One generally associates the War of the Austrian Succession (1741 -1748) with the battles and campaigns of Frederick the Great of Prussia against the Austrians in Silesia and Bohemia. Historians tend to focus on this theater of war to the neglect of one of equal importance and one involving larger numbers of troops: the Anglo - French conflict in the Austrian Netherlands.

One generally associates the War of the Austrian Succession (1741 -1748) with the battles and campaigns of Frederick the Great of Prussia against the Austrians in Silesia and Bohemia. Historians tend to focus on this theater of war to the neglect of one of equal importance and one involving larger numbers of troops: the Anglo - French conflict in the Austrian Netherlands.

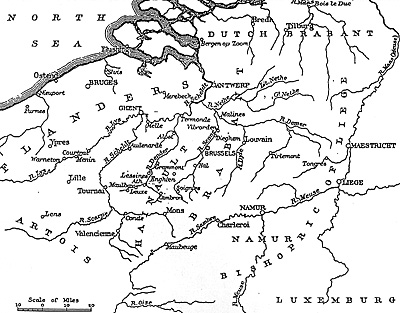

Jumbo Map of Flanders (slow: 155K)

France and Britain were the principal belligerents in this conflict, although Austrian, Dutch, Hanoverian and Hessian troops fought along side the British with varying degrees of effectiveness. The battles were fought over much the same ground as in Marlbourough's campaigns during the War of Spanish Succession (1701 - 1713), but this time the French held the upper hand under the brilliant leadership of their field commander, Marshal Maurice de Saxe. The Austrian Netherlands, comprising modern - day Belgium, was divided into three distinct geographical areas: Flanders, the Brabant and the Bishopric of Leige. (See Map One).

From the British perspective, Flanders was the most important area. It stretched from the North Sea and was bounded by the Scheldt River to the east and extended north from the French border at Dunkirk to the Scheldt estuary near Antwerp. Flanders contained a number of important North Sea ports (Nieuport, Ostende, Bruges and Sluys) that could serve as a base of supply for British operations on the continent or equally as a jumping off point for a French invasion of England. The rich trading city of Ghent was also located in Flanders.

East of the Scheldt River was the province of Hainault, a rich farming area between the Scheldt and Brussels, on the Senne River. The great fortresses at Mons and Tournai blocked any potential French advance on Brussels. Further east was the area of land between the rivers Senne and Dyle known as The Brabant and included the important city of Louvain. Collectively, Hainault and The Brabant formed the heartland of the Austrian Netherlands and the Austrians placed the highest priority on its defense. The Dutch also considered this ground important since it represented the most direct invasion route from France to Holland.

The third geographic area is the Meuse River valley and the area of land east of Louvain. The principal fortress towns in this area were Namur, Leige and Maastricht, all located on the Meuse River (or Maas River to the Dutch). Maastricht was the gateway to Holland, because the Meuse flowed into Holland and was the principal route for transporting goods and supplies from the Austrian Netherlands to the great Dutch trading port of Rotterdam.

A quick glance at the map reveals how geography influenced the fighting in the Austrian Netherlands. The French had one purpose, to cut the British off from their North Sea ports in Flanders and then to drive the allies out of the territory with a thrust down the Scheldt or Meuse river valleys. Any French gains could be secured by building a defensive line along the various rivers that flow from France and into the Scheldt or Rhine estuaries: the Lys, the Scheldt, Dender, Senne, Dyle and the Meuse. Supplies could be easily transported downstream, or north, and return empty upstream to France.

As stated earlier, the allies had differing geographical concerns. The British favored a defense of the North Sea ports plus Bruges and Ghent; the Austrians advocated a defense of. Brussels in the center, while the Dutch were reluctant to commit any troops at all beyond the boundaries of the United Provinces, for fear of giving the French a reason to invade their country. Differing allied objectives did not bode well for cooperation of their military forces in the field.

Marlbourough had been adept at managing his allies in the War of Spanish Succession,but this time, Britain had nobody with the skill and stature of Marlbourough to keep the allies focused on the same objectives. Lord Stair and General Wade tried field command, but both were old men and were not capable of exercising the diplomacy required to bring the British, Austrian and Dutch resources together for a common purpose. King George II's son, the Duke of Cumberland, had the stature, but lacked experience in diplomacy and military affairs. None of these allied commanders would prove themselves capable of matching wits with the French Marshal Saxe.

Outbreak of War

Britain and France were not technically at war with each other until March 15, 1744, though serious fighting would commence during the 1743 campaign along the Main River in Germany. Following Frederick's victory over the Austrians at Mollwitz in 1741, the French diplomat, Marshal Belleisle, toured the courts of Europe and tried to persuade them to renounce the Pragmatic Sanction and to support the candidacy of Elector Charles Albert of Bavaria for the imperial crown of the German states. Prussia, Saxony and Spain fell in with France, while Britain, Hanover and Holland continued to back Maria Theresa of Austria.

Public feeling in Britain favored Maria Theresa and ran contrary to Prime Minister Walpole's pacifistic leanings. The English Parliament voted a subsidy of £300,000 to Austria and pledged to commit 12,000 British troops to the defense of the Austrian Netherlands. King George 11, as Elector of Hanover, went to Hanover to organize his troops in Austria's behalf. France anticipated this move and launched two armies across the Rhine; one to join forces with the Bavarians as "auxiliaries" and march to Vienna, and the other to march to Hanover. Elector George agreed to keep Hanover neutral for one year and to vote for Charles Albert for Holy Roman Emperor, in exchange for French promises to stay out of Hanover.

News of this agreement helped to drive Walpole out of office and the conduct of foreign policy was henceforth administered by the more warlike Lord Carteret. Parliament increased the Austrian subsidy to £500,000 and voted to send 16,000 British soldiers to Flanders to serve as "auxiliaries" to the Austrian army. Command of the British forces was given to the 70 year old Lord Stair.

By the summer of 1742, Lord Stair had received permission to land his troops at Ostende. He tried to persuade the Dutch to furnish "auxiliaries" to the Austrians, but they would have none of that for the time being. Following Frederick's victory over the Austrians at Chotusitz, Maria Theresa was persuaded to make peace with Prussia to save the rest of her country. The Treaty of Breslau freed up Austrian troops to drive the French out of Bohemia (Prague) and the Danube river valley.

In September 1742, the French army in Westphalia under Marshal Maillebois was called on to rescue Marshal Broglie's army in Prague. The road was now clear for the Hanoverian army to join forces with the British and Austrians in Flanders. Lord Stair proposed a bold plan to attack Dunkirk and march on towards an undefended Paris. The plan had merit, but disagreement amongst Stair, General Wade and King George prevented anything from happening before the coming of winter. So closed the 1742 campaign.

Anglo-French Campaigns Flanders 1741 To 1748

- Background and Outbreak of War

Rhine Campaign of 1743

Campaign in Flanders 1744 and 1745

Campaign in Flanders 1746, 1747, and 1748

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VI No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com