I was thinking of giving this article the title: I'll Never Forget Arcola. In fact, I'll never forget my visits to all three battlefields in Northern Italy, but Arcola, or Arcole, will always remain something special. The reason for this will become clear in the section covering the battlefield site today. It was in fact the third site visit but since Arcola comes second in the order of battles historically, I'll leave Rivoli to the last.

I was thinking of giving this article the title: I'll Never Forget Arcola. In fact, I'll never forget my visits to all three battlefields in Northern Italy, but Arcola, or Arcole, will always remain something special. The reason for this will become clear in the section covering the battlefield site today. It was in fact the third site visit but since Arcola comes second in the order of battles historically, I'll leave Rivoli to the last.

Battle History

The Build up: From September to the 14th November

After the defeat of Wurmser at Castiglione in August, the Directory ordered Napoleon to advance through the Tyrol to join up with the French armies in Germany. He reported back that he couldn't do this due to the wretched state of his army at the time. Besides the Battle of Castiglione, they had suffered heavy losses in the numerous actions before it and were exhausted from the constant marching and fighting. Desperately needing to rest, reorganise and to be re-equipped. The Directory, however, required Napoleon to advance and thus draw Austrian troops, commanded by the able Archduke Charles, away from Germany.

The Austrians, however, with the same thought in mind, ordered Field Marshal Wurmser to make another attempt at relieving Mantua and so keep Napoleon busy in Italy. The result was a series of French victories at Roveredo, Caliano, Primolano, Bassano and the Battle of St. George. It also resulted in the Austrian Commander in Chief, with over 20,000 men, becoming trapped in the overcrowded fortress of Mantua. So ended the Austrian second counterattack, and only in Germany did they obtain any kind of success by forcing armies of Generals Moreau and Jourdan back to the Rhine.

Napoleon was now ordered to take up a defensive stance and to renew efforts to take Mantua, if not by force, then by starvation. The Directory promised him numerous reinforcements but less than 3,000 would finally arrive in November. This of course didn't even make up for the attrition that had occurred during the previous actions. To make matters worse, disease was now crippling his forces besieging Mantua and those in the marshy area of the lower Adige. The delay in sending reinforcements may have been due to the simmering resentment of some of the members of the Directory to Napoleon's growing popularity and successes. Additionally, the troops and officers eventually sent from the Vendée were poor in quality and had only experienced irregular combat.

Against them the Austrians were forming a new army, commanded by Feldmarschall Baron Josef Alvinci. (Sometimes spelt Alvinczy, Alvintzy, Alvintzi and even d'Alvintzi). Part of this army was positioned north of Lake Garda, commanded by General Paul Davidovitch.

Napoleon worked out that he would have a month's grace before the new Austrian commander could act. He decided to use the time to concentrate his forces ready for the coming offensive. When the Austrians attacked he hoped to use the same tactics that had worked so successfully in the Castiglione campaign.

Problems

However, there were a few problems. Firstly, there was the lack of reinforcements. Secondly, he couldn't lift the siege of Mantua this time to gain more troops. If he did so, the high numbers of Austrians contained in the fortress might march out and operate in his rear. Thirdly, he couldn't rely on a short warning of the Austrian advance and he needed early notice of their intentions.

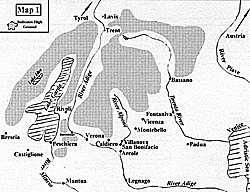

With this in mind he placed General Charles Henri Vaubois at Levis, north of Trent (Trento), with 10,500 men to keep a watch on Davidovitch. General André Massena, with 6,000 man, was sent to the east to Bassano to watch Alvinci, and General Pietre-Francois Augereau remained in Verona, with 6,000 men, as central reserve. General Barthelemy Joubert, with 4,000 men was to hold the Lower Adige area and to cover the forces besieging Mantua, while General Charles Kilmaine, with 8,000 men (including 500 locally enlisted troops) was placed in charge of the siege itself. Beaumont with about 2,500 cavalry was also positioned in reserve at Mantua.

General de Division Macquart (or Macquard) with around 3,000 men provided the garrisons at Brescia, Peschiera and Verona, and provided guards for parks and GHQ. Total French forces numbered around 39,000 men. Of these possibly as many as 10,000 were sick and wounded. (see Map 1 at right)

General de Division Macquart (or Macquard) with around 3,000 men provided the garrisons at Brescia, Peschiera and Verona, and provided guards for parks and GHQ. Total French forces numbered around 39,000 men. Of these possibly as many as 10,000 were sick and wounded. (see Map 1 at right)

Large Map 1 (slow download: 85K)

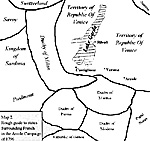

Besides wondering when and where the Austrians would attack, Napoleon had other worries. He was concerned that the Pope might persuade the thirty thousand strong Army of Naples to act against him. He was also concerned with the reaction of the surrounding states. (see Map 2 at left).

Besides wondering when and where the Austrians would attack, Napoleon had other worries. He was concerned that the Pope might persuade the thirty thousand strong Army of Naples to act against him. He was also concerned with the reaction of the surrounding states. (see Map 2 at left).

Large Map 2 (slow download: 47K)

At first they had welcomed the French as liberators but now they had become disillusioned by the heavy demands forced on them and collected by the Directory's agents. The bad behaviour of the French soldiers added to their misery.

However, on the 10th of October, Naples signed a peace treaty with France. Genoa became a French base and the only state that remained openly hostile was Modena. A state which had in fact re-supplied Mantua when the siege was lifted. Napoleon solved the problem by combining the states into new republics, such as the Cisalpine Republic, hoping eventually to unite these into the Kingdom of Lombardy.

As the days of October passed by fortunes appeared to improve for the French. There was still no sign of action by the Austrians. The weather, since winter was fast approaching, began to change for the worse, and this would hinder any Austrian movements in the Tyrol. Melting snows flowing down from the Alps would also make many rivers and streams impassable. Information from Mantua also indicated that conditions were bad, even though Wurmser had killed and salted all the cavalry horses. A wise move by the old campaigner but besides the army he also had a civilian population to feed and, due to sickness his fighting force was down to around 17,000 active troops. However, near the end of October, Napoleon learned that Alvinci had started concentrating his forces and that Davidovitch had also sent him troops; the latter appeared to be a possible false report which nearly ruined his plans. It did look though that the threatened Austrian attack was about to begin.

Even Numbers

Napoleon estimated that by the beginning of November, with reinforcements, he would have around 41,000 men with a further 3,000 locally enlisted troops, giving him a total of somewhere in the region of 44,000, including those besieging Mantua. Against him Alvinci, to the east, situated beyond the Piave River, had around 28,000 men. Davidovitch, situated north of Trent numbered somewhere in the region of 18,000. Combined, they slightly outnumbered Napoleon's troops, with a total of 46,000.

But Wurmser's 17,000 active troops trapped in Mantua were still a threat, and if added, gave the Austrians a new total of 63,000 men, far outnumbering the French forces. The Austrians advanced hoping the false information had wrong footed Napoleon, but both their movements were soon known to him.

Even so, Napoleon was sure that the Austrians wouldn't repeat the same mistake as Wurmser in the previous campaigns, and was probably surprised to learn that once again they had chosen to divide their forces. He decided to act quickly and go on the attack. He ordered Vaubois to attack Davidovitch and push him back towards Bolzano. He was sure that Davidovitch's command was now smaller than Vaubois' Division, because of the supposed troops sent to Alvinci. He wanted Vaubois to push Davidovitch out of the way and then send two brigades to join Massena at Bassano.

Massena meanwhile, was ordered to keep a watch on Alvinci's movements and to fall back to Vicenza if needed. Napoleon would advance to his aid with Augereau's Division and Beaumont's cavalry once Davidovitch had been dealt with. Kilmaine was left in charge of the troops in the Adige, Mincio and Mantua areas.

On the 2nd November, Alvinci crossed the Piave. One column, commanded by General Peter Quasdanovitch, with around 14,500 men, advanced towards Bassano, while another of similar size, commanded by General Johann Provera, headed for Fontaniva. Massena, obeying orders, fell back to Vicenza while Napoleon advanced to Montabello with Augereau's Division. When the Austrians began to cross the Brenta River, Napoleon immediately gave the order to attack their advance guards, who were well ahead of the main bodies.

The 6th November saw Massena holding Provera's advance guard, commanded by General Liptay, at Fontaniva, while Augereau held Quasdanovitch's advance guard, commanded by General Hohenzollern, at Bassano. Having both failed to push the Austrians back across the Brenta as Napoleon had planned, he ordered Massena and Augereau to withdraw as far as Vicenza. Napoleon was surprised by the tough fighting offered by the so called 'poorly trained' recruits. However, Alvinci was also upset by the actions and was actually considering a retreat! Napoleon then received news that Vaubois had been forced to fall back as far as Rivoli. He had wrongly estimated the numbers available to Davidovitch who had outfought and outmanoeuvred Vaubois.

Orders of maneuver

Augereau was quickly ordered to hold the Adige south of Verona while Massena was ordered to head for Verona itself. Colonel Vignoles was given the urgent job of collecting as many men as possible (he found the recently arrived battalion of the 40th Line Demi-Brigade at Verona) and to march them to Rivoli. General Joubert was ordered to advance to Rivoli with one of the brigades, possibly the 4th Light Demi-Brigade, besieging Mantua. They were all in place by the 8th and inspired by Napoleon's presence, wounded men, some still suffering and bleeding from their wounds, were said to have left the hospitals to rejoin the ranks. This in turn inspired the able-bodied French soldiers to greater efforts.

However, the 39th and 85th Demi-Brigades found inspiration in a different way. Napoleon belittled them for a lack of bravery in a searing speech that ended by saying that they no longer formed part of the Army of Italy. With a point to prove they earned their place back with some tough fighting in the days that followed.

For some reason Davidovitch failed to attack the French at Rivoli until the 15th. He may well have been waiting for Alvinci to arrive within supporting distance. Time wasting, beside splitting their forces, was another error the Austrians kept on making; costly mistakes which would eventually lead to their downfall. Vaubois, reinforced by the troops from Joubert and Vignole, now had around 12,000 men to stand against about 15-18,000 Austrians. Napoleon hoped these were enough for Vaubois to hold Davidovitch while he dealt with Alvinci.

Meanwhile, as Vaubois waited for Davidovitch to attack, Alvinci advanced to Verona but was pushed back to the village of Caldiero. Caldiero lay on mountain spur and was a strong position to defend, which Alvinci occupied with about 18,000 troops. His right was in the hills to the north and his left around the marshes with Arcola in the south. He had also left 3,500 troops at Bassano and sent 3,500, commanded by Colonel Brigido, as a diversion to Legnago. A further 3,000 more were placed to protect his lines of communication.

Napoleon went to Verona and placed Augereau with 6,000 men to hold the line along the Adige between Arcola and Legnago. (Jackson & Chandler appear to agree on this although Esposito & Elting place Augereau at Caldiero, with Massena attacking on his left. But this would surely leave Napoleon's right flank open to attack if the Austrians crossed the Alpone?) Massena, now reinforced to 13,000 by a brigade ordered up from Vaubois (a move which reduced the troops at Rivoli to less than 9,000 men) was placed in front of Verona. Macquart, with a small force of 2,500, garrisoned the city, while Kilmaine, with 8-9,000 troops, remained in charge of besieging Mantua.

On the 12th November, Napoleon gave the ordered Massena to attack Caldiero, but he was beaten back with heavy losses. The constant rain had helped the Austrian defenders, whose artillery was well positioned, by making it extremely difficult for the French to move theirs. Napoleon pulled his defeated troops back to Verona. Caldiero was his first and only defeat of the campaign and a reverse that threw Napoleon and his troops into despair. Even so, suggestions of withdrawing completely because they were massively outnumbered were brushed aside by Napoleon.

He made another 'no retreat... death or glory' speech, stating that they would have to fight and beat Alvinci to improve their position. Vaubois was therefore ordered to send yet another brigade, commanded by General Jean Guyeux (Guieu) and by the 14th, Napoleon had 19,000 men to face Alvinci, who he hoped he now outnumbered. However, Alvinci had also been busy collecting troops and had brought up a brigade from Bassano giving him 21,500 men, in addition to a further 3,500 on the Lower Adige.

Napoleon realised that to win he would have to force Alvinci to attack his troops in a good defensive position. One in which the Austrians couldn't deploy or rely on their superior numbers, and one that also favoured the attack of French columns supported by skirmishers. After inflicting severe casualties he then hoped to advance and defeat them decisively. As usual, it was all a matter of timing, timing that often went wrong, as it did in the Castiglione campaign. The area in front of Verona is a thin plain. To the north of it are some heights and to the south the River Adige. To the west Verona and to the east the Alpone, a tributary of the Adige. Between Caldiero and Bassano lay Villanova and San Bonifacio. South of Villanova, between the Adige and the Alpone, were the Arcola marshes and a few dike roads.

Napoleon's Plan

Napoleon's plan was to advance to the narrow defile at Villanova and so cut Alvinci's line of communication. He could then attack the Austrian supply parks and convoys and, by being in the their rear, force Alvinci to attack him in a good defensive position on the Adige.

To achieve this, surprise was vital. Napoleon could either cross the Adige at Albaredo or Ronco, both roads leading to Villanova. The easy route lay via Albaredo which would take him to the east bank of the Alpone, but surprise would be lost if his troops were seen too early by the Austrian cavalry patrols. Napoleon chose to cross at Ronco, hoping that the Austrians believed the marshes, made worse by three days of continual rain, were enough protection from French attacks and therefore less guarded than the Albaredo route. There was also the added advantage of a pontoon bridge site at Ronco which had been used in the earlier actions against Wurmser. Major Andreossy was given the job of constructing a bridge there as quickly as possible.

During the night of the 14th, Napoleon ordered Massena to march his division through Verona as if he were withdrawing to the Mincio River, but once clear of the Adige bridges he was to turn about and march along the west bank, uniting with Augereau's Division at Ronco. At dawn the bridge was ready and the French began to cross. The Battle of Arcola was about to begin.south of Villanova, between the Rivers Adige and Alpone, were the Arcola marshes and a few dike roads. Napoleon's plan was to advance to the narrow defile at Villanova and so cut Alvinci's line of communication. He could then attack the Austrian supply parks and convoys, and, by being in the their rear, would force Alvinci to attack him in a good defensive position.

More Arcola:

More in the Series

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #24

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com