The Battle Of Montereau

18th February 1814

The Battle

by Major A. W. Field

| |

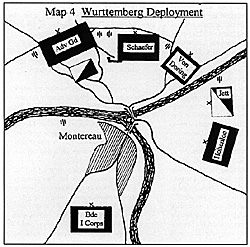

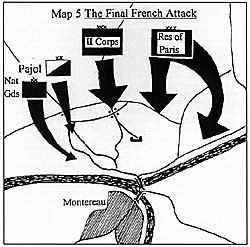

French sources disagree on which formations were first to arrive in front of the Wurttemberg positions; however, all the eyewitness accounts agree that it was General Chataux (commanding a division of Victor's corps) who approached along the road from Nangis at about 9.00am. No doubt by this time he was aware of the need to seize the bridges as quickly as possible and consequently launched an immediate attack from the village of Forges on the Wurttemberg positions around Villaron. Outnumbered in manpower, but more crucially in artillery, it is no surprise that this attack failed. Victor's other division (Duhesme) arrived shortly afterwards and renewed the attack on Villaron. However, this attack failed in its turn in the face of heavy artillery fire and the Wurttemberg cavalry launched an effective counter-attack which tumbled the French forces back to the safety of the woodline to their rear. It was now clear to Victor that alone, he had insufficient combat power to defeat the Wurttembergers in their strong position. His uncoordinated attacks with insufficient artillery preparation, launched piecemeal as more troops came up, were doomed to failure. General Chataux, Victor's son-in law, was mortally wounded whilst leading one of the initial assaults. Victor now awaited the arrival of Gerard with his Reserve of Paris before he felt he could launch a new attack. However, Gerard's arrival at about 11.00am coincided with Victor's dismissal as commander of the II Corps by Napoleon, and his succession by Gerard. The whole of Gerard's troops were not up until 12.30. Even now the French had not accumulated an overwhelming superiority in numbers and Gerard realised that his primary concern was to concentrate all his forces and to neutralise the strong Wurttemberg artillery which was dominating the battle. He therefore had all the available artillery brought forward which gave him around 40 guns. A fierce artillery duel now started as the French prepared the decisive attack. Napoleon had spent the night of the 17th in Nangis. Aware that Montereau had not been taken the night before he led his headquarters staff rapidly towards that town. By 9.00am he arrived in the square of Villeneuvre-les-Bordes where he received the first reports on the fighting which he was able to hear in the distance. Still furious by Victor's failure he was impatient to push the attack on and his ADC General Dejean was despatched to hurry things along. It was from him that Victor received news of his dismissal. Soon afterwards Napoleon left for the battlefield. Having gone some way to silencing the Wurttemberg artillery and softening up the infantry, Gerard was now in a position to launch another attack to seize the plateau. He had been further reinforced by the arrival of General Pajol with his National Guards (3000), cavalry (1300) and Gendarmes (800). Pajol was ordered to attack the Wurttemberg left flank whilst Gerard led the main attack against Villaron. This assault lasted around an hour but still no impression could be made on the main position. By this time Gerard commanded around 12,000 men, but despite this superiority the ground favoured the defence and the attacks do not seem to have been pushed home with much conviction. Napoleon arrived on the battlefield with the infantry and artillery of the Guard sometime between 2 and 3.00pm. As was so often the case, particularly in this campaign, his appearance had an immediate impact. He ordered Gerard to mount a new, coordinated assault. This was to be launched in four columns (see Map 5): the National Guards were to turn the Wurttemberg left flank whilst Duhesme's and Chataux's divisions, reinforced by Pajol's Gendarmes, were to seize Villaron. The Reserve of Paris were to assault the Surville Chateau and to attack around the right flank along the bank of the Seine. The Old Guard infantry were held in reserve but the artillery, bringing the overall French total to 70 guns, was rushed forward to support the attack. As the preparations for this attack were being made and in the face of increasing artillery fire the Crown Prince of Wurttemberg realised his position was becoming untenable. His original plan to hold until nightfall was clearly not going to be possible and he consequently despatched a message to Schwarzenberg explaining that he was being forced to withdraw. His plan was for Schaefer's Austrian brigade to hold the Surville Chateau to cover the withdrawal. However, it was now that the weakness of the Wurttemberg position began to show itself: although the Wurttemberg troops had fought well up until now, as the need for withdrawal became more obvious, so the soldier's attention was concentrated less on the growing French pressure and more on the need for self-preservation. This manifested itself in the need to get across the bridges before the French pressed the attack home. As the attack developed the Wurttembergers found their flanks under considerable pressure. When the orders for withdrawal were given, what started as an orderly withdrawal by echelon soon became a free for all as the Wurttemberg troops broke and ran for the bridges.brigade to hold the Surville Chateau to cover the withdrawal. However, it was now that the weakness of the Wurttemberg position began to show itself: although the Wurttemberg troops had fought well up until now, as the need for withdrawal became more obvious, so the soldier's attention was concentrated less on the growing French pressure and more on the need for self-preservation. This manifested itself in the need to get across the bridges before the French pressed the attack home.

As the attack developed the Wurttembergers found their flanks under considerable pressure. When the orders for withdrawal were given, what started as an orderly withdrawal by echelon soon became a free for all as the Wurttemberg troops broke and ran for the bridges. Pajol seized the opportunity to charge the fugitives and Napoleon launched the four Service Squadrons led by Dautencourt, and even his own headquarters staff led by Marshal Lefebvre, in support. Pajol sent Guyot's brigade off first then led the other two himself, even though his arm was in a sling. The charge seems to have followed the road which runs round the west of the plateau and down into the town. Charging in an almost uncontrollable torrent these inexperienced cavalry crashed into the fleeing Wurttembergers, their momentum carrying them across the bridges before they could be destroyed. The fact that there was no Wurttemberg cavalry to contest this charge suggests that they had already withdrawn. The Crown Prince of Wurttemberg himself was involved in the fighting round the bridges. Captain Coignet, who took part in the charge with Napoleon's staff writes this in his famous Notebooks;

The two bridges had been prepared for destruction and were protected by the battalion from Hohenloe's brigade. However, a combination of the French artillery fire, the presence of their own retreating comrades and the sudden charge of the French cavalry resulted in an incomplete job and the guard force being dispersed. Napoleon had got his bridges. In the meantime the Surville Chateau was stormed and most of the Austrian brigade there, including the commander and all the regimental headquarters of the Collerado Regiment, were captured. With the Surville heights secure the Guard artillery was brought forward and proceeded to pour a plunging fire into the disorganised Wurttemberg infantry which formed a dense mass trying to escape across the bridges. The chaos around the bridges was exacerbated by the Crown Prince ordering Hohenloe to counter attack and rescue those cut off north of the river. This attack soon crumbled in the face of heavy artillery fire from the Guard batteries which now overlooked the bridges and the crowd of disordered soldiers mixed with victorious French cavalry coming in the opposite direction. The Austrian batteries on the southern bank of the Seine endeavoured to cover the retreat; Fain describes the Austrian balls which "hissed like the wind over the heights of Surville." But the French now had 70 guns deployed and Napoleon himself aimed some of them. The gunners were concerned that he would be hit and urged him to move to a safer vantage point; but he was clearly enjoying himself and replied to their protests "come my brave fellows, fear not, the ball which is to kill me has not yet been cast". Most of the Wurttembergers who did not get across the bridges joined the Austrians as prisoners. Those who did get across were still not safe: the inhabitants of Montereau had been harshly treated and were quite prepared to vent their anger on the fleeing allied troops: "They ran to join our attack columns, offered themselves as guides; others with anything that came to hand, the muskets of the vanquished, the tiles of their houses, their heaviest furniture, formed their weapons. Most, mounted on their roofs ambushed the rear of their former tormentors, rained down every sort of death on the desperate crowd of their former oppressors". It was only when they were clear of the town that their reserves were able to support them. Coignet continues his account: "When we came to a fine road which led to St Dizier, in front of an immense plain, the marshal ordered us to follow up our charge; but the Emperor seeing us in certain peril, ordered a battalion of Chasseurs to put down their knapsacks, and go to our assistance. This battalion saved us. We were driven back by a body of cavalry." The wreck of the Crown Prince's corps, or those who were able to get across the bridges, were now able to take refuge behind the Wurttemberg cavalry, the brigade of Hohenloe or the Austrians left behind by Bianchi. From Coignet's account it seems as if Jett's Wurttemberg cavalry played a significant part in slowing down any pursuit as it left the suburbs of the town and in covering the eventual withdrawal towards La Tombe. Bianchi's brigade, on the left bank of the Yonne were unable to get across to join this force and were pushed back to the southeast until they were able to meet up with the rearguard of their own corps at Serotin. The battle was now effectively over. All that remained was for the French to round up the considerable number of Wurttemberg and Austrian troops who were trapped on the north bank of the Seine or in the town. As with most battles it is almost impossible to give accurate figures for casualties. French sources give Wurttemberg losses as between 5 and 6,000 men, 3,400 of which were prisoners, four colours and between 6 and 15 guns. German accounts reduce allied losses to 4,000, although given that the Crown Prince only deployed 10,000 north of the river this is still a considerable proportion of those who did the majority of the fighting. Only de Segur's account gives French casualties; his figure of 4,000 seems high but perhaps is a reflection of the poorly coordinated early French attacks and the tenacious resistance put up by the Wurttembergers. Napoleon's Ninth Bulletin of the 20th Feb said: "Our loss in the battles of Nangis and Montereau does not exceed 400 men killed and wounded; which, although exceedingly improbable, is nevertheless the truth". Perhaps the saying "to lie like a bulletin" has never been more apt! General Chataux was later to die of his wounds and both Delort and Pajol were also wounded. Napoleon apparently ordered the Wurttemberg shakos to be thrown into the Seine so that they would be seen by the inhabitants of Paris. AftermathNapoleon's offensive which started on the 17th had forced Schwarzenberg's Army of Bohemia, which was twice the size of the forces the Emperor had available, into a rather precipitous retreat which did not end until Troyes. Napoleon wrote: "My heart is relieved, I have saved the capital of my Empire". However, the need to save Paris had forced him to abandon an attack on the Bohemian Army's flank as he had originally planned and his attack on Montereau had failed to cut off Bianchi's Corps. All he had actually achieved was to inflict a considerable defeat on a single corps and pushed Schwarzenberg back on his own communications; it was merely a temporary respite as events were later to prove. However, it was an important victory for morale reasons, as Baron Fain wrote: "Our success at once supported the ardour of our troops, roused the enthusiasm of the country, and excited to the utmost degree the devotedness of our young officers...". Unfortunately it did not have the same effect on the marshals. ConclusionI cannot help wondering what would have happened if, after having fought a sharp action against the Bavarian V Corps already on the 17th, Victor had pushed his tired troops on to Montereau. Wurttemberg was already occupying that place and even if he was not deployed to defend it he still outnumbered Victor's corps by three to one! The following day, despite the courageous early assaults by Chataux and Duhesme, the French did not achieve any superiority in men and guns until the whole of II Corps, the Reserve of Paris and Pajol's troops had come up, and even then there was little to choose between the two sides. Once again it was Napoleon's presence rather than overwhelming numbers which seems to have tipped the balance.even if he was not deployed to defend it he still outnumbered Victor's corps by three to one! The following day, despite the courageous early assaults by Chataux and Duhesme, the French did not achieve any superiority in men and guns until the whole of II Corps, the Reserve of Paris and Pajol's troops had come up, and even then there was little to choose between the two sides. Once again it was Napoleon's presence rather than overwhelming numbers which seems to have tipped the balance. Napoleon's belief that Victor could have seized the bridges in some sort of coup de main was probably wishful thinking. Equally, I have no reliable evidence to confirm whether Wurttemberg was ordered by Schwarzenberg to keep both bridges open until the night of the 18th, thus forcing him to defend a position with a major obstacle to his back. If he did it was certainly a "hospital pass" and the IV Corps paid a very heavy price. Either way, for the second time in ten days Napoleon's energy and drive had thrown back allied advances on Paris. Unfortunately the resources and stamina of the allies were to prove too much even for his genius and the campaign finally ended in the fall of Paris and the Emperor's first abdication. Thanks My thanks to John Henderson of the NA's German States Research Group for providing me with a German account of the battle which enabled me to verify French accounts and, I hope, to give a more balanced narrative. SourcesCoignet, The Notebooks of Captain Coignet. More Montereau

Battle of Montereau: Opposing Forces, Ground, Deployments Battle of Montereau: The Battle Battle of Montereau: Order of Battle Revised With New Information (FE51) Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #45 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 1999 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |