ghent.

In July, Prince Charles of Lorraine led his Austrian army across the Rhine and occupied a strong position in Alsace. The French sent 26 battalions of infantry and 23 squadrons of cavalry from Flanders to Alsace to stop the Austrian advance. General Wade was urged to take advantage of this temporary reduction of French forces in Flanders, but the opportunity was allowed to slip away. By August, Prussia had renewed hostilities with Austria and the French army in Flanders was brought back up to strength when Prince Charles withdrew across the Rhine to fight the Prussians.

Wade tried to lure Saxe out of his strong position at Courtrai, but when the latter would not oblige, the allies' attentions turned towards the French border fortress at Lille. The Dutch failed to provide Wade with the 10,000 draft horses required to move the seige train and consequently the allied attempt to beseige Lille was meaningless without the threat of artillery. Wade retired back to Flanders in September and made one more attempt to attack Marshal Saxe's position at Courtrai. The Austrians refused to attack and while Wade tried to reason with them, his army was consuming all of the forage between the Lys and the Scheldt.

Wade finally retreated to winter quarters near Ghent and resigned his command in frustration. Saxe finally evacuated his lines at Courtrai on October 9, due to the same lack of forage that bedeviled Wade. However, Saxe made the most of his three months at Courtrai by improving the morale, training and discipline of his army. There would be no more Dettingens in the coming campaigns.

The 1745 Campaign

"The question of the Austrian Succession seems to me to be of secondary importance at the moment," observed France's new military hero, Maurice de Saxe. Indeed, Maria Theresa's claim to the Habsburg domains had been secured by five years of hard fighting. France and Britain were formally at war with one another now and the original cause of war had been forgotten.

The disastrous campaign in Bohemia cured France of any ambitions to the east, and when its pawn, Emperor Charles Albert, died in early 1745, Bavaria was cast aside and left to meet her fate with Austria. French hopes now turned towards the Austrian Netherlands and Marshal Saxe was directed to formulate plans for a major war effort in that country. Saxe had nearly 90,000 troops at his disposal and the majority of these were billeted in Hainault, within easy striking distance of the great border fortresses of Charleroi, Mons and Tournai.

Saxe planned to capture Tournai, located on the Scheldt, and use it as a forward base of operations against Brussels. His spies informed him that the allies would be at full strength in June, so he resolved to lure them into battle on ground favorable to the French, before their reinforcements could arrive. Saxe calculated that the quickest way to provoke a battle would be to threaten one of the border forts. In late April, Saxe made a feint towards Mons and then doubled back to Tournai before the allied army, now commanded by the Duke of Cumberland, could react

On May 17, 1745 Cumberland attacked Saxe's strong position at Fontenoy, some six miles from Tournai, and was repulsed with a great loss of men. A huge column of British and Hanoverain troops almost broke through the French left, but the failure of Prince Waldeck's Dutch troops (who represented half of Cumberland's 45,000 men at Fontenoy) to press home the attack on the French right forced Cumberland to withdraw from the field. Allied casualties exceeded 10,000 killed and wounded, while French losses were at least 7,000, making Fontenoy a horrific battle by 18th Century standards.

Tournai surrended to the French a week later and the whole of Hainault province was now in their hands. Saxe then sent a 5,000 man strike force under the command of the Danish ex-patriot Lowendahl, on a raid to Ghent, deep in allied territory. The surprised garrison surrendered to Lowendahl on July 11th. The daring Dane astounded even Marshal Saxe when he scooped up control of Bruges, Oudenarde, Nieuport and Ostende in quick succession. In three short months, Saxe had established French troops on the shores of the North Sea and the Scheldt, as far north as Bruges and Ghent.

As for the allies, they were in total disarray and it seemed that the entire Austrian Netherlands would fall into Marshal Saxe's hands before the end of the campaign season. The mere mention of General Lowendahl was enough to strike fear into the allied commanders' hearts and whole garrisons were surrendering without firing a shot. By October, the majority of Britain's 22,000 troops in Flanders were back in England fighting the Jacobite Rebellion of 1745. Things looked bleak for the allies and they were about to get even worse in the following year's campaign.

Anglo-French Campaigns Flanders 1741 To 1748

- Background and Outbreak of War

Rhine Campaign of 1743

Campaign in Flanders 1744 and 1745

Campaign in Flanders 1746, 1747, and 1748

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VI No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com