Contact was finally made with Elphinston and Richmond on July 25. Intrepid and the ten transports were then escorted back to Havana, eventually arriving there on July 28. Richmond collected three transports and returned with them and Echo (28), Cygnet (16) and the bomb ketch Thunder to rescue the 594 stranded men. Richmond and Cygnet and the three transports returned to Havana with the rescued men on August 10 while Echo and Thunder sailed further eastward into the channel on the lookout for the second division. [157]

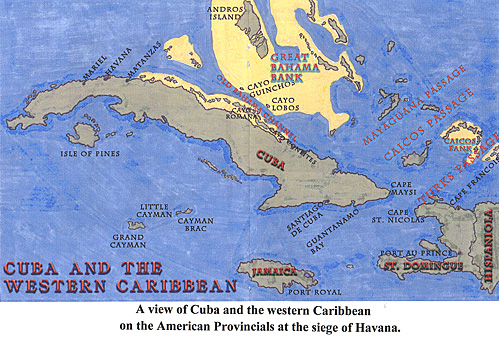

If the passage of the first division had proven an ordeal, the journey of the second division was a nightmare. In the afternoon of July 21, as it sailed through the Caicos Passage at the southeastern end of the Bahama Islands, it was attacked by a French squadron composed of Diademe (74), Brillant (64), the frigate 1'Opale (26), and six armed brigs and schooners that had left Cape Francois two days earlier under the Chevalier Fouquet, Blenac's second in command. Choosing not to fight against superior numbers, the convoy's commander, Capt. John Houlton of Enterprise, gave the signal to disperse and to assemble at the predetermined rendezvous off Cape St. Nicolas.

Aboard the transport Delaware Major Joseph Gorham described the chase: "the Transports on which the Corps of Rangers were on board, escaped very narrowly and by being only about common shot to the windward, and a little ahead of the enemy with night to favor us. We were soon a lone ship, and ...however proceeded to our place of Rendezvous..." Most were saved only by the arrival of night but others were less fortunate. The transports Pelling, Britannia, Betsy & Sally, Nathaniel & John, and Hopewell were captured with 92 men of the New York Regiment and another 396 of the 58 Regiment

aboard. [158]

Reduced to a total of 832 men aboard nine transports and their three escorts, the division regrouped and resumed its journey towards Havana entering the Old Bahama straits. It was eventually found by Echo and Thunder and escorted through the channel without further setback arriving at Havana on August 5.

The troops of the North American contingent landed at the climax of the campaign against Havana. By the end of July the British army was understrength and ravaged by disease and Albemarle noted on July 25 that "The North Americans would greatly facilitate this business." However, on July 30, just two days after the arrival of the bulk of the first division, the outcome of the siege was decided at El Morro, not by the newly arrived provincials, but by 581 picked men of the 1st, 35th, and 90th Regiments who assaulted it an took it by storm. Instead, the Americans were deployed to the West of the city, a position that involved mostly the passive role of cutting the city off from its water source and resupply, and from which they participated only in a few skirmishes. On August 11, one day after the arrival of the marooned contingent of the first division, the city was forced to capitulate because British artillery superiority threatened to reduce the city to rubble.

After the surrender the provincials were mainly employed in the dismantling of the British batteries used in the siege against El Morro. In spite of their failure to directly participate in the decisive operations at the end of the campaign, their contribution to the effort was crucial. Pocock remarked that "...it was a great satisfaction both to Lord Albemarle and me that so many of the reinforcement arrived in perfect health. They were much wanted as not only the army but like wise the fleet were extreme sickly."

The arrival of 3,409 fresh troops provided a psychological boost at just the right moment to an army that was on the edge of exhaustion and that for two months had been continuously shrinking in size and strength. But more importantly they provided Albemarle with the manpower needed to occupy the extensive area surrendered with the city of Havana which included the city and port of Matanzas 15 leagues to the East and the town and port of Mariel 7 leagues to the West.

The provincials' limited involvement would not spare them from suffering casualties. As early as August 6 Albemarle observed: "The reinforcements from North America have been landed ... they begin already to fall sick." The low lying, marshy coastal area West of Havana where they were posted was a haven for the Aedes Aegypti mosquito carrying the yellow fever virus. The disease was soon decimating their ranks with the same virulence as it had those of the earlier arrivals. [159]

Chaplain John Graham of the Connecticut regiment described the woeful condition of the American troops by September 29 in his journal as: "wasted with sickness: their flesh all consumed, there bones looking thro the skin, a Mangie and pale countenance, Eyes almost Sunk into there heads, with a dead and downcast look - hands weak, knees feeble, Joints Trembling -- leaning "...upon staves like men bowed and over loaded with old age, and as they Slowly move along Stagger and Real, like Drunken men - pityfull objects." [160]

The Secret Committee's ambitious plan envisioned that, after the expedition against Havana had succeeded, Albemarle was to return to Amherst all of the troops of the North American contingent plus others to form a corps of 8,000 men that would be used to conduct a further campaign against Louisiana. As early as August 18 Albemarle had to admit to Amherst that: "I am so little able to send a reinforcement to assist you in your undertaking, that for the present I must detain the troops Brigadier Burton brought here till I see what force is necessary for the defence of this island. For the present, you must expect no assistance from us because we have none to give you." Pocock concurred: "The fleet and army are so much reduced by sickness - the unhealthy climate has brought on this, with the necessary fatigue of so long a siege, that Lord Albemarle and I agree in opinion no further operations can possibly be carried on this season."

Of the total 16,035 regulars and provincials that had come ashore during the siege, 1,790 died up to the surrender of Havana on August 11. Of these, 606 died in combat, 130 were missing, and 1,054 died from disease. By October 8 the army's losses just from disease had increased to 4,708, or about one third of the force, and of the remainder only 2,067 rank and file were fit for duty. The Royal Navy had lost 86 in combat and about 1,300 to disease of which about 800 were seamen and 500 were marines. As the fever spread and the losses grew Albemarle's desperation rose and he had to report to Lord Egremont that: "...if the great mortality and encreasing sickness does not stop I shall rather want Troops than be able to send any away." Havana had been taken, but at a high price. When he heard the news in London Dr. Samuel Johnson grumbled: "May my country be never cursed with such another conquest!"

The 40% casualties suffered by the Connecticut Regiment reflect the overall average rate of loss of the North American brigade by October. Only 683 of the original 1050 Connecticut men boarded transports back to New York but another 46 died at the military hospital at Staten Island. The Rhode Island Regiment fared even worse. Of their original 212 men 112 died (a 53% casualty ratio), 110 from the fever and only 2 from combat. Gorham's Rangers were reduced by disease from 253 men to 151 and had to be disbanded. Fevers also slashed the New York Independent Companies from 335 men to only 101 fit for duty. The remaining Rangers and Independents were incorporated by Albemarle into his own depleted regiments and the surviving officers were sent back to New York to recruit anew. With 396 of its 590 men captured at sea, the 58th Regiment ceased to be viable unit and was disbanded at Havana. [161]

In spite of the shortages of manpower, Albemarle resolved to send at least the provincials of the North American brigade back to America by the middle of October. They began to embark on October 10 and sailed towards New York on October 19 under escort of Intrepid with these weakened battalions aboard:

They arrived at New York at the end of November. The crossing was without incident, but about a quarter more of the men died during the voyage from the fever. For many more, leaving the island and reaching the safety of home would not guarantee survival. Those infected men who survived the crossing were treated at the military hospital on Staten Island, New York where they continued to die in alarming numbers. Even the change in weather did not prove beneficial. Lt. Col. Patrick Mackellar, Chief Engineer of Albemarle's army, noted: "a long and severe winter had such an effect upon soldiers almost exhausted by an active campaign in a very warm climate that very few of them lived to see the spring."

Army surgeon John Adair attending the stricken provincials found "many of them so ill that they cannot Recover and many of the Rest in a very Dangerous Way." The price paid by the 1,959 provincials who landed in Cuba had been high. Not even counting those who died in the hospital after the end of the campaign or those who survived only to remain physically incapacitated, the losses exceeded 50% of the original force.

A calamity of this magnitude shocked opinion in the American colonies and overwhelmed any sense of accomplishment derived from participating in an important victory. To the rank and file provincial the campaign had been anything but an adventure of conquest in an exotic land. Instead, a perilous sea voyage had exposed them to shipwreck and imprisonment. The breakdown in communications had prevented a timely departure causing an arrival so late as to almost make their role superfluous. But, worst of all, they had been annihilated in the most inglorious manner by an unseen adversary only to be discharged and be sent home forgotten, discarded like the refuse of British imperial ambitions. [162]

The repercussions of the debacle went beyond the personal considerations of the individual provincial soldier. Keen observers like Benjamin Franklin challenged the very relationship of the American subjects to the King when he questioned the benefit to the colonies of serving England in these enterprises. He found the fall of Havana to be "...a conquest of great importance; but it has cost us dearly, when we consider the chaos caused by disease in our brave little army. I hope that the peace treaty will provide us some advantages in trade or possessions to offset the great losses suffered in this enterprise." [163]

With the Peace of Paris treaty returning Havana to Spain in July of 1763, any gain to the American colonies was short lived and the sacrifice of the provincials appeared even more futile. The only benefit that they would derive from this service was the military training that they put to good use when they mustered again in 1775 as members of the Continental Army taking the field against the very sovereign they previously fought for.

It has been suggested that the loss of so many men at Havana played a part in the England's eventual loss of the American colonies. One scholar [164]

argues that "...when Pontiac's Rebellion broke out in 1763 it could not be quickly suppressed because a large part of the army was still suffering from disease contracted at Havana. The failure to deal promptly with Pontiac's rebellion was one of the major reasons for the Greenville's ministry's decision to reorganize the British military establishment in America, which in turn set in motion the events which led directly to the American Revolution. The British took Havana and gained the Floridas, but at the cost of an army, and perhaps unknowingly set the stage for the loss of an empire."

1st Connecticut Provincial Regiment 683

New York Provincial Regiment 343

New Jersey Provincial Regiment 149

Rhode Island Provincial Regiment 97

Total 1,272

American Provincials at the Siege of Havana

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XIII No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com