The Battle Of Montereau

18th February 1814

Opposing Forces, Ground, Deployments

by Major A. W. Field

| |

The Opposing Forces

At right: National Guardsman (left) and Le Petit Gendarmerie (right)

Initially only Chataux's division of the II Corps was in a position to attack on the morning of the 18th; but as the day wore on he was joined by the rest of Victor's II Corps, Gerard's Reserve of Paris, Pajol's composite cavalry division, National Guard division and 800 Gendarmes recently arrived from Spain, and finally Napoleon with the Guard. By the end of the day the French had concentrated around 17,000 men (not the 30,000 claimed by many allied commentators) in front of the town (see the Orders of Battle). These forces represented an entire cross section of the many troop types that Napoleon was forced to call upon in his penultimate campaign. Pajol's small cavalry division reflected the difficulties of trying to raise such troops quickly; almost untrained and indifferently equipped most of his troopers needed both hands to control and stay on their mounts (Marshal de Saxe writing before the Napoleonic wars believed it took 10 years to fully "make" a cavalryman). Needless to say this made carrying out a charge, sword-in-hand, almost impossible; as one of the brigade commanders (Gen Delort) said; "only a madman would order me to charge with such troops". It is ironic that despite this, Pajol and his division were to make a significant contribution to the French victory! It is possible however, that a few of the detachments that made up this provisional division came from the excellent dragoon regiments that had recently arrived from Spain; Napoleon had recently declared a reorganisation of the cavalry and it is impossible to be sure if all of the detachments in Pajol's division had been despatched from the depots or if some had indeed come from the parent regiments. It is important to understand that during this campaign the French formations that were engaged were mere shadows of those that made up the armies of earlier in the wars. For example, a corps in 1805/6 could be between 20 and 30,000 men; at Montereau Victor's II Corps was under 4,000. Divisions that could once boast 6 to 10,000 men were now frequently under 2,000, containing battalions that had less than 100 men. Casualties, recruiting problems, sickness, hard marching and desertion all contributed to this problem. Pajol's National Guards, composed in the most part of men from Brest and Poitu, were also of very limited combat value. Again, hardly trained and dressed in "round hats and country blouses" they lacked the organisation and discipline to manoeuvre on the battlefield and press home an attack. This is not to say that they lacked courage or the will to fight as they were later to prove at Fere Champenoise, but were perhaps better suited to a "firing line" on the defensive. Before the battle they were reviewed by Napoleon who said to them "Show them what the men of the West are capable; they were at all times the faithful defenders of their country, and the firmest support of the monarchy". The Petit Gendarmarie d'Espagne on the other hand were clearly attached to Pajol to stiffen his other forces. The Gendarmes had been raised to protect the French lines of communication and conduct anti-partisan operations in Spain. They were tough, experienced soldiers and after seeing them perform at Montereau Napoleon attached them to his Guard. Victor's and Gerard's troops consisted mainly of Marie-Louises strengthened by a hardcore and cadre of veterans. Although lacking in training and equipment those who stuck with the Eagles fought valiantly, even if the options for their employment on the battlefield were restricted; Gerard's troops in particular had performed creditably at La Rothiere. From the strengths of the divisions given in the orders of battle it is clear how casualties, the rigours of campaign and desertions had dramatically thinned their ranks. In the presence of Napoleon and after a run of successes they performed well enough. However, when Napoleon was not present and in the face of superior allied numbers their morale was brittle. Then of course there was the Old Guard; although the infantry stood in reserve throughout their time on the battlefield there can be little doubt that their mere presence would have been enough to raise the sagging morale of the other troops. However, it is to the credit of the line infantry that these elite troops did not have to be called on to take any part in the battle. But if the infantry took no part in the fighting there can be little doubt that it was the contribution of the Guard artillery which was the turning point of the battle and the support of the Service Squadrons to Pajol's charge which turned the defeat of the Wurttembergers into a rout. Throughout the campaign Napoleon was increasingly forced to commit his Guard to ensure battlefield success. Wurttembergers The Wurttembergers had been original members of the Confederation of the Rhine and enthusiastic allies of the French. In Napoleon's early campaigns their contribution to his string of successes, the magnetism of the Emperor and their territorial gains had strengthened the alliance. However, over the years the treatment of the army as second class citizens, the lack of recognition of their contribution, the constant demand for more soldiers and the spread of German nationalism began to undermine their support. Although it was a combination of these factors that led to their change of allegiance in 1813 there can be little doubt that there was a clear recognition that Napoleon's star was on the wane. The maintenance of crown and territory relied on a large dose of a recognition of the inevitable. Once the Wurttemberg army had reorganised and trained along French lines and benefited from campaign experience it was considered as one of the more effective of France's allies. The soldiers proved to be tough and reliable. However, their participation in the Invasion of Russia effectively wiped the army out and like many others the units that took the field in 1813 were poorly trained and equipped. As growing discontent grew over the alliance with France so their battlefield performance and motivation suffered. Wurttemberg provided the 38th Division and a brigade of cavalry for the campaign in Germany. Of the original infantry strength of around 4000 at the start of the battle at Dennewitz over 50% became casualties or prisoners, and after fighting at Wartenberg only 1000 infantry and 125 cavalry returned to Wurttemberg once they declared for the allies in November 1813. The cavalry brigade deserted at Leipzig. The cost of changing sides was the need to raise another new force for the invasion of France. It is impossible to know the percentage of those who were taken prisoner or deserted during 1813 that returned to the colours to take up arms again. However, it is safe to say that a large number would have been newly raised conscripts or members of the Land Regiments called up for regular service, and hence lacked the experience of many of their new allies. Virtually the whole of the Wurttemberg regular army constituted the allied IV Corps; seven of the ten infantry regiments and four of the five cavalry regiments (see order of battle). No doubt to stiffen this new organisation and to warrant the title of "corps" an Austrian infantry brigade, cavalry regiment and two artillery batteries were attached. The Corps was organised into an advanced guard of a cavalry brigade and a light infantry brigade and a main body of a Wurttemberg infantry division (two brigades), a Wurttemberg cavalry brigade and an Austrian infantry brigade. The Corps was commanded by the Crown Prince of Wurttemberg and its total strength was about 14,000 at the start of the campaign and about 12,000 by the time of Montereau. The performance of the Corps up to the 18 Feb had been inauspicious but certainly not bad. Its main contribution had been at the battle at La Rothiere where it had advanced rather tentatively against Victor's corps (whom it would meet again at Montereau) and attacked the village of La Giberie. Having taken it and then lost it again to a counter-attack the Crown Prince rather panicked and demanded reinforcements and supporting attacks on his flanks. Although something of an overreaction this produced the desired effect and the attacks of the Bavarians on their right flank allowed the Wurttembergers to retake La Giberie and move on to take Petit Mesnil against obstinate French resistance. The cavalry performed rather better than the infantry and conducted some successful charges against the French cavalry until the action ended in the darkness.where it had advanced rather tentatively against Victor's corps (whom it would meet again at Montereau) and attacked the village of La Giberie. Having taken it and then lost it again to a counter-attack the Crown Prince rather panicked and demanded reinforcements and supporting attacks on his flanks. Although something of an overreaction this produced the desired effect and the attacks of the Bavarians on their right flank allowed the Wurttembergers to retake La Giberie and move on to take Petit Mesnil against obstinate French resistance. The cavalry performed rather better than the infantry and conducted some successful charges against the French cavalry until the action ended in the darkness. Ground And Deployments

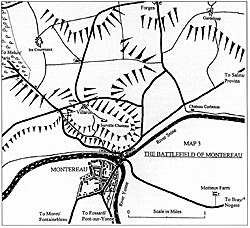

The town of Montereau had a population of 4000 and lies on the confluence of the rivers Seine and Yonne, with bridges over both. The Seine flows approximately east to west at this point and the Yonne joins it from the southeast. The ground south of the Seine is low and flat and contrasts sharply to the north bank which rises very steeply to the plateau of Surville. The plateau is just over 200 feet above the level of the river giving it a very dominant position over the town which lies almost exclusively on the southern (or left) bank. On the plateau overlooking the town is the Chateau of Surville, this was to be the key to the battle. Steep ground lies on three sides of the plateau, which is little more than a kilometre square, making a force stationed on it extremely difficult to outflank. North of the Surville plateau the ground rises very gently but drops away, equally gently, to east and west. The plateau offered the Crown Prince of Wurttemberg a strong defensive position which could be held by the relatively small number of troops he had available against what would ultimately be a larger force. The 'neck' of the plateau could be held, strengthened by the small village of Villaron (now called les Ormeaux) and the Chateau, with any outflanking movements being so difficult because of the terrain that sufficient time would be available to either withdraw or develop a counter move. By far the most daunting prospect must have been the possibility of having to withdraw under pressure. The position was ideal for imposing delay but the requirement to choose the critical moment to break contact, whilst leaving sufficient time to allow all the troops on the north bank to file across two bridges in an orderly manner, must have filled the Crown Prince with trepidation. However, his orders were explicit and he clearly understood the threat to I Corps if he failed to deny the bridges to the French. We can expect that he was under no illusions as to the potential catastrophe that faced him; the list of successful battles fought with a major obstacle directly to one's rear is uncomfortably short! The Crown Prince placed about 8500 infantry, 1000 cavalry (15 battalions and 9 squadrons) and 26 guns on the north bank, any more would have served little practical purpose and exacerbated the problems of withdrawal; in any case there would have been little room to deploy them. The exact deployment is not absolutely clear in any of the sources I have available but there are several good indicators (see Map 4). We know that one brigade was deployed on the left around Villaron and the vineyards about it, extending to cover the road from Paris/Melun; this had two battalions in the village itself. Schaefer's Austrian brigade held the centre based on the Chateau and its grounds and the right was covered by another brigade across the road from Salins on the low ground below the plateau. We also know it was the brigade of Hohenlohe that stood in reserve in the suburbs of Montereau east of the Yonne near the farm of Motteux and that one of its battalions provided the guard force for the bridges, with troops deployed on both banks. It is natural to assume that the brigade from the I Corps was probably behind the town on the west bank of the Yonne. We are also told that the two batteries from I Corps were deployed south of the Seine with one supporting each wing. The Wurttemberg cavalry north of the Seine operated on the left flank and the location and numbers suggest that it was the cavalry of the advance guard: I have therefore assumed that the forward left infantry brigade was also that of the Advance Guard. This would mean that the brigade on the right flank was that of von Doring. The Wurttemberg cavalry brigade deployed with Hohenloe giving a total of 3000 Wurttembergers south of the Seine. More Montereau

Battle of Montereau: Opposing Forces, Ground, Deployments Battle of Montereau: The Battle Battle of Montereau: Order of Battle Revised With New Information (FE51) Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #45 Back to First Empire List of Issues Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List © Copyright 1999 by First Empire. This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com |

The strength of the French forces engaged at Montereau increased steadily as the 18th Feb wore on and Napoleon realised that his attempts to gain other crossings, particularly at Bray, were likely to fail.

The strength of the French forces engaged at Montereau increased steadily as the 18th Feb wore on and Napoleon realised that his attempts to gain other crossings, particularly at Bray, were likely to fail.