[The following is an excerpt from Christopher Duffy's book 'Russia's Military Way to the West "]

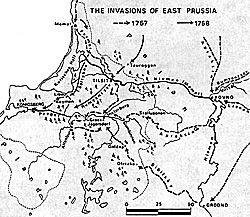

Map depicting Russian troop movements prior to the

battle of Gross Jagersdorf. Courtesy of Christopher Duffy,

from "Russia's Military Way to the West."

Map depicting Russian troop movements prior to the

battle of Gross Jagersdorf. Courtesy of Christopher Duffy,

from "Russia's Military Way to the West."

Frederick of Prussia lived in fear of any Russian intervention in Western affairs, yet he was strangely willing to lend credence to anything that people had to tell him about Russian extravagance, corruption and muddle. Such reports had come from the diplomats Vockerodt and Mardefeld, and from his bosom friend Winterfeldt, who had seen the Russian army in 1741, when it was still in a bad way after the Turkish war. Keith's expenence of the army was more recent, but when, shortly before the Seven Years War, he ventured some words of praise of the Russian troops, Frederick rejoined, 'the Muskovites are a heap of barbarians. Any well-disciplined troops will make short work of them.'

As we have seen, Frederick the Great opened the Seven Years War in the south by invading Saxony, but the winter of 1756-57 found the Russian infantry still accumulating in crowded and dirty quarters in Livonia, and the wretched cavalry trailing up from the interior of Russia In February 1757 the government heard with despair that General Apraxin was still unable to march.

Ready or Not

Ready or not, the Russians were galvanised by the news that their Austrian allies had been defeated by Frederick at Prague, and finally towards the end of May 1757 the green columns set out from the Dvina in a generally westerly direction. The commands of Apraxin and Rumyantsev reached Viliya opposite Kovno in the middle of June, but in the absence of a bridge the whole force had to be ferried across the river on two boats - the consequence of the 'dire disorder and terrible confusion which dominates everything that relates to the Russian army' (quoted in Frisch, 1919, 28).

Eleven thousand men had already fallen sick, and the difficulties of supply were augmented when the army could no longer avail itself of the facility of transport on the Viliya and Niemen, but had to strike across the marshes and woods of Polish Lithuania, losing contact with the chain of magazines that stretched back to the Russian Baltic provinces and the Ukraine.

A spell of rain gave way to a period of intense heat that was to last through the summer, and return in almost every campaign season of the Seven Years War. Weyrnarn writes that the result was a greater mortality still, for 'the ordinary soldier is tormented with heat under his covering of sweat and dust, and common experience shows that no force of punishment is capable of preventing him from drinking hard and long of the stinking, foul and muddy water, and letting it pour over his body' (Weymorn, 1794, 26-27).

The strategic objective was to reduce the sizeable enemy province of East Prussia, which was weakly held by Field Marshall Lehwaldt with 32,000 troops and militia, and conveniently isolated by the "Polish Corridor" from the rest of the King of Prussia's states.

In August 1757 the Russian host at last crossed into Prussian territory, and the cavalry began to spread out. Like the soldiers described in Solzhenitsyn's 1914, the Russians of 1757 gazed in wonder at the almost inhuman cleanliness of the landscape and the villages. Apraksin sought to maintain good order, but the Cossacks gave a lead in rapacity and vandalism to even the best regiments of the army. The movement as a whole resembled an emigration of nomadic barbarians. Apraksin never bothered to sound the way ahead, and in this example the generals followed him religiously. All of this was to have dire consequences for the outcome of the campaign, and for the West's impression of the Russian army in the Seven Years War.

At Kovno

At Kovno Apraksin had been joined by two southerly columns, and at Insterburg he was met by the light corps of Sibilsky, and the 1 6,000-strong detachment of Fermor, who had reduced the little port of Memel after a brief bombardment.

Finally, by the last week of August the movement coalesced into a single thrust north of the Masurian Lakes in the direction of the provincial capital of Konigsberg. Apraksin was disturbed to learn that an enemy army under Lehwaldt was somewhere in the offing, but the Prussians were decidedly inferior in numbers, and the constant daily false alarms from the Cossacks had succeeded in breeding attitudes of 'false security and contempt for the enemy' (Weymarn, 1794, 95).

The 29th of August found the army short of fodder, and moving irresolutely just south of the Pregel in a terrain of marshy streams and stands of dense woodland. There was precious little space to draw up the regiments in order, if it came to a fight, and the ailing Generalanshef Yurii Lieven urged Apraksin to hold the troops overnight in a precautionary battle position in the clearing of Gross Jagersdorf. Generalanshef George Browne supported this opinion 'with his usual violence and impetuosity' (Weymarn, 1794, 90). Apraksin rejected these ideas, and under the influence of Fermor he brought the army back for the night to the site of the last camp, where the troops could eat and rest. The army slept well.

Early on 30th of August

-

a purple glow suffused the horizan, foretelling a splendid day.

The mist had set in heavily before dawn, but now it began to thin

out, and the air became clear and transparent. The sun, rising

above the hills, had aIready lit the whole horizon when the

sonorous signal of cannon fire broke our sweet slumbers, and

set the whole army in movement . (Bolotov, 1870-73, I,

517).

At about four in the morning the army got once more to its feet and began to shuffle around the east flank of the wood of Norkitten, with the leading elements striking south in the direction of Allenburg and a region of temptingly untouched pastures and barns.

Sibilsky got successfully under way with an advance guard of 10,000 men (4,000 cavalry and 15 battalions of infantry). The main body was supposed to follow in two parallel columns, but in fact the appointed right-hand column (the First Division, under Fermor) was still sorting itself out behind the wood of Norkitten, and the stout and comfortable Generalanshef Vasilii Lopukhin emerged alone into the clearing with his Second Division.

By the scheme of things the Second Division was supposed to stand in the rearward line in any engagement, and Lopukhin had been forced to yield up his field artillery to the advance guard and the First Division. He retained only his regimental artillery and a complement of secret howitzers, and Fermor told him that even these were unnecessary, 'since your force is tucked away as securely behind the First Division as if you were sitting in your mother's lap.' (Weymarn, 1794, 93). A Third Division under George Browne was to follow up behind and cover the general baggage of the army.

Such was the state of affairs when the little Prussian army erupted into the scene from the west. Lehwaldt had just 24,700 men to pit against the mass of 54,000 Russians, but he threw his force into the attack in unthinking obedience to King Frederick's orders.

More Gross Jagersdorf

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal Vol. X No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Seven Years War Asso. Journal List of Issues

Back to Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by James E. Purky

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com