The Column

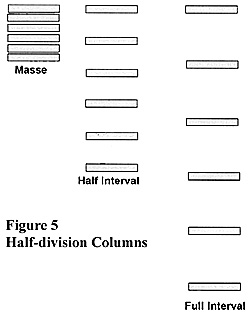

The Austrian infantry battalion manoeuvred in columns open to full distance, half distance or masse (closed) formed on zug, half-company, half-division, or division frontage. Full distance (sometimes called deploying distance, wheeling distance or full interval and similar terms elsewhere) simply meant that the distance between sub-units was equal to their width. A column at half-distance, therefore, marched with the distance between sub-units equal to half their width. In masse the sub-units closed to rank-distance. An illustration is at Figure 5.

The preamble to Section 1 to Chapter 2 deals with the column in general terms, its purposes and so on.

[16]What follows is not an entirely literal translation. Literal translations are more useful as a source of amusement. It is, however, intended to convey what is meant as accurately as I can make it.

"The march in line requires suitable terrain and gives security of movement to the attack, or occasionally for withdrawal under enemy fire."

"The column is the means by which a unit manoeuvres, either demonstrating, seizing ground or striking the enemy."

"The column is produced by breaking the line in files or in sub-units and this is the object of all evolutions, the ultimate aim of which is to arrive at suitable instructions which include how to do so in differences of terrain, position and unforeseen circumstances".

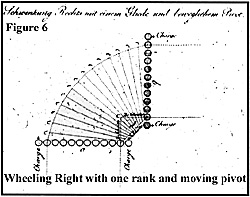

How, precisely, one arrives at instructions for the unforeseen, since one doesn't know, presumably, what they are, eludes me! Be that as it may, paragraph 1 provides an overview of the different methods of forming column from line, such as march of files from the right or left, wheeling sub-units up or down, again from the left or right, and are entirely conventional. Paragraph 2 deals with the detail of marching with the column. Changing direction in column was performed by means of a moving pivot.

[17]

Since the masse was merely a closed column, it was formed on the same sub-unit frontages as the open column but the sub-units themselves were now closed up to rank-distance between them, in the universal fashion, as already described and illustrated. In the context of Gary Will's question about the massen in FE 19, it may be useful to examine the introduction to Section 2 to Chapter 2 in full. [19]

"One uses it to make deployment of the column easier, to defend against impacting cavalry, or also, where terrain permits, to aid the concentration of several units into a small area for purposes of concealment, or to march them concealed and to bring superior forces into action quickly."

"When a mass is formed, not only for these purposes, but with the intention of deployment, it must be manoeuvrable, so the width of its head must be in appropriate proportion to its depth".manoeuvrable, so the width of its head must be in appropriate proportion to its depth".

"The suitable proportion will be when the depth of the mass is the same as its width, or no greater than double the width of its head".

"The battalion will produce a mass of half-divisions (companies) or at least half-companies, every regiment will produce a masse with complete divisions or with sub-units not smaller that half-divisions, and a zug column must, before closing in masse, where other local conditions do not prevent it, first deploy in larger detachments".

This tells us a great deal.

The first thing is that there has been no mention of the divisions-masse. It is evident from earlier discussion, however, that a division was a separate tactical entity, consisting of two half-divisions (companies). I will return to this later on. What we do have, however, is reference to a masse formed from a battalion and also from a Regiment, the latter formed on division frontage. We also know that a masse had functions other than simply protection against cavalry. Concealment and surprise being but two.

Most interesting is the statement that it was used to make deployment easier, which in the vocabulary of the time means into line. The consequences of this are, in theory at least, that Austrian open columns may have closed to massen routinely prior to deploying. The reason for this must have been a matter of time and distance. Deploying from closed column was faster perhaps, and probably less fraught as far as dressing was concerned, since no diagonal march of sub-units onto the new alignment was involved. Deployment is a subject I will cover later on but it may also be possible to infer that because there would have been a time penalty as the column closed to masse, Austrian columns may have even formed in massen most of the time. These questions, however, will never be reconciled by reading the regulations and answers must be sought in contemporary accounts at the tactical level. The principal disadvantage of any mass of troops in obvious.

We know that the length to breadth ratio of massen was important and that they were formed as 'square' as possible. The zug column, however, was clearly not considered an appropriate formation from which to form massen, in which context I now have difficulty with the illustration at Figure 18 in my original article, which was taken from a reproduction of Plan 60 of the Exercier-Reglement 1807 in George Nafziger's article showing, my title notwithstanding, "Divisionmasse from Column of Züge".

[20] I will touch on this again later. I am bound to say, that the utility of a column consisting of 24 sub-units, one behind the other, would only seem appropriate during the approach march and not in a tactical environment.

In summary the masse was formed by battalion and regimental sized units as

'Masse' was merely a name given to what was a conventional closed column intended specifically to combine movement with firepower, the rear and front ranks providing musketry across the width of the formation, the flanking files providing it throughout the depth. It has gained notoriety as something unique. It was not and was identical in concept, for example, to the Prussian Angriffs-Colonne. [21]

Perhaps it would be apposite at this point to explain that 'breaking' had a particular meaning in the universal vocabulary of regulations at this time. It was also the basis of parallel deployment.

Breaking was simply the act of converting,

I include the first instruction because it is interesting in the context of the method used, as will be seen. This is described at Paragraph 1 to Section 3 "Brechung und Aufmarsch mit Reihen" ("Breaking and Deploying with Files").

[23]

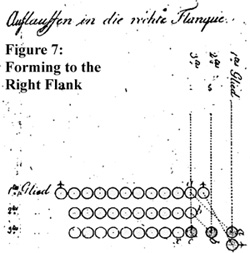

I admit to a degree of initial difficulty with the verb 'auflaufen' in this context'. Examination of the Abrichtungs-Reglement 1806, however, reveals that this is similar to what is known today as forming in the British army and simply another method of wheeling with a moving pivot where files march individually onto the new alignment. It is also similar to the French conversion, "a platoon marching in column of sections, changing direction on the flank of the marker". [24]

The command was,

This is a very complex manoeuvre, compared with a conventional wheel to a flank, as evidenced by the space devoted to it in its various forms, and one wonders if the average regiment was competent enough to use it. It is, nevertheless, documented in both the Exercier Reglement 1807 and Abrichtungs Reglement 1806 and was the only means by which divisions could change direction. [26]

This method of changing direction has been described as a conversion unique to the French Reglement 1791.

[27] Although not identical to the French, the concept is very similar, and was known to the Austrians at least as early as 1806.

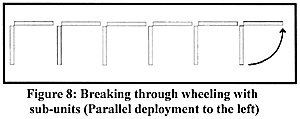

This is described at Paragraph 2 to Section 3 "Brechung durch die Schwenkung mit Abtheilungen" (Breaking through Wheeling with Sub-units). [28] The opening sentence notes that breaking "en colonne" was executed at the 'doublirschritt' by all sub-units wheeling simultaneously right or left on the spot with a stationary pivot. This is the means by which the classic parallel deployment was conducted everywhere. The largest sub-unit that could break by wheeling was the half-division. As noted the division's frontage was too great for wheeling, changes of front being performed by means of the auflaufen forming manoeuvre described above.

The opening sentence notes that breaking "en colonne" was executed at the 'doublirschritt' by all sub-units wheeling simultaneously right or left on the spot with a stationary pivot. This is the means by which the classic parallel deployment was conducted everywhere. The largest sub-unit that could break by wheeling was the half-division. As noted the division's frontage was too great for wheeling, changes of front being performed by means of the auflaufen forming manoeuvre described above.

The first cautionary command was

The word "schwenken!" (wheel) was the signal for the various NCOs and Officers to place themselves in the appropriate places to conduct the manoeuvre, which need not concern us here, except to say that it illustrates that converting from one formation to another was not an instantaneous procedure by any means, the time taken to deliver the order notwithstanding.

Once in place, a further cautionary command was given as follows

The executive command was "Marsch!"

Austrians clearly used practices that were essentially the same as everybody else's. An illustration of this method of deployment was shown at Figure 16 to my original article but I repeat it for the sake of completeness at Figure 8.

More As You Were

"The circumstances in which a line breaks in march and forms itself again must be determined in all cases and circumstances."

An illustration of the method from the section on the subject in the Abrichtungs Reglement 1806 is at Figure 6.

[18]

An illustration of the method from the section on the subject in the Abrichtungs Reglement 1806 is at Figure 6.

[18]

The Mass

"When one closes the sub-units of a column to rank-distance, a masse is produced."

a. A device to counter cavalry.

b. A device to facilitate deployment into line.

c. A device to facilitate manoeuvre.

d. A device to facilitate concealment.

Instructions for Breaking and Forming the Front

"into open column from line, maintaining distance on the march, and then wheeling back into line."

[22]

Breaking with Files

"Breaking with files to form either the line, or through 'auflaufen' to any direction where the first rank arrives on a position at will, is conducted by means of the elaborate explanation established in the Abrichtungs-Reglement, with the accompanying clear plans, so that further comment will be superfluous".

"Man wird in the die rechte oder linke Flanke auflaufen"! ("To the left or right flank form"!)

upon which the markers marched off onto the new alignment and halted. Files then marched onto the new alignment and fell in on them. An illustration from the Abrichtungs Reglement 1806 is at Figure 7. Changes of front to flank or rear could be accomplished using this method.

[25]

upon which the markers marched off onto the new alignment and halted. Files then marched onto the new alignment and fell in on them. An illustration from the Abrichtungs Reglement 1806 is at Figure 7. Changes of front to flank or rear could be accomplished using this method.

[25]

Breaking with Sub-units

"Man wird sich mit Zügen, halben-Compagnien, halben-Divisions recht oder links schwenken". ("By zügen, half-companies, half-divisions to the right or left wheel".).

"Mit Zügen, halben-Compagnien, halben-Divisions rechts oder links schwenkt euch" ("By Zügen, half-Companies, half-Divisions, right or left wheel dress!").

"Mit Zügen, halben-Compagnien, halben-Divisions rechts oder links schwenkt euch" ("By Zügen, half-Companies, half-Divisions, right or left wheel dress!").

Introduction and Battalion Organization

Column, Masse, and Breaking

Deploying

Tactial Examples, Footnotes

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #25

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com