When discussing the science of 'Napoleonic warfare', of which drill is a part being conducted according to an exact system of rules (tactics are an art in comparison being the application of ingenuity, initiative and imagination and are only limited by parameters such as skill, cunning and circumstances, none of which are constant), it becomes abundantly clear that with even so apparently simple a subject as wheeling one cannot confine oneself to that period alone. The means by which units were moved, deployed in line or formed in column, were largely unchanged from the methods of the preceding half-century. To return to the matter in hand, however, first we need to return to the early part of the 18th Century. At about that time there were only two methods of wheeling, both of which were executed on a stationary pivot.

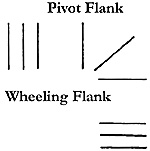

The first was by individual ranks and required a stationary pivot flank whilst the rank stepped progressively shorter the closer it was to the pivot flank, until the rank had been brought round into the new direction. At this point it would adjust its dressing and move off. The next rank took its place on the pivot point and conducted the same manoeuvre, and so on until the entire sub-unit had changed direction.

Next time you pass through one of those large revolving doors on your way into the local Safeway, or whichever hypermarket you prefer, watch the leaf of the door as it moves round the central spindle and you will understand the relationship of a wheeling rank (the leaf) to its stationary pivot (the spindle). It will also be apparent that using this method only one rank was able to wheel at a time because the pivot point remained occupied. This meant that wheeling with a stationary pivot was a processional manoeuvre.

For example, if a rank arrived on the pivot point before the preceding rank had completed the wheel, it simply had to wait its turn. Where ranks were deployed in open order, however, which was universal at the time, it was possible that the preceding rank would clear the pivot point and move off, before the succeeding rank had closed the interval. This was fine in theory, but, without cadence, difficult in practice. This is shown at right.

For example, if a rank arrived on the pivot point before the preceding rank had completed the wheel, it simply had to wait its turn. Where ranks were deployed in open order, however, which was universal at the time, it was possible that the preceding rank would clear the pivot point and move off, before the succeeding rank had closed the interval. This was fine in theory, but, without cadence, difficult in practice. This is shown at right.

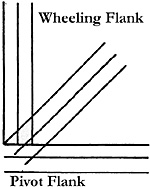

The second method could be used by the sub-units of a battalion. In this manoeuvre the procedure was similar except that the entire sub-unit wheeled on a stationary pivot, that is to say all ranks at the same time. The front rank wheeled as described above whilst those in the subsequent ranks, in order to keep the ranks directly behind one another, followed their file leaders moving towards the wheeling flank as they did so until the entire sub-unit had been brought round into the new direction.

Once having done so it dressed and moved off, and the following sub-units conducted the same manoeuvre in succession on the same pivot point, one after another until, ultimately, the battalion column was turned towards the new direction. This is shown at Illustration 2 at left and above.

Once having done so it dressed and moved off, and the following sub-units conducted the same manoeuvre in succession on the same pivot point, one after another until, ultimately, the battalion column was turned towards the new direction. This is shown at Illustration 2 at left and above.

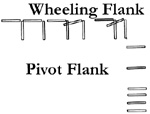

As before, however, if the wheeling sub-unit did not complete the manoeuvre in the time that the succeeding one took to close the interval, it was a case of "hurry up and wait" for the latter. Furthermore, whilst the succeeding sub-unit waited its turn, the sub-units behind it would also be closing the interval, rather like the bellows of an accordion. Similarly, should the wheeling sub-unit complete the wheel early, the interval between it and the succeeding sub-unit would open up, the effect could, therefore, be reversed.

A similar phenomenon would also affect the intervals between preceding sub-units. The penalty was subsequent confusion because, having completed the manoeuvre, the sub-units might all be at different intervals. Now, in order to conduct parallel deployment it was absolutely vital that the correct deploying distances between sub-units be maintained and in order to maintain deploying distance, wheeling by individual sub-units had to be carried out in the correct time, exactly, no more - no less. Since the very purpose of maintaining deploying distances was to enable a column to deploy, it was essential that they be correct, and the magnified effect on an entire column of battalions wheeling subsequently to form line of battle in parallel deployment, that is to say into line by a simultaneous quarter wheel of sub-units to a flank, is clear enough.

The consequences for deployment of sub-units too close, or too far apart, is a magnification of the effect described in an earlier article discussing file frontages and depths, and further serves to illustrate how vital it was for deployment purposes to maintain correct distances, be they between individuals, sub-units or battalions. The consequences of the failure to maintain intervals is shown at right.

The consequences for deployment of sub-units too close, or too far apart, is a magnification of the effect described in an earlier article discussing file frontages and depths, and further serves to illustrate how vital it was for deployment purposes to maintain correct distances, be they between individuals, sub-units or battalions. The consequences of the failure to maintain intervals is shown at right.

It is also obvious that wheeling on a large frontage had other implications. The length of pace that soldiers could take on the wheeling flank was limited by human anatomy. Seven league boots are the stuff of fairy tales. This was partly overcome by having the pivot move, maintaining the cadence but stepping short whilst the wheeling flank maintained the cadence and normal pace or, as in the case of the British for example, stepping out to 33 inches. There was, nevertheless, a limit to the frontage of a wheeling sub-unit or unit beyond which it was simply not possible to conduct such a manoeuvre.

As an aside, although the style of marching has changed since the early 19th Century, to give some idea of how fast Napoleonic infantry moved take a look a the Trooping the Colour ceremony next time it is on the TV. The British Army's quick march is 120 paces to minute. For those readers who watched the march past the Cenotaph in Whitehall on TV last Remembrance Sunday, that is conducted at 100 paces to the minute. It is slowed deliberately to take account of the advancing years of many of the veterans who take part. It is, however, just about as fast as most Napoleonic infantry marched most of the time.

Wheel Continued

-

Introduction

Life Before Cadence

Wheeling With a Stationary Pivot

Wheeling With a Moving Pivot

The Regulations: France

The Regulations: Prussia

The Regulations: Austria

The Regulations: Britain and KGL

Summary and Conclusions

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #28

© Copyright 1996 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com