This is the third and final article based on the early Napoleonic battles in Northern Italy during 1796/7 and my visits to three battlefield sites in 1994. I enjoyed my first holiday abroad and I’d go back to Italy again like a shot. I’ve also learned a lot about writing articles and my appreciation for others who have done likewise has grown enormously. It also proved an excellent way of making contacts with other like minded enthusiasts. This then, is number three, and covers the Battle of Rivoli in 1797 and the site today.

Battle History: The Build Up

From November 1796 to 14th January 1797

After his victory at Arcola in November 1796, Napoleon thought he would roughly have about another month before the Austrians would yet again send another army to relieve Mantua. In fact he had two months and Napoleon desperately vented to use them to prepare his army for the coming attack. However, Prance was becoming tired of war and the Directory, sensing this, wanted to offer the Austrians Mantua in exchange for Kehl, where General Jean Victor Marie Moreau, with 60,000 troops, was under siege by 40,000 Austrians. Napoleon of course, was totally against such a line of action but the Directory insisted and sent General Clarke to represent them and discuss terms. However, the talks came to a halt over Mantua when the French refused to allow the Austrians to send supplies to the besieged fortress. Not surprisingly, after their successes in Germany, the Austrians didn’t want to know anyway. They were convinced they would succeed in rescuing Feldmarschall (FM) Count Dagobert Sigismund Wurmser and his men on the next attempt. On top of this Napoleon had another problem. The Pope had broken the armistice during Feldmarschall Baron Josef Alvinci’s first advance and his troops posed a threat to the French from the south. The Pope’s plot with the Austrians was confirmed on the 7th of January, as explained explicitly in Angus Heriot’s book THE FRENCH IN ITALY, 1796-99, page 102:

“The Austrians’ foremost aim was still the relief of Mantua, to be followed by a junction with the Papal forces then arming: the latter project was supposed to be secret, but was disclosed to the French by the capture of an emissary who swallowed his despatches rolled up in a ball of sealing wax, hut was forced-literally-to disgorge them by the mulatto general Dumas, father of the famous writer.”

The captured despatch also revealed that the fourth attempt by the Austrians to relieve Mantua was about to begin. It appeared that their successes in Germany had not only given the Austrians a feeling of confidence but they had also inspired them to sort out the problem of Italy once and for all. A new army was raised comprising of 6,000 sharpshooters from the Tyrol, veteran troops transferred from Germany and new regiments formed. The Austrian Empress herself was said to have helped the growth of this confidence by personally embroidering the colours of the new regiments. The new Austrian army was said to have numbered somewhere in the region of 45,000 infantry and nearly 3,000 cavalry, not including another 10,000 troops capable of fighting trapped in Mantua. Meanwhile, during the lull, the French had been sent reinforcements of around 7,000 men, which pushed their total up to about 46,000 which included the 8,500 besieging Mantua and some troops protecting the French lines of communication.

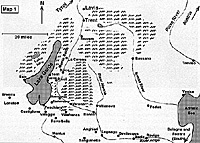

Napoleon had the same problem as in the Castiglione campaign. That of trying to discover where and when the Austrians would strike first. So, in order to cover all areas of attack, he placed his troops as follows:- (SEE MAP 1)

Napoleon had the same problem as in the Castiglione campaign. That of trying to discover where and when the Austrians would strike first. So, in order to cover all areas of attack, he placed his troops as follows:- (SEE MAP 1)

General Baron Louis Rey’s Division of about 4,150 troops to hold Salo, Lonato, Brescia, Peschiera and Valeggio, and so protecting the west and the approach to the Chiese valley. Field fortifications were built at La Corona where General B.C Joubert was sent with 10,300 men to block the Upper Adige valley. Some field fortifications were also built at Rivoli (Rivoli Veronese) where Joubert left some troops. General Andre Massena, with 1,800 men at Bussolengo and 7,500 east of Verona. General Pierre Francois Charles Augereau had 2,300 in Verona, 1,200 between Verona and Ronco, 1,500 at Legnago, 1,800 between Badia and Rovigo, a 1,200 screen at Bevilacqua, 1,500 in Reserve at Sanguinetto and 1,000 cavalry placed in various positions along the Adige. A further 2,800 troops (Possibly commanded by General Jean Lannes) supporting 4,000 local troops, was placed south at Bologna and Ferrara to keep a watch on the activities of the Papal forces. General Jean Mathieu Philibert Serurier was back in command besieging Mantua with 8,500 troops and Napoleon’s Headquarters was set at Roverbello.

Austrian Advance

While Napoleon was doing this the Austrians, once more under the command of Alvinci, now began to move against the French. Yet again the Austrians decided to split their forces. It was divided into two; one force attacking south while the other attacked from the east. Alvinci commanded the main body of troops attacking south, while General (or possibly General Major (GM)) Provera commanded those attacking from the east. Alvinci had 28,000 men (said to consist of 34 infantry battalions and 15 squadrons of cavalry) which he again split into six columns. One column, 5,000 men strong, commanded by General Lusignan, was to advance west of Monte Baldo to outflank Joubert at La Corona. Another, comprising 4,700 men under the command of General Liptay, was to launch a frontal attack west of the Adige at La Corona. General Koblos, commanding a third column of 4,000 men to do likewise. A fourth column of 3,400, commanded by GM Ocskay, to be in reserve behind Koblos and Liptay.

View north of Rivoli monument. Behind hill is Osteria Gorge

View north of Rivoli monument. Behind hill is Osteria Gorge

The fifth column was commanded by GM Prince Reuss under overall command of Feldmarschall Leutnant (FML) Peter Quasdanovich, who was to advance with 7,000 troops down the east bank of the Adige; cross to the west bank at Dolce, and then to attack Rivoli via the Osteria Gorge. (During my research I came across only one account that mentioned the Austrians having a pontoon train, and that was with Provera’s column to the east, and only one account that mentioned a bridge being thrown across the Adige at Dolce by Prince Reuss. Therefore, considering there are no other bridges or fords in the vicinity, we can assume that Quasdanovich did indeed command a pontoon train.)

The sixth column of 3,900 men, commanded by the Russian General Wukassovich, was to advance down the east bank of the Adige and attack Rivoli In the rear from the east. (Some accounts say his orders were to continue matching down the east bank and link up with Bajalich at Verona. However, if he was to attack Rivoli in the rear, which seems more likely since he would be supporting Quasdanovich, then he too must have had access to a pontoon train since again there are no indications of fords or bridges in the area where he finally set up his gun batteries. However, I came across no accounts of him trying to cross the Adige.) Other troops, the amounts and positions unknown, were probably placed to cover their lines of communication.

Only two roads were suitable for Alvinci’s artillery and supply wagons which were taken by Quasdanovich and Wukassovich’s columns. This meant that the other four columns had to travel across difficult terrain and could only take some light guns with them. Again, the amount of guns varies. Some accounts say they had no artillery while others say each column possessed at least one or two mountain guns carried on mules.

Alvinci’s plan however, was based on the fact that he wouldn’t move his men into action until four days after Provera had attacked from the east. Provera, like Alvinci, split his force into separate columns which began to move towards the French on the 8th of January.

One column of about 9,000 men, commanded by Provera himself, advanced towards Legnago, while the second smaller column of 5,000 troops, commanded by General Bajalich, advanced towards Verona. As with Alvinci, there were probably other troops positioned along their lines of communications. The aim of the two southern columns were to draw as many French troops as possible away from Alvinci’s main attack in the north; an attack that wouldn’t begin until the 12th.

Augereau’s troops were soon in action on the 8th at Bevilacqua and Massena reported Austrians in force advancing towards Villanova. Joubert and Rey meanwhile, reported all was quiet in the north. On the 10th, Austrians were seen at Badia and Augereau concentrated his troops around the bridge at Ronco. Even with these reports Napoleon still wasn’t sure where the main Austrian attack would strike, although it seemed probable that it would come from across the Venetian plain.

Slow Advance

The Austrians were slow in advancing. This was due not only to the rough and mountainous terrain but also the winter weather which made the tough going that much harder. Their enforced slowness might have also been the reason why, that even on the 11th, Napoleon still couldn’t figure out Alvinci’s plan of attack.

The fog of war would soon begin to lift however, when, on the 12th, Massena’s troops were in action at Verona against Bajalich, and on the 13th Joubert sent word he was under attack at La Corona. Even with correct information collected by his spies, Napoleon was still unsure at this stage of where the main Austrian assault would come from, although it appeared to be from the east in the Lower Adige area; which was exactly what Alvinci vented him to think. Had the weather conditions been better the Austrians may well have been able to exploit the situation.

Napoleon, although still uncertain of where the main attack was coming from, gave orders for Massena to move to the west bank of the Adige and to be ready to move north or south whatever the need may be. Part of his division was to remain to protect Verona, but it still left him with three brigades (about 7,000 men) to move wherever ordered. Rey was to concentrate 4,500 men at Castelnuovo. Augereau was to remain at Ronco while Lannes was ordered to the Badia area leaving only the Italian troops to vetch for any movements south from the Pope’s forces. Cannes objective was to stop any Austrians from breaking through to connect up with the Papal forces.

Late in the afternoon on the 13th, Napoleon was just about to attack Bajalich, when he received news that Joubert had been outnumbered and outflanked and forced back to Rivoli. Napoleon now realised where the main attack was coming from. Immediately he headed for Rivoli and sent word to Serurier to be on his guard in case the Austrians should try to sortie out from Mantua.

He ordered Augereau to send some cavalry and artillery to Rivoli. Massena was to move to Rivoli with three brigades and to form up between the east bank of Lake Garda and Joubert’s left flank. The same command was given to Rey although Napoleon knew he couldn’t reach Rivoli until the 14th. (Some accounts state that General Claude Victor-Perrin was also ordered to Villafranca with detachments from Serurier and Augereau, numbering possibly 2,500 men.) General (& Aide-de-camp) Joachim Murat was given a special order by Napoleon.

At Salo he commanded a small brigade of infantry, cavalry and two guns and was watching for any signs of Austrian activity along the western side of Lake Garda. If there were none he was to send his cavalry off to join the main army. After midnight, he was to take his infantry (one battalion being the carabiniers of the 11th Demi-Brigade) two guns and some pioneers, and was to cross the lake during the night using the boats collected by the French earlier. He was to land somewhere in the region of Torri on the eastern shore, and then march into a position that would threaten the Austrian rear. If unable to do this he was to try and join Joubert. To aid him, gunboats from Peschiera would create confusion by making diversionary attacks along the shore.

The French forces were estimated to number about 17,000 early on the 14th of January, which consisted of Joubert’s Division and most of Massena’s. During the day, with the arrival of Rey’s troops, it would rise to 23,000 men. This force included about 1,500 cavalry and at least 30-40 guns. A further 6,000 men were at Badia with Lannes, 7,000 with Augereau covering the Lower Adige and 3,000 from Massena’s Division between Bussolengo and Verona. Opposing Napoleon’s 17,000 early on the 14th Alvinci could deploy 28,000 troops, giving him an advantage of over 10,000 men. He also had the 14,000 troops commanded by Provera in the Lower Adige, and Wurmser could possibly sortie out with about 10,000 fit men.

Odds

Overall this gave the Austrians a total of around 52,000 troops against 39,000 French. But, like all great battle plans, gaining a victory relied heavily on good timing and luck, something the Austrians were to be sadly lacking as time went by. Also against them was the fact that, this time, the situation was reversed to that of Castiglione and Arcola. At Rivoli the Austrians would be attacking the French who, even though outnumbered, now held a strong defensive position and with their artillery well placed.

As planned, on the 11th, Koblos began his frontal attack on La Corona, but Liptay, (because Lusignan’s column had been held up by snow and other natural obstacles and had not appeared on the French left), did not move his column into attack. The other three columns, including artillery and cavalry had also been ordered not to move until La Corona had been taken. Due to this Joubert was able to deal with the individual attacks as they came, and it wasn’t until late on the 12th that he was forced to retreat when the Austrians finally managed to outflank him. Lusignan’s column appearing on the left and Quasdanovich’s column on the right.

Early on the 13th he moved back to Rivoli. The Austrians followed but there was little action. The Austrian troops probably badly needed to rest after their exhausting march and food supplies for the columns were already becoming a problem. However, during the night, Joubert saw the Austrian camp fires belonging to the various columns, and, realising he wouldn’t be able to hold the position against such odds, decided to withdraw to Bussolengo. Rivoli was now only held by a rearguard. Unknown to the Austrians another opportunity to exploit passed them by.

Part Two: The Battle of Rivoli

More in the Series

Back to Table of Contents -- First Empire #25

Back to First Empire List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1995 by First Empire.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com