The Battle Of Montereau

The Battle Of Montereau

18th February 1814

Background, Early Campaign, Prelude

by Major A. W. Field

| |

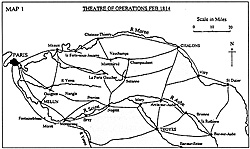

BackgroundAfter its catastrophic defeat at Leipzig in October 1813 the demoralised and greatly diminished Grande Armee struggled back into France. Deserted by most of her former allies, who now took up arms against her, France faced invasion from Spain, the Netherlands and Germany. The most immediate threat came from the armies of Blucher (the Army of Silesia), consisting of Russian and Prussian troops, and Schwarzenberg (the Army of Bohemia, although now more correctly known as the Grand Army) consisting of Austrian, Russian, Bavarian and Wurttemberg corps, who crossed the Rhine into France early in the year of 1814. With a combined strength in the order of 250,000 men, the French Marshals were in no position to offer serious opposition. It was only the presence of Napoleon at the front that was likely to galvanise the French army into a truly cohesive fighting force. Having made superhuman efforts to raise new troops and sort out the deteriorating political situation in Paris the Emperor moved to Chalons to join up with his forces on the 25th January. The Early CampaignNapoleon considered Blucher to be the most dangerous of his opponents. Despite the Silesian Army being considerably smaller than the Army of Bohemia, Blucher's well known aggressive spirit and ability to motivate his troops made it likely that he was the allied commander most likely to threaten Paris first. If Napoleon was able to inflict a convincing defeat on Blucher then it was quite possible that the more timid Schwarzenberg may abandon, or at least reconsider, his own tentative advance on the capital.

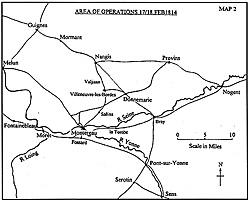

Napoleon's early manoeuvrings to achieve this were a failure: Blucher's army slipped away at St Dizier and the first engagement at Brienne (29th Jan) was inconclusive. Indeed this battle merely pushed Blucher into the Bohemian Army's outposts and thus concentrated they were able to inflict a sharp defeat on Napoleon at La Rothiere on the 31st Jan. Although the French fought well in this battle, indeed the Marie Louises performed far better than could have been expected, they were heavily outnumbered and forced to retreat having lost at least 50 guns and around 6000 casualties. To make matters worse between 4 and 6000 men deserted the French army over the following few days. With Paris thrown into a panic and his army in disarray it seems that the allies thought Napoleon was finished. Leaving him virtually uncovered, the two armies parted once more: Blucher was to advance on the unprotected capital along the line of the Marne where only a weak force (8000) under Macdonald was able to confront him, whilst the Bohemian Army would advance along the line of the Aube and Seine. Blucher set off with his usual impetuosity and as expected Macdonald could do little with his meagre force to slow him down, let alone stop him. However, as the advance gathered pace so the various corps spread out until they lost the mutual support so vital in this sort of operation. Made aware of the developing situation by Marmont whom he had sent north towards Sezanne, Napoleon immediately recognised the opportunity to strike with superior numbers against each of the separated corps. Between the 10th and 14th Feb Napoleon inflicted a series of stinging defeats at Champaubert, Montmirail, Chateau-Thierry and Vauchamps on each of Blucher's corps in what is considered as one of his most brilliant campaigns. For the loss of little over 3,000 men he had inflicted around 15,000 on the Army of Silesia. No doubt Napoleon cursed the need to now turn his attention away from Blucher's disordered retreat and towards the Army of Bohemia. Whilst Napoleon had been thrashing Blucher, Schwarzenberg had slowly and methodically advanced towards Paris. Once again the forces the Emperor had left with Victor and Oudinot to oppose them had proved incapable of doing little more than withdraw before the advancing allied columns. The leading allied troops had reached as far as Fontainebleau and it was vital that Napoleon move south to relieve the growing pressure as soon as possible. Leaving Marmont and Mortier with the VI Corps and part of the Guard to keep an eye on Blucher, on the 15th Feb Napoleon left Montmirail with the balance of his forces. Travelling via Meaux he arrived at Guignes on the 16th; using forced marches and requisitioned carts and wagons his troops covered 47 miles in just 36 hours. Prelude To BattleIn Guignes Napoleon was briefed on the situation; it was not good (see Map 2). The deployment of the Bohemian Army was:

- Wrede (V (Austro-Bavarian) Corps) was at Donnemarie. - Wurttemberg (IV (Wurttemberg) Corps) was at Montereau. - Bianchi (I (Austrian) Corps) was at Moret and as far forward as Fontainebleau. - Gyulai ( III (Austrian) Corps) was at Pont-sur-Yonne. - Barclay (Russo-Prussian Guards) was around Nogent. Oudinot and Victor, who had recently been joined by Macdonald, had concentrated their forces behind the line of the River Yeres. Although Napoleon was now in a position to guard his capital, as far as the campaign was concerned this in itself was not enough; it was vital that he score some sort of significant victory over the Bohemian Army as he had done against Blucher in order to rally Paris to his support. The overextended and isolated I Austrian Corps at Moret and Fontainebleau gave him an opportunity to do this, providing he could seize a crossing over the Seine in order to cut it off from the rest of the army. It was vital that his counter offensive was swift and carried out with vigour. Napoleon Strikes

On the 17th Napoleon struck. Wittgenstein's advance guard at Mormont was surprised by Gerard and badly beaten. At Nangis, Wrede's advance guard was also pushed back with loss and retired towards its main body. As his own main body reached Nangis Napoleon split his pursuit:

- Oudinot (VII Corps) and Kellerman's cavalry were to follow Wittgenstein towards Provins. - Macdonald (XI Corps) and two cavalry divisions were to advance on Bray. - The Guard would form the reserve. Later in the day Victor again contacted and defeated the Bavarians at Valjuan but failed to follow up his victory with determination. However, as the 17th unfolded and the chances of seizing a crossing at Bray or Nogent receded, it became clear to Napoleon that the success of his plan relied on Victor capturing Montereau before it could be properly defended. At 3.30pm Berthier sent the following orders to Victor:

However, instead of pushing hard for the bridges as directed and taking advantage of the disarray in the allied ranks in the face of this unexpected attack, Victor chose to rest his troops short of the town, spend the night in the comfort of the Chateau of Montigny and send only a reconnaissance forward. This gave the Crown Prince of Wurttemberg the opportunity to properly coordinate his defence. Napoleon believed the bridge had been taken and it is no surprise to find he was furious when told the truth. Indeed, Napoleon was so angry that he was now unlikely to achieve the full effect of his planned offensive that he later replaced Victor as commander of II Corps. In concert with the moves of the main body, Pajol, with a weak division of cavalry and a division of National Guards (Pacthod), advanced down the Melun to Montereau road. Thus on the 18th Feb both Victor and Pajol would arrive at Montereau. To his credit Schwarzenberg appreciated the danger to I Corps and the strategic importance of the bridges at Montereau. The Prince of Wurttemberg had therefore been ordered by Schwarzenberg to hold the town in order for Bianchi to withdraw his corps. It seems that his orders required him to keep open the bridges until the night of the 18th. This was a somewhat curious order if it is indeed true; Bianchi's corps could quite well have crossed the Yonne at Pont-sur-Yonne, thus keeping some ground between himself and Napoleon, and even if he did have to use the bridge at Montereau I see no requirement to hold open the bridge over the Seine. By doing so the Prince of Wurttemberg was forced to defend the right bank of the Seine with the river directly behind him, a catastrophe waiting to happen as the Russians had found out at Friedland. In order to provide some support to the Prince of Wurttemberg, Bianchi reinforced the IV Corps with a brigade and two batteries from his own corps. More Montereau

Battle of Montereau: Opposing Forces, Ground, Deployments Battle of Montereau: The Battle Battle of Montereau: Order of Battle Revised With New Information (FE51) Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #45 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 1999 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |