Lord Stair presented several proposals to King George for an invasion of France via the Moselle River valley in 1743. However, the Austrians prevailed on the King to join them in a demonstration of force in the Rhine valley to win support among the local principalities. Stair drew up plans to move his "Pragmatic Army" of British, Austrian and Hanoverian troops to Mainz. By early May 40,000 allied troops were in the vacinity of Frankfort and George II was on his way from Hanover to take personal command of the army.

Lord Stair presented several proposals to King George for an invasion of France via the Moselle River valley in 1743. However, the Austrians prevailed on the King to join them in a demonstration of force in the Rhine valley to win support among the local principalities. Stair drew up plans to move his "Pragmatic Army" of British, Austrian and Hanoverian troops to Mainz. By early May 40,000 allied troops were in the vacinity of Frankfort and George II was on his way from Hanover to take personal command of the army.

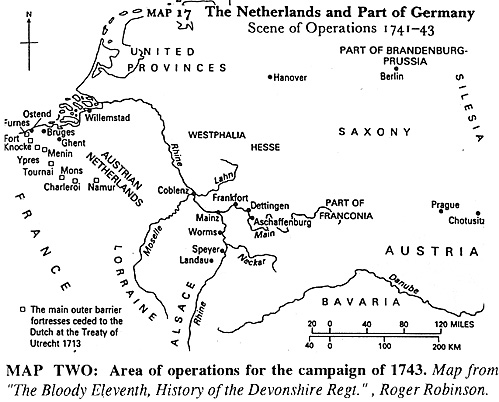

MAP TWO: Area of operations for the campaign of 1743. Map from "The Bloody Eleventh, History of the Devonshire Regt.", Roger Robinson.

The nearest French army belonged to Marshal Noailles, encamped at Worms, forty miles south of the allies (see Map Two). The allies had a vague plan to separate Noailles from the Bavarians and so they made a liesurely crossing to the south bank of the Main River on June 3, 1743. Noailles crossed the Rhine with 60,000 men and headed in a northerly direction towards the allied bridgehead on the Main.

During the next couple of weeks, Stair recrossed the Main and found himself completely outmanoevered by Noailles. The Pragmatic Army had ventured up the Main as far as Aschaffenburg to secure supplies, but Noailles anticipated this move and beat him to the spot. Cut off from their supplies in Franconia, the allies had no recourse but to retreat back down the Main to their supply base at Hanau. Again, Noailles anticipated this move and he detached his nephew, the Duc de Grammont, with 30,000 men to block the retreat of the Pragmatic Army . Grammont crossed the Main at Seligenstadt, some three miles in front of the allied army and took up a strong position near the town of Dettingen.

The Pragmatic Army was caught in a bottle: Grammont was in front of them, Noailles was in their rear, and the heavily forested Spessart Hills blocked any movement to the right. The Main River was on the allied left, but Noailles had positioned a number of artillery batteries on the French side of the Main and these guns poured a deadly enfilading fire into the Pragmatic Army as it marched along the river bank.

There was nowhere to go but forward and the impetuous Grammont surrendered his tactical advantage by abandoning his strong defensive position and advancing forward to attack the allies as they deployed for battle. In the ensuing fight, the British cavalry got the best of the elite French Household Cavalry (Maison du Roi) while British musketry mowed down the Gardes Francaises and other French line battalions. Out of 35,000 engaged, the French lost 6,000 killed and wounded, including hundreds of Gardes Francaises, who drowned while attempting to swim the Main in their retreat. The allies numbered 40,000 men and they suffered some 2,400 casualties

The French War Minister, the Comte d'Argenson, turned command of the army over to Maurice de Saxe, who was seen as the only general capable of rebuilding the shattered French army. As we shall soon see, this appointment would have a profound and positive effect on the French war effort in the Austrian Netherlands. For all intents and purposes, the campaign of 1743 ended at Dettingen. French forces in Bohemia and in the Danube valley were chased back across the Rhine by the Austrians and it became clear to both sides that the focus of attention would return to that familiar battleground of the Austrian Netherlands.

Anglo-French Campaigns Flanders 1741 To 1748

- Background and Outbreak of War

Rhine Campaign of 1743

Campaign in Flanders 1744 and 1745

Campaign in Flanders 1746, 1747, and 1748

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. VI No. 3 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1993 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com