Reglement für die Königl. Preuß. leichte Infanterie 1788

The Prussian Reglement 1788 was, apparently, essentially the same for line and light infantry; I have only seen that of the latter. Published approximately six months apart, the light infantry regulation included additional instructions special to arm, such as the deployment of Fusiliers in two ranks rather than three. Under the Reglement 1788 the battalion consisted of four companies, each of which were divided into two pelotons of two züge each. [18] Although the fusilier and grenadier battalions retained four companies, the musketeer battalion was increased to a five company structure in 1799. Two cadences were specified, the Ordinair Schritt and Geschwind Schritt of 75 and 108 paces to the minute respectively but the latter was specified for all evolutions, as discussed at length in an earlier article.

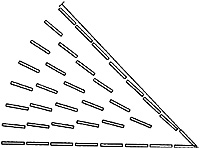

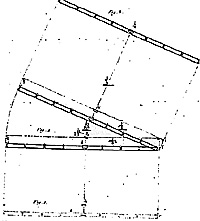

Wheeling is discussed at length, be it in column or line. [19] The manoeuvre is done in the familiar way using a stationary pivot and needs no further description. Wheeling a battalion in line, however, was conducted with moving pivots and appears to be very like the quick wheeling manoeuvre of the 1750s described by Nosworthy. The wheel with a stationary pivot in 1788 was essentially the same as that in 1812, which was described above. Although no precise instructions are given for use of a moving pivot in the Reglement 1788, this unit level manoeuvre demonstrates that it must have been used. Unfortunately none of the Prussian regulations include diagrams of the evolutions and one is restricted to the text and my sketch.

Wheeling with a Moving Pivot - Wie mit einem Bataillon die Schwenkung geschehen soll

(How Wheeling with a Battalion is conducted). [20]

When the battalion wheeled to the right, for example, the commanding officer gave the cautionary command

"Bataillon!", followed by "Rechts schwenkt euch!" ("Battalion!", Right wheel dress!").

On receipt of the command "euch!" ("dress!"), officers commanding stepped two paces out from their pelotons. The first zug, on the right of the line, then executed an 'eyes left', the remainder an 'eyes right'. On receipt of the executive command, "Marsch!" all züge stepped off at the Geschwind Schritt.

The first zug wheeled right with a stationary pivot into the new alignment where it halted on the order of its of officer commanding and adjusted dressing, executing an 'eyes right'. "Halt!" "richt euch"! ("Halt!" "right dress!").

He then adjusted the alignment of the first zug precisely on the 'point de vue' for the left flank, established before the manoeuvre commenced, probably being marked by an officer who would have ridden out to give the battalion the reference point.

The remaining züge did not wheel on the spot, but stepped off holding their right flanks back during the march, whilst the left flanks moved. In this fashion each zug was gradually wheeled on a moving pivot, one after the other, into their places on the alignment marked by the first zug. Once in the alignment they were given the order,

"Halt!" "richt euch!" The eyes remained to the right and officers commanding adjusted their züge on the 'point de vue' of the left wing.

The Reglement 1788 goes on to say, in the event where no 'point de vue' was marked for the left wing, that as each zug arrived at four or five paces from the alignment, each individual officer commanding, placing himself on the left, dressed his own zug into the new alignment on the peloton to its right. The alignment of the battalion was then dressed on the right.

Instruction for the Infantry 1798.

After the death of Frederick the Great, the Prussian army declined, of that there is no doubt. Frederick William III wrote thus in his Instruction for Infantry 1798.

The Instruction points out that wheeling a line of battalions was similar to that of a single battalion in line,

"In all cases this movement is nothing more than performing in large bodies which dress by their respective Colours, that which is done in the Change of Front by the Echelon march of Sections: that is to say each battalion traverses the space betwixt the old and the new alignment as precipitant, otherwise the outflankings would be too great, the intervals would be lost and in a considerable wheel that is of 90 degrees the battalions would stand one behind the other which must be avoided. The 1st battalion only must be permitted to perform at once the whole intended wheel, so as to mark the base for the others, the rest incline successively until they see clearly that they have gained their proper intervals and by this method movement in Echelon of Battalions is necessarily formed".

In the context of wheeling a line it also explains that the stationary pivot was

"slower because the pivot does not at first move from the spot, and the wheeling flank comes round in cadence." [23] The moving pivot was, quite clearly, known to the Prussians at least as early as 1798 and there is sufficient evidence in the Reglement 1788 to demonstrate that it was known earlier still.

Instruction zum Exerciren der Infanterie 1809 and Exercir Reglement für Infanterie de Königlich Preussen Armee 1812

The Instruction 1809 retained the Ordinair and Geschwind Schritt of 75 and 108 paces to the minute respectively, but also describes an unnamed cadence of 120 paces to the minute to be used for all evolutions. [24]

The Ordinair Schritt and Geschwind Schritt were also unchanged under the Exercir Reglement 1812, which specifies the latter for all evolutions. Although I have found no mention of a 120 pace to the minute cadence in the latter document, it should be remembered that a number of interim instructions were promulgated between the publication of the Reglement 1788 and the Exercir Reglement 1812.

It is my understanding that elements of the earlier instructions and the Reglement 1788 still applied and that the Exercir Reglement 1812 was complementary, rather than a complete replacement, being written with the assumption of a degree of knowledge. [25] Although I have no documentary evidence of the status of the 120 pace to the minute cadence in 1812, the likelihood that the Instruction 1809 still applied in this context should not be discounted. Be that as it may, by 1812 the Prussians, like the French, changed direction either by forming or wheeling. Their methods were very similar. Under the Reglement 1812, a Prussian battalion consisted of four companies, each of two züge. The term 'Peloton' used to describe the half company sub-unit under the Reglement 1788 was dropped. [26]

Wheeling with a Moving Pivot - Schwenkungen während des Marches (Wheeling during the March). [27]

The manoeuvre was executed with a moving pivot. The cautionary order was "Rechts (Links) schwenkt" ("Right (Left) Wheel"), with the executive "Marsch!" given on arrival at the pivot point.

Movement and contact was carried out as described for Schwenkungen von der Stelle, elbows touching and so on, the wheeling flank bringing the ranks round. The pace was shortened towards the pivot flank and the pivot moved from the pivot point "completely free", so that it became vacant for the succeeding rank. On completion of the manoeuvre the command, "Gerade aus!" ("Straight ahead!") was given and the unit marched on maintaining cadence. This manoeuvre is essentially the same as that conducted by the French when wheeling with a moving pivot, but the ranks do not bend.

Forming - Aufmarsch aus Reihen Durch Auflaufen der Rotten (Deploying from Files through Forming the Ranks). [28]

Compare the French method (if you'll pardon the expression) with the Prussian method (the mind boggles!). The cautionary was, "Rechts, (Links) marschirt auf" ("Right, (Left) march"), upon which the pivot marched out onto the new alignment. The executive "Marsch!" was the signal for the remainder to fall in on the marker in essentially the same fashion as described for the French above. Dressing was taken from the right "Augen rechts!" ("Eyes right"!) The influence of the French practice is evident in the Reglement 1812.

Wheel Continued

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. A diagram of the manoeuvre is at Illustration 11, at left. A battalion wheel to the left was performed in similar fashion. The importance of dressing during changes of direction in line is also very evident. Variations on this theme for wheeling lines are found in all regulations under discussion in this article, including a central manoeuvre where one wing advanced whilst the other retired, the line revolving about the centre, which will be examined later.

A diagram of the manoeuvre is at Illustration 11, at left. A battalion wheel to the left was performed in similar fashion. The importance of dressing during changes of direction in line is also very evident. Variations on this theme for wheeling lines are found in all regulations under discussion in this article, including a central manoeuvre where one wing advanced whilst the other retired, the line revolving about the centre, which will be examined later.

An eight peleton French battalion conducting a change of direction to the right using a similar manoeuvre, taken from the French Règlement 1791, is shown at Illustration 12, at right. [21]

An eight peleton French battalion conducting a change of direction to the right using a similar manoeuvre, taken from the French Règlement 1791, is shown at Illustration 12, at right. [21]

"In the many opportunities I have had of observing the Army closely I have perceived a number of differences which exist, not only between the several Inspections (which often vary so widely in principle from each other, that they do not seem to belong to the same service) but even in some Inspections betwixt the regiments which compose them." [22]

Introduction

Life Before Cadence

Wheeling With a Stationary Pivot

Wheeling With a Moving Pivot

The Regulations: France

The Regulations: Prussia

The Regulations: Austria

The Regulations: Britain and KGL

Summary and Conclusions

Footnotes

[18] Ibid. p14 and p68.

[19] Reglement für die Königl. Preusß. leichte Infanterie. Berlin, 1788. pp66-105.

[20] Ibid. p100.

[21] Règlement 1791. op. cit. Ecole de Bataillon, Planche XXII.

[22] Instruction for the Infantry 1798. Manuscript translation. n.d. p1.

[23] Ibid. p27.

[24] Instruction zum Exercieren der Infanterie. Königsberg, 1809. pp8-9.

[25] Hofschröer, Peter. Prussian Line Infantry, 1792-1815. London, 1984. p10. Normally I would hesitate to quote from any of the Osprey - Men at Arms Series on the Napoleonic period. Together with Bryan Fosten, however, Hofschröer is one of two authors of this series who write reliably on Napoleonic subjects.

[26] Exercir Reglement 1812. op. cit. p44

[27] Ibid. pp39-40.

[28] Ibid. p37.

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #28

© Copyright 1996 by First Empire.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com