Wheeling with a stationary pivot remained in the repertoire of all armies throughout the Napoleonic period and beyond. In general terms, the pivot would execute a turn on the spot towards the new direction. The ranks would then close up so that there was the smallest distance possible between them, and wheel round onto the new alignment. Having done so, they returned to rank distance, typically one pace, adjusted dressing and moved off. There was, however, one absolutely vital difference between the way a wheel with a stationary pivot was conducted in 1812 and the way in which it was conducted in 1712. Although we will discuss it in a moment this covers the essentials of wheeling with a stationary pivot.

Under the Prussian Exercir Reglement 1812, for example, it was accomplished thus. Throughout this article, as usual, I have given the orders in their original together with an interpretation, rather than a literal translation.

Wheeling with a stationary pivot - Schwenkungen von der Stelle (Wheeling on the Spot) [5]

The cautionary command was, "Mit Zügen [6] rechts (links) schwenkt."

("By zügen, right (left) wheel") followed by the executive command, "Marsch"! upon receipt of which the sub-unit stepped off towards the flank indicated at 108 paces to the minute.

The regulations warn against stamping the feet or bending the knee too much, the inference of which is that bending the knee to a degree was allowed. The step was progressively shortened towards the pivot until the man on the pivot point itself actually stood still. Each man lightly touched his neighbour on his pivot flank with the elbow to maintain contact, and to resist pressure from that direction. Heads were turned towards the file on the pivot flank as they marched in order to maintain dressing. Once on the new alignment the executive command

"Halt!" was given and the sub-unit dressed on its markers.

Cadence and close order

The difference, alluded to above, between drill as it was conducted in the early 18th Century and generally from about 1740 onwards, was cadence, or marching to a regular tempo. The benefits of this innovation have been discussed at length in an earlier article, but briefly it was cadence that allowed close order marching, which made dressing easier to maintain and, thus, the entire process of tactical manoeuvre faster.

The discovery of cadence marching, the tempo typically provided by drum beat, is usually attributed to Comte Maurice de Saxe although perhaps rediscovery might be more accurate as I believe it is true to say that the Romans used cadence. Nevertheless, as late as 1732 it had not been adopted by any major European army, indeed, the French did not do so universally until as late as 1749. [7] It is also generally accepted that the Prussian army was the first to adopt the practice in modern times, usually credited to Leopold of Anhalt-Dessau, sometime prior to 1740. [8]

So, it is now approximately 1750 and as far as wheeling is concerned, one of its most important utilities, if not the most important, is in conducting parallel deployment from open column which has been discussed at length in previous articles. In all major armies wheeling has been made easier and faster to accomplish due to the effects of cadence and although the pivot remains stationary, wheeling is now conducted with ranks closed up.

Wheel Continued

[5] Exercir Reglement für Infanterie der Königlich Preussen Armee. Berlin, 1812. pp38-39.

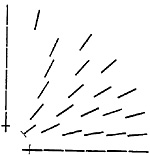

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. At about this time the Prussians are credited with a quick wheeling manoeuvre, designed to enable a deployed battalion to wheel as fast as possible towards a developing threat. In this manoeuvre a file, or number of files, even an entire company, on the pivot flank would be marched out of the battalion, halted and dressed on the new alignment. The rest of the battalion then marched in an arc onto the new alignment where it dressed on the files marched out previously. [9] The manoeuvre is shown at right. This process of marching files out from the battalion to mark the new alignment is similar, albeit on larger scale, to the forming manoeuvre described in the French Règlement 1791.

At about this time the Prussians are credited with a quick wheeling manoeuvre, designed to enable a deployed battalion to wheel as fast as possible towards a developing threat. In this manoeuvre a file, or number of files, even an entire company, on the pivot flank would be marched out of the battalion, halted and dressed on the new alignment. The rest of the battalion then marched in an arc onto the new alignment where it dressed on the files marched out previously. [9] The manoeuvre is shown at right. This process of marching files out from the battalion to mark the new alignment is similar, albeit on larger scale, to the forming manoeuvre described in the French Règlement 1791.

Introduction

Life Before Cadence

Wheeling With a Stationary Pivot

Wheeling With a Moving Pivot

The Regulations: France

The Regulations: Prussia

The Regulations: Austria

The Regulations: Britain and KGL

Summary and Conclusions

Footnotes

[6] Dative case. Plural forms end in 'n'. Thus Züge and zügen are both plurals of zug. This sub-unit is usually translated as a platoon in modern English but I have retained the original German in this article so as not to confuse it with French Peletons and British Platoons which were company size sub-units at this period. In this Prussian example the zug is a half-company size sub-unit, the Austrian zug, however, a zug is a quarter-company size. Anyway if I slip into the wrong case from time to time and refer to zügen when I mean züge, but really mean 'zugs', I place the blame entirely on the German language with its wretched case sensitivity. At least the French are civilised enough simply to bung an 's' on the end regardless. In an ideal world, of course, everyone would speak English.

[7] Lloyd, EM, Col. A Review of the History of Infantry. London, 1908. p156.

[8] Lloyd. ibid. p156.

[9] Nosworthy, Brent. The Anatomy of Victory. New York, n.d. pp252-253.

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #28

© Copyright 1996 by First Empire.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com