Tactical Examples

Krieg 1809, a secondary source albeit highly regarded, has a number of accounts of regiments forming in divisions. Interestingly it does not always specify divisions-massen, from which it is possible to infer division columns open to one degree or another. Of particular interest is an account of an action involving the three battalions of Infanterie Regiment Nr 49 Kerpen,

"Deployment was not possible on a wide frontage because of the undergrowth and broken terrain. The first battalion was divided into three columns each of two companies. The first division advanced on the right in order to attempt to take the Hubertus dam. The second division advanced through the centre of the island under command of Major O'Brien. The third division advanced beside the right bank of the Schwarzen Lacken. The direction of the advance was towards the Jagerhaus. The divisions were formed in half company columns which advanced abreast of each other."

"The second battalion formed the second echelon in three division columns like the first. The third battalion comprised the third echelon formed in two columns of three companies each." [39]

The first and second battalions are clearly formed in separate division columns and although no mention is made of divisions-masse I suspect that it is likely this is what is being alluded to. They are clearly tactically independent of each other and seem to have different objectives, but appear to be mutually supporting, as laid down in the Reglement 1807 for divisions-massen. The use of division columns in this case seems to be a result of terrain factors rather than cavalry threat. The third battalion is clearly at war strength of six companies but this time it is formed into two tactically separate half-battalions, apparently on half-division (company) frontage.

It is, nevertheless, convincing enough, for it conforms to the deep formations typical of Napoleonic doctrine, and contrasts with the shallow linear doctrine of the previous century. It also compares with the attacking formations for Brigades illustrated in the Prussian Reglement 1812, [41] in which, it is interesting to note, at least one of the available fusilier battalions was divided tactically into half-battalions.

The description of Austrian half-battalion columns is particularly interesting because it confirms that they were used as a tactical formation and there are further examples, sufficient to suppose that this was not unusual. Unfortunately we are not told if these were closed in masse or not.

There are other examples in this work which describe the use of division columns not specified as massen. Is this an oversight and should they all be described as massen? Did the Austrians use division columns with sub-units open to one degree or another? I don't know to be frank but what is clear is that these division columns operated separately from each other, appear to have had separate objectives sometimes and even deployed their third ranks as skirmishers, as prescribed by the Reglement 1807.

"Eventually the third rank of these two divisions were used to prolong the skirmish line of the Grenz and Jager." [42]

The apparent use of divisions as tactically separate entities is almost a precursor of the company column, which appeared in the Prussian repertoire later in the 19th Century, and is especially interesting because I am not aware of sub-unit tactics of this kind, being used on this apparent scale by any other nationality during the period. Except for the purposes of skirmishing generally, where they were used to support those deployed on the skirmish line, the tactical use of sub-units independently does not seem to have enjoyed the popularity that seems to be the case here.

What I am not sure about is whether it has been established is that the Austrians had a unique tactical doctrine or not, or if these actions were described because they were unusual, and, therefore, worthy of special note for that specific reason. The latter is always a possibility and one must be careful when interpreting any information because if what one has are examples of the exception, rather than the rule, there is a danger that the process of converting information into a picture of what took place might arrive at a totally flawed picture, in this case of Austrian tactical doctrine. On the other hand Krieg 1809 is replete with such descriptions to suppose that the entire repertoire of the Reglement 1807 was in use, including the frequent employment of the divisional sub-unit.that the process of converting information into a picture of what took place might arrive at a totally flawed picture, in this case of Austrian tactical doctrine.

On the other hand Krieg 1809 is replete with such descriptions to suppose that the entire repertoire of the Reglement 1807 was in use, including the frequent employment of the divisional sub-unit.

Bearing in mind many of the critical things that have been said about the Austrian army during this period some of which, operational command and control for example, are probably justified, I hesitate to credit it with a tactically innovation doctrine which was either markedly modern or different. That, on the other hand, seems to be exactly what is emerging from this very brief overview. Have we another Napoleonic myth on our hands here? I would certainly not want to be responsible for creating one and would welcome comment and further research on the matter.

That, in admittedly simplistic terms, is it. Simplistic because I have only looked at the essentials and there remain conversions not discussed at all. I have also not given much attention to the activity going on in the background, where commands are being received and given by other officers, NCOs, and so on, who have to move from place to place within the unit relative to the conversion taking place, and the formation it is in.

In general terms, however, the Austrians went about their business much as everybody else did, albeit with some variations on well worn themes. The only unique feature is the divisions-masse which although, as far as I am aware, was not used elsewhere is sufficiently different to merit special attention.

Both the Exercier-Reglement 1807 and Abrichtungs-Reglement 1806 are essentially Prussian in nature. This should not be construed as criticism nor come as a surprise for it is a matter of fact that every single regulation used during the Napoleonic period, including the French, reflected the drill methodology established by the Prussians during the latter half of the 18th Century. Thus, the oft quoted critical remark from Krieg 1809 about the Exercier-Reglement 1807 being "Frederican" in nature, whilst certainly true, is hardly fair either in this context or comparison with its peers. On the other hand, we have seen that the Austrians were certainly capable of tactical innovation.

[1] Rothenberg, Gunther E. Professor. Napoleon's Great Adversaries, The Archduke Charles and the Austrian Army 1792-1814. London, 1982. p87.

More As You Were

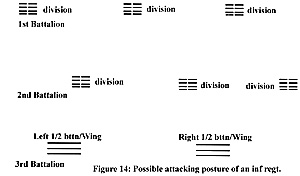

Dave Hollins has also provided me with evidence from the same source, describing deployments generally, which states that distance between echelons was approximately three battalions deep and that they were usually drawn up in a 'chequer board' fashion to provide a killing zone, with artillery in the gaps between the columns. [40] Extrapolating all this information, and assuming that sufficient frontage would be used to deploy into line if necessary, an illustration of what a typical Austrian infantry regiment in attacking posture might look like is at Figure 14.

Dave Hollins has also provided me with evidence from the same source, describing deployments generally, which states that distance between echelons was approximately three battalions deep and that they were usually drawn up in a 'chequer board' fashion to provide a killing zone, with artillery in the gaps between the columns. [40] Extrapolating all this information, and assuming that sufficient frontage would be used to deploy into line if necessary, an illustration of what a typical Austrian infantry regiment in attacking posture might look like is at Figure 14.

Summary

References:

[2] Wagner, Watler. Von Austerlitz bis Königgrätz. Österreichische Kampftaktik im Spiegel der Reglements 1805-1864. Osnabrück, 1978. pp7-11

[3] Abrichtungs-Reglement für die k. und k. k. Infanterie 1806. Wien, 1806. p16-19

[4] Ibid. pp19-20.

[5] Rothenberg. op.cit. p110 and Nafziger, George. Austrian Infantry Maneuvres. Empires, Eagles and Lions No104. p10.

[6] Abrichtungs-Reglement 1806. op.cit. p119.

[7] Exercier-Reglement für die k. k. Infanterie 1807. Wien, 1807. pp4-5.

[8] Règlement Concernant l'Exercice et les Manouevres de l'Infanterie de Premier Août 1791, Paris, n.d. Formation d'un Régiment en Bataille, p3.

[9] Exercier-Reglement 1807. op.cit. p4

[10] Duffy, Christopher. The Army of Maria Theresa, The Armed Forces of Imperial Austria 1740-1780. London, 1977. p63.

[11] Rothenberg. op.cit. pp24-25.

[12] Ibid. p87.

[13] Exercier-Reglement 1807. op.cit. pp3-4.

[14] Rothenberg. op.cit. p109.

[15] Exercier-Reglement 1807. op.cit. pp9-10.

[16] Ibid. p74.

[17] Ibid. p78.

[18] Abrichtungs-Reglement 1806. op.cit. pp107-115.

[19] Exercier-Reglement 1807. op.cit. p80.

[20] Nafziger, George. Austrian Infantry Maneuvres.

Empires, Eagles and Lions No104. pp10-17.

[21] Exerzir-Reglement für Infanterie der Königlich Preußischen Armee. Berlin, 1812. pp70-71.

[22] LLoyd. E.M. Colonel. A Review of the History of Infantry. London, 1908. p181.

[23] Exercier-Reglement 1807. op.cit. pp83-84.

[24] Planche VIII, Figure 2, p21 and Ecole de peloton par. 182.

[25] Abrichtungs-Reglement 1806. op.cit. pp138-153

[26] Exercier-Reglement 1807. op.cit. p85.

[27] Jeffrey, George. Tactics and Grand Tactics of the Napoleonic Wars. Brockton MA, 1982. pp43-44.

[28] Exercier-Reglement 1807. op.cit. pp84-85.

[29] Rothenberg. op.cit. p110.

[30] Exercier-Reglement 1807. op.cit. pp89-92.

[31] Ibid. p89.

[32] Abrichtungs-Reglement 1806. op.cit. p17.

[33] Exerzir-Reglement 1812. op.cit. p84.

[34] Exercier-Reglement 1807. op.cit. p86.

[35] Ibid. pp92-96.

[36] Rothenberg. op.cit. p111.

[37] Nafziger. op.cit. p14.

[38] Exercier-Reglement 1807. op.cit. p221 and p229.

[39] Krieg 1809. Wien 1907-1910. Vol IV. p302.

[40] Ibid. p710.

[41] Exerzir-Reglement 1812. op.cit. Plan No 11.

[42] Krieg 1809. op.cit. p244.

Introduction and Battalion Organization

Column, Masse, and Breaking

Deploying

Tactial Examples, Footnotes

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #25

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com