In my article on columns and lines in FE 16/17, I made an error in the section dealing with the Austrian army. Although the methodology is essentially correct, it is in need of amendment. The fault is entirely mine and results from confusing the half-company with the zug. Only Allah is perfect, as they say. Perhaps I could double round the parade square in full marching order for a couple of hours by way of recompense. Instead of two hours at the doublirschritt, resultant Athletes Crotch, Jogger's Nipple, and other sweat induced nasties perhaps I might offer, not merely a complete revision, but a detailed expansion of my original generalised notes. I would like to thank Dave Hollins for casting a critical eye over it.

Austrian Column to Line Evolutions the Second!

As far as the Exercitium für die sämmentliche Kaiserlich-Königlichen Infanterie, Generals-Reglement 1769 is concerned, I think my remarks are still valid although without seeing it, they remain conjecture. The usual cadence seems to have been 75 to the minute which was retained under Mack's Instructionspunkte, although he was, apparently, responsible for the introduction of the 120 pace to the minute cadence for evolutions. [1]

Wagner does not specify the cadence in his comparison of the Exercier-Reglement 1807 with the Generals-Reglement 1769 although he notes, however, that both documents are of similar length and contain essentially the same basic instructions, a noticeable difference being the introduction of Massen and instructions for skirmishing. [2]

It is undoubtedly fair to suppose that the Generals-Reglement 1769 was Prussian in all but name and doubtless parallel deployment was the most commonly used tactical method, that is to say deployment from a column open to full interval, to the flank of the column, as illustrated at Figure 16 of the original article. The parallel method of deployment was well known, of course, and in the repertoire of all nationalities, indeed, it was the standard method of deployment throughout the 18th Century. In the context of Wagner's remarks, however, it would seem incautious to assume that perpendicular deployment was unknown in the Austrian service prior to 1807. Indeed, if this was the case, it would actually make the Austrians unique. Without sight of the Generals-Reglement 1769, however, further comment is not really useful. That leaves the Exercier-Reglement 1807.

What I propose to do is examine certain parts of this document in the context of column to line evolutions, particularly massen, where some controversy is evident. I should make it clear at this point that all regulations of the period were long, complex and comprehensive documents and I make no attempt whatsoever to describe every single evolution described within the Exercier-Reglement 1807, even within the confines of column to line conversions. To put this in context, there are 251 pages of small Gothic script in total, arranged in three chapters containing 26 sections, each of which deals with a specific group of conversions or instructions and although I have the complete text, I do not have the illustrations which can make understanding it somewhat difficult at times. Be that as it may, an analysis of the entire document is not possible, not by me so long as I have the day job anyway, and a degree of selectivity is called for, for which reason I will confine myself to those parts that seem, to me, to be most important.

I have also included the actual commands where appropriate, in order to demonstrate the difference between the cautionary and executive, that is to say those commands that prepare the soldier for what is to come, and those that tell him to do it. Executive commands are shown in italics.

The first part of the Exercier-Reglement 1807 is the Army Order of 15th March 1807, which makes it very clear that the Abrichtungs-Reglement für die k. und k. k. Infanterie 1806 (Training Regulation) was the principal training tool for the soldier, like the sections entitled Ecole du Soldat and Ecole de Peloton in the French Règlement 1791 and the British Manual and Platoon Exercises, and frequent reference is made to it. It is in the Abrichtungs-Reglement 1806 that one finds all the basic methods of instruction for recruits, together with length of pace, 2 schuh (approximately 12 Imperial inches to a schuh), numbers of paces pe minute and so on, in which context two cadences are specified. [3]

The doublirschritt of 120 paces to the minute was used for all conversions, and whenever speed was important, and was considered

Other sources, which I quoted in the bibliography to my original article, make mention of a 105 pace to the minute cadence, referred to as either the "manoeuvre" pace or "Geschwindschritt", [5] and although it is always possible that I've missed something, I have yet to find this cadence reflected in either the Exercier-Reglement 1807 or the Abrichtungs-Reglement 1806.

The ranks within sub-units marched at rank-distance and this presents a problem for the two documents do not appear to agree

The Exercier-Reglement 1807 on the other hand, having established that three ranks was the normal formation, states,

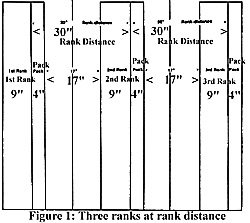

Are there two different rank distances? I really don't know. Personally, however, I prefer the latter because the former appears far too open for most purposes. If we call the pack 4 inches deep, like the French, and estimate the space taken up by the soldier himself as approximately 9 inches and take this from 30 inches, we are left with approximately 17 inches from the chest of the men in one rank to the pack of the men in front.

No frontage is given for a file except to say,

Since a soldier ought to occupy roughly the same space regardless of whether he is in ranks facing to his front or in files facing to a flank, otherwise the length of a columns of files would not equal the frontage of the sub-unit it was formed from, with all the implications for re-deployment into line, it would seem that the file frontage should also be approximately 30 inches. I concede, however, that this is speculative and seems rather wide, but then the rank distance, which is specified at 30 inches, is also somewhat greater than found elsewhere.

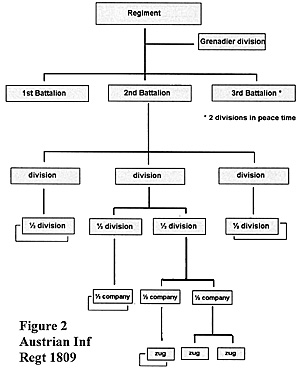

Let me now rectify the fundamental blunder in my original article. A half-division or company contained four züge, not two züge as stated in my earlier article. It would appear that the regimental organisation used through the greater part of the Napoleonic period was originally established in 1769 at two field battalions of six half-divisions (companies) and one garrison battalion of four half-divisions, increased to six in war, and a grenadier division. [10]Rothenberg gives more or less the same organisation as at 1792 except that Hungarian regiments are said to consist of three field and one garrison battalion. [11] Mack's reorganisation of 1805 apparently resulted in a regimental organisation of four fusilier battalions and one grenadier battalion, each of four companies, although the same source expresses doubt that this was ever completely adopted, if at all. [12]

Be that as it may, the three battalion regimental organisation, with grenadier division, is described in the Exercier-Reglement 1807 which further states that the first and second battalions were divided into three divisions, the third battalion into two, although it is my understanding that these were brought up to full strength in war. These were numbered first through eighth division respectively. Each division consisted of two half-divisions, numbered 1st through 16th respectively. Each half-division consisted of two half-companies and each half-company of two züge. [13]

Three Ranks

The Austrians used three ranks although the third was not generally used for musketry, [14] in which context it is worth mentioning that although retained, the use of the third rank for this purpose was falling into disuse virtually everywhere by this period. The Austrians and Prussians, for example, drew their skirmish element from the third rank, a much better practice than having a specialist sub-unit for two reasons. The first being that it did not disturb battalion symmetry, the second that each sub-unit had its own skirmish capability when deployed individually.

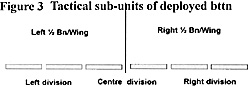

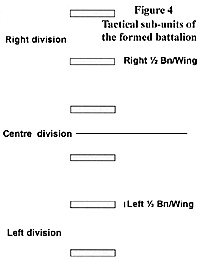

It is also necessary to explain that the battalion was divided tactically into a left and right flank or wing (Flügel), a practice found elsewhere. The right flank consist of the first three half-divisions, the left flank consisted of the last three half-divisions.

The fact that they were not full battalions would not effect the way in which they carried out conversions.

[15] The tactical half-battalion is the probably the source of the three company divisions-masse described in many modern works.

It is also evident that individual divisions could function as independent tactical sub-units. This will be discussed later.

More As You Were

Exercier-Reglement für die Kaiserlich-Königliche infanterie 1807

1. Ordinären Schritt (Ordinary Step) of between 90 and 95 paces to the minute.

2. Doublirschritt (Double Step) of 120 paces to minute.

"essential to the assault, the attack, or fast evolution of the column through deploying, or deploying-march (flank march of files) of the masse, over short distances and time so as not to exhaust the strength of the soldiers." [4]

"The distance from one rank to another is two and a half schuh (approximately 30 Imperial inches), namely from the heels of the front one to the toes of the shoes of the rank behind." [6]

"the distance from one rank to another amounts to two and a half schuh from the heels of the front one to the heels of the rank behind." [7]

An illustration is at Figure 1. This, whilst greater, compares with the French regulations and seems the most likely,

An illustration is at Figure 1. This, whilst greater, compares with the French regulations and seems the most likely,

"The distance of a rank to another will be one pied (approximately 13 Imperial inches), measured from the chest of the men in the second and third ranks to the backs of the men preceding them in their respective files, or his pack when loaded". [8]

"The files are elbow to elbow, lightly closed, the rear men standing exactly behind the men to their front" [9]

Battalion Organisation.

To summarise.

To summarise.

Regiment = 3 battalions (plus 1 Grenadier division detached in war)

Battalion = 3 divisions (3rd battalion 2/3 divisions in peace/war)

Division = 2 half-divisions or companies (the Exercier-Reglement 1807 uses both terms, principally the former, the Abrichtungs Reglement 1806 the latter.)

Half-division or company = 2 half-companies

Half-company = 2 züge

An illustration is at Figure 2.

Thus, when a battalion was in line with the senior company on the right and the remainder in ascending order towards the left, it was divided into left and right flanks at the junction between the third and fourth half-divisions. The third and fourth half-divisions were, thus, the right and left centre half-divisions (companies) respectively. Illustrations are at Figures 3 and 4.

Thus, when a battalion was in line with the senior company on the right and the remainder in ascending order towards the left, it was divided into left and right flanks at the junction between the third and fourth half-divisions. The third and fourth half-divisions were, thus, the right and left centre half-divisions (companies) respectively. Illustrations are at Figures 3 and 4.

The battalion could also be organised into two half-battalions which do appear to have had significant tactical usage, being documented in Krieg 1809. The half battalion consisted of three companies formed from either the right or left wing and I have found neither a statement to the effect that half-battalions could not conduct any of the evolutions described in the Reglement 1807, including closing up in masse, nor special instructions for such units.

The battalion could also be organised into two half-battalions which do appear to have had significant tactical usage, being documented in Krieg 1809. The half battalion consisted of three companies formed from either the right or left wing and I have found neither a statement to the effect that half-battalions could not conduct any of the evolutions described in the Reglement 1807, including closing up in masse, nor special instructions for such units.

Introduction and Battalion Organization

Column, Masse, and Breaking

Deploying

Tactial Examples, Footnotes

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #25

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com