Soult's Last Stand

Toulouse 1814

Well done, the Eighteenth...

by Leon Parte, France

| |

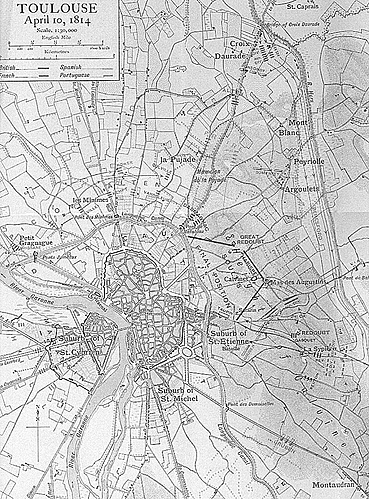

On the 8th the 18th Hussars made a brilliant dash at the bridge against the French dragoons, after a pause on both sides. Jumbo Map of Toulouse (monstrously slow: 516K) The Allied infantry began to advance and this set the cavalry off. The trumpets rang out the charge together; but the British Hussars were too sharp for the brass helmets, and jamming the dragoons between the stone parapets, broke them after a moment's sabring, and spurred over in pursuit led by Major Hughes, Colonel Vivian being incapacitated by a carbine bullet. Pierre Soult who was commanding the French Cavalry in person at this point, narrowly escaped capture in the ensuing rout. The 18thpursued until they came under the French guns, when they returned in good order having taken some 120 prisoners and inflicted scores of casualties. This action, costing just 15 Hussar casualties stopped the French from blowing the bridge and thereby preventing the union of the two wings of Wellingon's Army. As Wellington was reported to say “Well done, the Eighteenth; by God, well done!” Wellington wished to attack on the 9th, but owing to the removal of the pontoon bridge closer to Toulouse, it was necessary to postpone until the day after. The Allied army occupied a peculiar position, and one that indicated in a marked degree the place Napoleon had won in the hearts of his people. In the north, where the population had suffered more severely from the ravages of war, from the conscription, and the devastating passage of troops, the peasants rose and helped the tottering emperor. However, in the hot, impressionable south they not only refrained from armed resistance, but welcomed the “perfidious” English; and Soult, fighting a last battle for the cause, fought it unaided by his countrymen, who were even reluctant to help him dig his trenches, probably having more sympathy with the success of the invaders than with that of the bayonets that upheld the Tricolour. The weather had improved a little, but there was still much water out over the country, and the, Garonne, flowing swiftly in a deep channel, threatened the Allied pontoons as it foamed on its way to the Atlantic. Wellington's Plan Wellington's plan, the result of personal observation carefully carried out during the previous days, was to deliver two feint attacks, one by Sir Rowland Hill against St. Cyprien across the Garonne. The other against the outposts along the canal north of Toulouse under Picton, while Freire's Spaniards carried the isolated hill of Pugade, and Marshal Beresford stormed the French right on the hilly platform of St. Sypière, the cavalry moving along each side of the Ers to watch Berton whose horsemen roved over the marshy fields before and beyond St. Sypière. At two o'clock on the morning of the 10th April the allies mustered under arms in the darkness, and the hussars passed to the head of Beresford's columns, which they were to precede on their hard two-mile march along the front of the enemy's position. After many halts, until everything was in proper order, the army set out at about six o'clock, and with the sun shining on its war worn ranks, stepped boldly forward to begin this useless and unnecessary battle. Hill’s Attack While Hill began his attack against St. Cyprien, and Picton, seconded by Baron Alten, opened on the French skirmishers in front of the canal. The Spaniards advanced under a fire from two guns and quickly took possession of the Pugade, St. Pol having orders to fall back to the Calvinet, the first of those two platforms which formed the main strength of Soult's position. Meanwhile Beresford, leaving his clattering batteries in the village of Monblanc, turned to his left, and soon clearing the protecting barrier of the Pugade, marched ahead under a terrible flank fire between the platforms and the river. Advancing in three columns through the swamps, the heights on their right became alive with smoke and flame, and we learn from the journal already quoted that the men had to run by companies to escape the fire, the soft mud having one advantage--that it put out the falling shells, and when a round shot struck it did not rise again. Part of the action is described by a soldier of the 71st in his Journal:-

At this moment of helplessness the French came up. One of them made a charge at me, as I sat pale as death. In another moment I would have been transfixed, had not his next man forced the point past me: 'Do not touch the good Scot,' said he; and then addressing himself to me, added, 'Do you remember me?' I had not recovered my breath sufficiently to speak distinctly: I answered, ' No.' 'I saw you at Sobral,' he replied. Immediately I recognised him to be a soldier whose life I had saved from a Portuguese, who was going to kill him as he lay wounded. 'Yes, I know you,' I replied. 'God bless you!' cried he; and, giving me a pancake out of his hat, moved on with his fellows; the rear of whom took my knapsack, and left me lying. I had fallen down for greater security. I soon recovered so far as to walk, though with pain, and joined the regiment next advance." Still the 4th and 6th Divisions suffered severely in their long march, and were destined to suffer more before the day closed, the 6th especially, the "Marching Division," as their comrades of the war designated them. Spanish Slaughter The Spaniards having occupying the Pugade, the Portuguese guns were dragged up the hill and opened fire against the Calvinet, keeping up a thunderous cannonade against the enemy across the valley. About an hour before noon, while Beresford was still splashing on through the mud and mire, an unfortunate mishap befell Don Manuel Freire, flushed with his first success, he descended into the gorge below. Formed in two lines with a reserve in his rear he advanced to attack the breastwork on the Calvinet platform. Advancing boldly at first, the Spanish Infantry soon came under a withering fire of artillery and musketry, a battery on the canal also raked their right flank; and, turning to an officer beside him, Wellington is reported to have said, "Did you ever see nine hundred men run away?" The officer addressed admitted that he had not, and Wellington said, "Wait a minute, you will see it now." As he spoke, the right wing wavered, and the leading ranks flung themselves into a hollow road, twenty-five feet deep, desperately seeking shelter from the enemy fire. Leon de Sicilia's Cantabrians alone stood their ground somewhat sheltered by a bank; but the left wing and the second line turned and fled helter-skelter, a terror-stricken mass. The French rushing forward with triumphant yells and firing down into the hollow road, which was soon a hideous lane of dead and dying. The Spanish officers, with great courage, rallied their men and led them back again, but the sight that met their gaze as they reached the edge of the hollow put the finishing touch to their valour, and breaking rank they fled for the open country, hotly pursued by the enemy. This pursuit was ended by the intervention of the reserve artillery and Manners' Heavy Dragoons. The Light Division moved to its left to fill the gap left by the fleeing Spanish. More than fifteen hundred Spaniards were killed but Wellington, as he sat on his charger Copenhagen, afterwards to carry him at Waterloo, had more serious news brought to him. Picton’s Failure General Picton, whose eagerness for combat was so well known that his orders had been given to him both verbally and in writing, had disobeyed them, and turning his feint attack into a real one, had been defeated for the moment. Successful at first, the Fighting 3rd Division had driven the French outposts back about three miles on to the Jumeaux bridge. Picton, not content with this, sent six companies of the 74th Highland Regiment -- a corps which had lost the "garb of old Gaul" (kilt) five years before, and had twice as many Irish as Scots in its ranks - against the palisade at the bridgehead across an open stretch of plain. Brevet-Major Miller and Captain McQueen bravely led them forward; but the palisade was too high, and they had no ladders. Although they made the attempt, they were heavily repulsed, losing nearly four hundred officers and men, among them Colonel Forbes, killed, and General Brisbane was wounded. It was a severe repulse, and, taken together with the Spanish failure, might have proved serious, for Wellington now had no reserves. Hill was checked by the second line of entrenchments at St. Cyprien, and the French marshal was able by these reverses to withdraw about 15,000 men to reinforce the rest on the platforms, where Beresford now had victory or defeat in his own keeping. On the other side of the Ers the allied cavalry made two bold dashes - one against the bridge of Bordes, which sent Berton head over heels the left bank with barely time to destroy the road-way before the troopers were upon him. Soult's Last Stand Toulouse 1814

Well done, the Eighteenth... The Heroic KGL and Rockets Order of Battle: Soult Order of Battle: Wellington Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #66 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2002 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |