Klundert and Willemstad 1793

Dutch During the

Revolutionary Wars Part 10

Siege of Willenstad: March 14-16 and Aftermath

by Geert van Uythoven, Netherlands

| |

Thursday, 14 MarchThe French batteries were quiet this day, but their light infantry continued sniping at the defenders. Therefore, the besieged hoped that the French would end their siege because of the events in the eastern part of the Dutch Republic, already mentioned. Illustration 10.4; Silhouettes of a number of Dutch officers serving during the siege of Willemstad. After an engraving taken from Oldenborgh’s “De Belegering en Verdediging van de Willemstad. Top left: Col. Spiering. Top Right: Maj. van Nievelt. Center left: Kapt. Elsevier. Center right: Kapt. Schiphorst. Bottom left: Kapt. von Homperch. Bottom right: Kapt. de Pasque.” On this day, Ensign Rost returned from his reconnaissance, bringing message that the frigate ‘Venus’, armed with ten 12-pdr guns, was on its way from Hellevoetsluis to aid the fortress. He further reported that the French had dug themselves in along the Westdijk, and that their trenches and batteries reached as far as the first bend of the dike, very near to the city. From there, they were be able to cover the harbour, and to shoot a breach in the fortress wall. Therefore Governor van Boetzelaer was convinced that a sally was necessary to destroy the siege works of the French. A volunteer of the Regiment No. 8 Bosc de la Calmette crossed the ditch and reconnoitred the exact positions of the French, confirming everything Ensign Rost had reported. He had seen no French infantry. Although nearly the complete garrison volunteered to take part in the sally, it was decided that three men of each company would take part, to be led by a proper amount of NCO’s and officers. The sallying force therefore consisted of 45 men, two sergeants and two corporals, as well as six artillerymen who had volunteered. These would be led by the Ensigns Frederik Pieter Colthof (Regiment No. 8 Bosc de la Calmette) and Rost, and the Sous-Lieutenant J.J. Muller of the artillery. These three officers were the first to volunteer for the mission. To do as much damage as possible, except for their arms the party carried handspikes, hammers, nails, etc. Time of attack was fixed at dawn the next day. In the afternoon the frigate ‘Venus’ arrived, commanded by Lieutenant Kervel, opening fire at the French positions along the Westdijk immediately. Vice-Admiral Van Kinsbergen ordered Van Kervel to do everything possible to aid the garrison of Willemstad. The fire of the frigate was however not very effective. Friday, 15 MarchAt dawn the sallying force went on board of a ship and sailed outside the barricaded Waterpoort. There the party disembarked and marched as quiet as possible along the ‘Lantaarndijk’ in the direction of the Westdijk. When they arrived in the vicinity going on all fours, it became clear that about forty Frenchmen were present in the enemy trenches. The party halted and was divided in two groups, with the design to surprise the French and to cut off their retreat. The surprise was complete. The French were charged and cut down by musketry, the sabres or with handspikes. In a few seconds, between twenty and thirty Frenchmen were killed. Another nine of them were taken prisoner. The most severe loss for the French was however the death of two French engineers, Captain Dubois-Crancé and Captain Marescot, brother of the future general Armand-Samuel Marescot. The three cannon present were nailed, after which the party returned to the fortress, taking with them their prisoners. From the participants of this sally, not one was killed or wounded. Shortly after the return of their party, the Dutch heard drums beating everywhere around the fortress. Because of this, many of the besieged where convinced that the French were making themselves finally ready to retreat. However, the French would say good-bye in their own way. In the afternoon, the bombardment of the city was resumed, the French throwing bombs of 110 and 120 pound in the city, which caused much damage to the buildings. The bombardment lasted until nine in the evening, but no one was hurt. Saturday, 16 MarchBerneron finally had no choice then to retreat, in order not to be cut off from his own troops by the advance of the Dutch and Prussian forces.

[10]

The French used the cover of the night to prepare their retreat. At dawn they fired their last shots at the fortress to mask their departure, aided by a thick fog. To cover their retreat, at the hamlet Oudemolen they left behind an infantry battalion. At ten o’clock a French deserter arrived in front of the Landpoort. He declared to have served in the fortress Klundert as a gunner, and after being made prisoner by the French to be pressed in their service. Looking for the right time, he made good his escape when the French retreat began. That the siege of Willemstad really had ended was confirmed by a number of country people, also arriving at the fortress. After this news, Governor Von Boetzelaer ordered a detachment of sixty men with NCO’s, two subaltern officers and a captain, led by Sous-Major Lang, to

reconnoitre and to bring back to the fortress as much as possible ammunition left behind by the French. Soon they returned, bringing with them several guns, two mortars, a number of wagons loaded with bombs and cannon-balls, and a number of other things. They also brought with them three more deserters, of which two were chasseurs a cheval, complete with their horses! However, the danger was not gone completely. In the evening musket shots were heard in the vicinity of the fortress, fired by French light infantry stragglers which had stayed behind to rob the country-people. Therefore, many of these chose to stay in the fortress during the night.

The next day, a Sunday, divine service was held by the army-chaplain Lux of the Regiment Saxen-Gotha, to thank God for saving Willemstad. On the same day, a

number of British officers, including the Duke of York and General Lake, visited the fortress, to inspect the defence of the fortress and the siege works of the French. In addition, more guns, ammunition, and tools, left behind by the French, were brought into the fortress. In total the French left behind two metal mortars of 50 pound stone, two 18-pdr and four 12-pdr iron guns, eight wagons and an enormous amount of cannon-ball, grenades, and bombs.

During the siege, lasting sixteen days, the enormous amount of between 9-10,000 mostly red-hot cannonballs, and about 500 bombs, howitzer shells and grenades were shot at and inside the fortress. Almost unbelievable, losses in the besieged city were only fifteen death, of which four were civilians, and thirteen wounded! However, the damage done to the houses in the city and the properties of the country-people was enormous. In addition, huge parts of the surrounding polders had been inundated, and the dikes damaged. And although much financial help was given to the inhabitants that had suffered so much, many of them had become poor in a matter of weeks. Although a small faith of arms, the successful defence of Willemstad grew out to the national symbol of resistance to the French aggressor, were a mere five hundred defenders resisted eight thousand besiegers.

As such, it became a great boost of morale for the Dutch still willing to resist the French, out of proportion with the real strategic value of the fortress. The only

strategic value was that, having taken Willemstad, the French would have been able to prevent all Dutch Shipping on the Hollandsch Diep. Although this would

hamper Dutch communications, it would in no way prevent it, because the Dutch ships could easily make detours by other waterways. However, needing a national

symbol of resistance to the French, a fortress so close to the heart of the Dutch republic, resisting the French successfully, was a chance the Dutch government quickly used. Therefore, the defenders were overwhelmed with rewards. The Governor, Baron van Boetzelaer, was promoted to Lieutenant-General, and received a golden honorary sword for his efforts, still present in the government house today.

With this ends the story of the siege of Willemstad. In the next part, I will treat the defence of the Dutch Republic, and the arrival of the first British troops, following with the events in the east: the advance of the Prussian and Austrian armies.

By accident, in my article about the capture of Breda and Geertruidenberg that has appeared in First Empire No. 60, some lines were left out, following page 16, 1st column, 3rd line:

" ...Lieutenant-General Johan Hendrik Bedaulx. The defences of Geertruidenberg proper consisted only of a brick stonewall surrounding the city. The city itself was surrounded by a number of outlying strongholds. In the north, near the river Meuse, this was the only defence. On the other sides the defences were better because of the inundation of the surrounding fields and the river Donge, flowing around the city in the south and the east. It was estimated that the fortress could withstand a regular siege for at least three weeks. The garrison consisted of eight- or nine-hundred infantry from the Swiss regiment in Dutch service ‘Hirzel’, and part of the Guard Dragoon Regiment.

However, most of the inundations... In addition, in the article about Klundert and Willemstad that has appeared in First Empire No. 62, the wrong illustration 9.3 was depicted. The right illustration follows below:

Aa, Cornelis van der Geschiedenis van den jongst-geëindigden oorlog, tot op het sluiten van den vrede te Amiëns, bijzonder met betrekking tot de Bataafsche Republiek Dl 1 (Amsterdam 1802)

[1] According to Van Nispen, the explosion was not caused by the bombardment, but by carelessness with the gunpowder by the gunners. Van Oldenborgh gives no cause.

Siege of Willemstad 1793 Dutch in Revolutionary Wars Part 10

The Dutch During the Revolutionary Wars

|

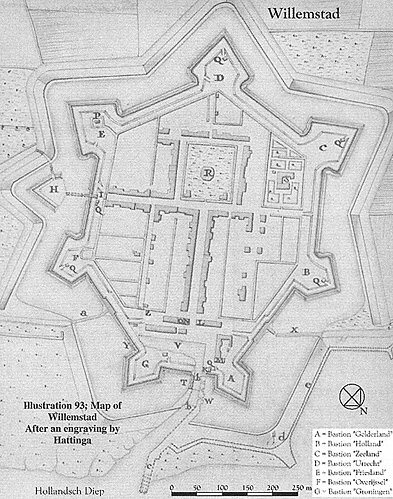

Illustration 9.3; Map of Willemstad After an engraving by Hattinga

Illustration 9.3; Map of Willemstad After an engraving by Hattinga