The Battle Of

The Gohrde 1813

Background and Battle

by John Walsh

| |

General Pecheux watched the troops march past and tried to offer a smile as they tramped along the narrow road, surrounded on both sides by a deep, dark density of trees. They seemed cheerful enough, even though quite a few of them had yet to see their seventeenth birthday, the Marie-Louises of the French army. Their emperor had given them victories at Lutzen and Bautzen and perhaps those events cheered them on.

The disaster on the Katzbach, a month earlier, when Blucher savagely mauled MacDonald, was also pushed to one side by Napoleon's great victory at Dresden. To Pecheux it was a warning, to others, it was just MacDonald's fault for stupidly disobeying orders. He noticed some of the Marie-Louises were barefoot and many marched out of step but this wasn't the time for chastisement. He nervously fingered his timepiece, still damp with the early morning dew and flipped open the lid. It was nearly nine o'clock. He fumbled slightly as he placed it back in his pocket. He had every reason to be nervous. The enemy were in retreat but not decisively defeated. Napoleon was confident they soon would be. Then again, he was equally confident about Russia. Pecheux sighed. At least he wasn't fighting in the Tsar's kingdom. The Russian campaign was barely a year old but had already fallen into folklore with survivors of the Grand Armee. When he thought of Russia, Pecheux was glad he was in Germany, even though it was September and winter wouldn't be too far away. He prayed Napoleon would lead them to a glorious victory and hopefully, a speedy end to the campaign. He longed to return to the warmth and comfort of France.

A Simple Task A simple task if he had been leading the men of the old Grand Armee. However, of the troops comprising his small command, very few were veterans of Austerlitz, Jena, Borodino and other great campaigns. Most of those he now led were raw recruits, trained on the march. Young men who had only recently learned what it was like to fire a musket in battle, what it was like to see a close friend die beside them. Some of the young warriors looked as though they were still in shock. He commanded six battalions or rather, six half battalions. They totalled less than four thousand men, including the artillery, of which he had very little: two howitzers and six 6 pounders. The situation with the cavalry was worse, as it was with the whole of the French Army, Barely a hundred troopers from the 28th Chasseurs a Cheval regiment. Not enough to attack with and certainly not enough to pursue. But hopefully, enough to tackle the small portion of enemy troops said to be operating as guerillas. The area they were marching through was ideal for ambushes. Lots of thick woods and forests with ravines and undulating land masses in-between. He was just glad there were no reports of large enemy formations in the vicinity. Whole armies could be hidden from view until too late. They were marching along the road to Dannenburg, which ran parallel to the River Elbe when, just after nine, Pecheux's advance guard came into contact with a large force of cossacks. After a brief skirmish the cossacks withdrew and the French followed, which was exactly what the wild, allied horsemen wanted them to do. However, call it a soldier's instinct, but Pecheux became instantly suspicious when more allied troops were spotted and ordered an orderly retreat back through the woods. He was just in time. More cossacks appeared on the left, followed by infantry. Large numbers of enemy troops were seen moving on his right and even more swarming among the trees to his front. The large undetected enemy formation he so feared was a reality and in full mass attack. The French had almost blundered into a carefully laid trap and were now being forced back. In this terrain it would have to be a slow fighting retreat and by the enemy's movements, Pecheux soon realised he was vastly outnumbered and had no chance of outrunning them. The troops the French had just encountered belonged to the Swedish born Count Graf Wallmoden, a general in the Russian army. One of his staff officers was said to be the famous Prussian, Carl von Clausewitz. Wallmoden's command contained a multinational force of Russians, Prussians, Hanoverians, Mecklenburgers and even a regiment of British troops. It consisted of around seventeen battalions of infantry, five cavalry and three cossack regiments, three horse batteries, two foot batteries, numbering between thirty to forty guns and half a rocket battery. A total of over twelve thousand men. This was after Wallmoden had left behind his Swedish contingent. Pecheux was outnumbered by at least three to one. On paper, it looked allover for the French. However, Pecheux had other ideas. He knew he had to make a stand and he knew where. He retreated to a position not far from the Gohrde woods.

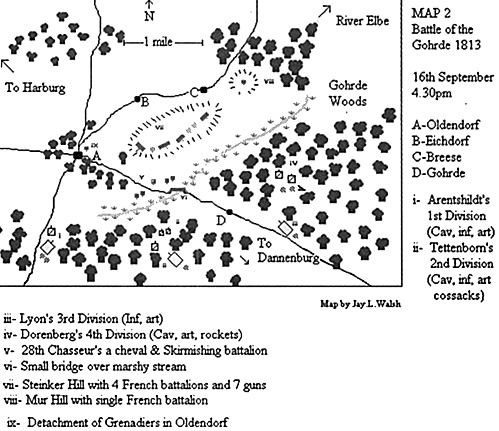

The Chasseurs were formed forward on the French right, with the role of stopping any Cossacks from advancing out of the woods. They were supported by one of the battalions of the 3rd Regiment de Line, in skirmishing formation. This battalion had, for some time, been holding off the allied troops advancing through the woods. But now, under pressure, they had to fall back. The remaining battalion was positioned as a reserve on Mur Hill, near Breese. The position of the eighth gun is unknown and may well have been captured early on. Wallmoden's force consisted of four divisions in two columns. The left column contained the 1st Division, commanded by Colonel Frederich von Arentschildt. The main column contained the advance guard, the 2nd Division, commanded by Generalmajor von Tettenborn, which had been busy fighting the French battalion holding the woods. Following this and led by Wallmoden himself, was Major General Lyon's 3rd Division and Generalmajor von Dorenberg's 4th Cavalry Division. (A single battalion of the British 73rd Highland regiment was part of Lyon's division.) Wallmoden's plan was to envelope Pecheux's position on three sides, simultaneously. Arentschildt was to attack the French far right, Tettenborn the French right of centre, Lyon the centre and Dorenberg , the French left flank. If they attacked as planned they should have swamped the French position fairly easily. However, what works in the mind and on paper, doesn't always work in the field. His troops, rather than strike the French positions together, attacked piecemeal, as and when they emerged from the Gohrde woods. More Gohrde

Battle of Gohrde: Main Action Battle of Gohrde: Wargaming Battle of Gohrde: Order of Battle Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #51 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 2000 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |

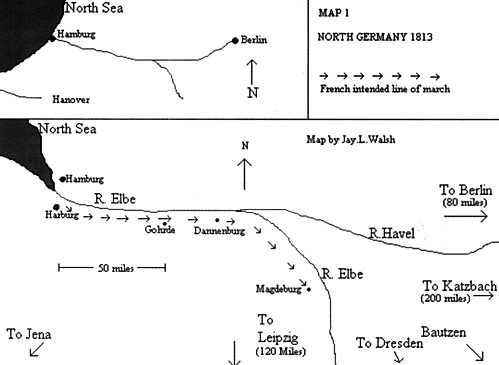

Unfortunately, home would have to wait. He had work to do. His orders were to advance east from Harburg to Dannenburg and then south to Magdeburg (Map 1) and to clear the left bank of the River Elbe of enemy troops, who were engaged in guerilla activity. A simple enough task for someone so ably experienced.

Unfortunately, home would have to wait. He had work to do. His orders were to advance east from Harburg to Dannenburg and then south to Magdeburg (Map 1) and to clear the left bank of the River Elbe of enemy troops, who were engaged in guerilla activity. A simple enough task for someone so ably experienced.

Pecheux stationed his troops on a rise of ground, known as Steinker Hill, in the middle of a small plain, not far from the edge of the massive Gohrde woods. (Map 2) The rise gave the French a good line of sight and fire, except for the small wood which formed their right flank. Between Steinker Hill and the Gohrde woods was a marshy stream, making movement difficult for anyone trying to approach the hill. About five hundred yards in the plain behind the rise were three villages. Oldendorf, Eichdorf and Breese. Behind the village of Oldendorf was the way back to Harburg and the path the French must take if they were forced to retreat. Some grenadiers were placed in the village to cover the escape route. Pecheux positioned four of his battalions on the rise, with two cannons on the right and five on the left.

Pecheux stationed his troops on a rise of ground, known as Steinker Hill, in the middle of a small plain, not far from the edge of the massive Gohrde woods. (Map 2) The rise gave the French a good line of sight and fire, except for the small wood which formed their right flank. Between Steinker Hill and the Gohrde woods was a marshy stream, making movement difficult for anyone trying to approach the hill. About five hundred yards in the plain behind the rise were three villages. Oldendorf, Eichdorf and Breese. Behind the village of Oldendorf was the way back to Harburg and the path the French must take if they were forced to retreat. Some grenadiers were placed in the village to cover the escape route. Pecheux positioned four of his battalions on the rise, with two cannons on the right and five on the left.