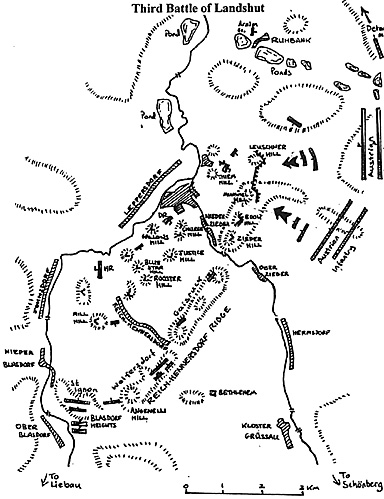

The importance of Landshut was now clear and for the next three years its defense was entrusted to Henri Auguste Baron de la Motte Fouque (1698-1774), a Prussian general of Huguenot descent who had already fought in another skirmish there as the Prussians recaptured the town on 22 December 1757. Fouque was, by all accounts, a rather disagreeable gentleman, but he was extremely diligent in carrying out his task. His corps was too small to protect the area effectively and was always subject to sudden changes in composition as Frederick recalled elements to meet emergencies elsewhere. Fouque did his best to compensate by fortifying the position, constructing a network of over ten forts on the hilltops outside the town in 1758. The most extensive of these entrenchments stretched from Leuschner Hill to Mummel Hill, with a small redoubt on the latter and a further one on Book Hill just to the south.

A string of three small fleches extended this line southwards to Zieder Hill, while a star redoubt capped Thiem Hill to the west. The heights south of the town were also fortified with another large entrenchment on Church Hill and a series of smaller ones across Gallows and Justice hills. Further positions covered Blue Star Hill and Rooster Hill, with another line of small entrenchments on the ridge of Mill Hill in a line south of Reich-Hennersdorf. These positions were to receive their first major test in 1760.

The year 1759 had ended with a string of disasters for the Prussians and Frederick had great difficulty scrapping together an army for the following year. He commanded the main force of 50,000 in Saxony with his brother Prince Henry and a further 35,000 deployed at Sagan in the east to watch for the Russians. General Stutterheim and another 6,500 were posted opposite the Swedes in Pommerania, while Fouque was given a field force of 14,500 to hold the Landshut area. The main Austrian army totalled over 78,000, most of whom were concentrated near Dresden under Marshal Daun with a detached corps under Lacy pushed out towards the river Elbe and another at Zittau under Beck. While Daun waited for the Army of the Empire (22,500 men) to arrive from quarters in Franconia, another 45,000 men were sent under Feldzeugmeister Gideon Ernst Baron Loudon (1710-90) to invade Silesia.

Owing to the Prussian position at Sagan which blocked the Russian advance and prevented direct cooperation through eastern Saxony, Loudon decided to attack via Glatz instead. The commandant of Glatz sent urgent messages in late May that the Austrians were now pouring across the frontier into central Silesia. Fearing for the fortresses, Fouque abandoned Landshut and headed for Schweidnitz. As soon as he was gone, Loudon sent a detachment to seize the magazine there and then pulled his forces back to besiege Glatz. Minister Schlabrendorff urged Fouque to retrace his steps and recapture the valuable town.

As other orders arrived from Frederick who was also displeased by the precipitous retreat, Fouque had no choice but to head back for the mountains. He arrived on 17 June, driving out the Austrian detachment there under Feldmarschallleutnant Count Gaisruck who retired to the Reich-Hennersdorf ridge.

Fouque hastily repaired the entrenchments the Austrians had partially demolished and settled down to wait for reinforcements before pressing on to relieve Glatz. He decided to occupy the entire extent of his fortified line, despite the fact that it stretched for nearly 6 km. To make matters worse, he had to detach Maj.Gen Zieten with four battalions and two hussar squadrons to hold the Zeisken Berg hill on the vital road back to Schweidnitz. This left him only about 12,000 men to defend his extended position: Frederick later reckoned that this was only about a third of the number necessary.

As soon as Loudon heard that Fouque was back, he left 4,000 men to blockade Glatz and marched with the remaining 40,000, hoping to surprise him and capture his entire force. Reinforcements were sent under Feldmarschal- leutnant Wolfersdorff join to Gaisruck on the Reich-Hennersdorf ridge to keep Fouque pinned behind his entrenchments facing south while the rest of Loudon's men moved quietly up from Glatz to camp at Schwarzwaldau in the hills to the east of Landshut. General Beck was also requested to send a detachment from his positions near Zittau to close in from the west, while Jahnus, who was again in the area, was sent to neutralize Zieten on the Zeisken Berg and cut the line of retreat.

During the night to 23 June Loudon's men moved into position on the high ground north of the Zieder stream. Eight battalions were posted on the hills to the north and east of the big entrenchment on Leuschner Hill covering gun batteries that enfiladed the Prussian right. Loudons cavalry sheltered in the wooded ground behind these infantry, while the bulk of his foot took position on the slopes opposite Mummel Hill. Gaisruck and Wolfersdorff continued to line the Reich-Hennersdorf ridge with ten squadrons and eight battalions, including the two of Simbschen's regiment. General St Ignon and another five battalions and two cavalry regiments held the heights of the Blasdorf defile on the Liebau road.

The attack began at 2am on 23 June with the main assault hitting the entrenchments on the Leuschner and Mummel Hills held by Infantry Regiment Fouque under Colonel Baron Rosen, and the first battalion from Regiment Mosel. A secondary attack was launched from the Reich-Hennersdorf ridge against the positions on Mill Hill and the heights to the south defended by three free battalions, one of grenadiers and the Werner Hussars. The rest of the Prussians were entrenched on the heights immediately south of Landshut, with one free battalion and two companies from the Fouque regiment in the town itself. The Malachowski Hussars were in reserve behind Book Hill, with part of the Platen Dragoons and a garrison battalion positioned behind Leuschner Hill. Grenadier Battalion Arnim was detached in the valley by the hamlet of Ruhbank, covering the escape route north.

Heavy fighting ensued as the Prussians fiercely contested every hilltop, retiring from one position to the next, firing as they went. The situation got desperate as Fouque spotted the Austrian cavalry moving to cut the road north of the town. Major von Owstien managed to break over the Bober with 900 cavalry and escape westwards via Kupferberg to reach Breslau. Fouque collected the remnants of the infantry, brought them across the river to Leppersdorf and placed himself at the head of a square formed by volunteer battalion Below. The Austrian cavalry closed in and repeatedly summoned him to surrender. Each time he answered with a hail of bullets, until his men were finally scattered, his horse shot under him and himself wounded three times.

His conduct and that of his men spared him the wrath of the king who subsequently praised his defeated troops, comparing them to the ancient Spartans. No less that 27 officers and 1,900 men had been killed and a further 8,051 captured along with 34 flags, two standards, the silver kettledrums of the Platen Dragoons and all but one of the 68 cannon. Around 1,100 infantry and artillery had got away in addition to the 900 cavalry, while Zieten's detachment managed to leave the Zeisken Berg in time and escape to Schweidnitz.

The fact that the Austrians lost 2,918 men is a further indication of the Prussians' stiff resistance. The same could not be said for the garrison in Glatz to which Loudon turned after his victory, for it mutinied and surrendered without significant resistance on 26 July. The worsening situation in Silesia caused Frederick to abandon the siege of Dresden and head eastwards, redressing the situation in his victory over Laudon at Liegnitz on 15 August.

Conclusion

The Austrians did successively better in the three engagements, scoring a decisive tactical victory over the Prussians in the last which had some impact on the wider strategic situation. All three actions posed considerable problems for commanders on both sides. The dictates of geography and strategy placed the Prussian entry point at the northern end of the area, facing Austrian forces to the south and east. Though not impassable, the Bober acted as the western boundary on all three occasions, with the fighting taking place on and around the hills east of the river. Though Landshut was ringed by hills, these were surrounded in turn by more high ground.

The long Reich-Hennersdorf ridge was too far from the main position to be held by the Prussians defending the town in 1745 and 1760 and so served as a convenient screen for the Austrian deployment. The heights to the south and north of the town also faced further hills which served as collecting points for the Austrian attacks, notably the high ground by Reich- Hennersdorf itself.

Nonetheless, it was difficult to deploy from these heights as the Austrians discovered in 1745, especially as the Prussians were defending a more compact position centering on Justice Hill closer to the town. When the roles were reversed in 1757 the ground decisively favored the Austrians as the Prussians had to approach Landshut up the cramped Bober valley from the north. Here, the Austrians could not only deploy on the heights immediately north of the town, but on those flanking the valley to the east, forcing the Prussians to operate on the difficult ground closer to the river. Nonetheless, the Prussian assault up Book Hill came close to success, indicating the relative flexibility of 18th century line troops who were clearly capable of fighting in such difficult terrain.

Sources

The most detailed published account of First Landshut is in the Prussian General Staff history of the Second Silesian War (Der Zweite Schlesische Krieg 1744-1745, 3 vols., Berlin, 1895), which can be supplemented by the briefer Austrian account in the history of the War of the Austrian Succession published by the historical section of the Austrian War Archives (Oesterreichischer Erbfolgekrieg 1740-1748, 9 vols. Vienna, 1896-1914). There are no such accounts for the other two battles, but the Prussian perspective is given in the General Staff history of the Seven Years War (Der Siebenjahrigen Krieg 1756-1763, 12 vols. Berlin, 1901-13).

Other useful sources include:

J.W. v. Archenholz, Geschichte des Siebenjahrigne Krieges (Berlin, 1828)

Andrew Bisset (ed.), Memoirs and papers of Sir Andrew Mitchell K.B. 2 vols.

(London, 1850)

Frederick the Great, Geschichte des Siebenjahrigen Krieg (various editions)

Curt Jany, Geschichte der Preussischen Armee vom 15. Jahrhundert bis 1914 4

vols. (reprint Osnabrock, 1967)

More Landshut

-

Introduction

First Landshut: 22 May 1745

Second Landshut: 13-14 August 1757

Third Landshut: 23 June 1760

Orders of Battle

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. XI No. 4 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by James J. Mitchell

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com