Preparations

With but five days between MacArthur's radiogram and D Day there was little time to make ready. But in accordance with GHQ's earlier orders, planning had begun in January when Krueger directed the 1st Cavalry Division to prepare terrain, logistical, and intelligence studies. Krueger, Whitehead, and Barbey had begun a series of planning conferences on 19 February.

Kinkaid's and Barbey's plans, issued on 26 February, provided for transporting and landing the reconnaissance force, then reinforcing it or withdrawing it if necessary. With the cruisers Nashville and Phoenix and four destroyers Rear Adm. Russell S. Berkey was to provide cover during the approach to the Admiralties and to deliver supporting gunfire against Los Negros, Lorengau, and Seeadler Harbour during the landings. The attack group, which Barbey placed under command of Rear Adm. William M. Fechteler, his deputy, consisted of eight destroyers and three APD 'S. (Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 435-36; Rad, Comdr Seventh Flt to CTF's 76 and 74, and CTG 74-2, 26 Feb 44, in GHQ SWPA G-3 Jnl, 28 Feb 44.)

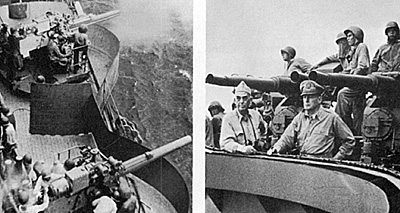

ABOARD THE CRUISER PHOENIX, 28 February 1944. Left, gunfire directed at

Japanese heavy guns; right, Admiral Kinkaid and General MacArthur viewing the

bombardment.

ABOARD THE CRUISER PHOENIX, 28 February 1944. Left, gunfire directed at

Japanese heavy guns; right, Admiral Kinkaid and General MacArthur viewing the

bombardment.

The cruisers were added to the force because General MacArthur elected to accompany the expedition, and to invite Admiral Kinkaid to go with him, to judge from firsthand observation whether to evacuate or hold after the reconnaissance. The first plans had called for just one destroyer division and three APD's, but when Kinkaid learned of MacArthur's decision he added two cruisers and four destroyers. This was necessary because a destroyer had neither accommodations nor communications equipment suitable for a man of MacArthur's age and rank. A cruiser would serve better, but a single cruiser could not go to the Admiralties. Kinkaid's policy forbade sending only one ship of any type on a tactical mission. Therefore he sent two cruisers, and the two cruisers required four additional destroyers as escorts. (Oral statement of Adm. Kinkaid to the author et al., 16 Nov 53.)

The air plans prescribed the usual missions but necessarily compressed them into a few days. Bad weather limited the air effort on 26 February, but next day four B-25 squadrons attacked Momote and Lorengau while seven squadrons of B-24's attacked the Wewak fields and B-25's struck at Hansa Bay. Heavy attacks against the Admiralties and Hansa Bay followed on 28 February, and that night seven B-24's attacked Hollandia, far to the west. (Craven and Cate, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, P. 563.)

Krueger had originally planned to send a preinvasion reconnaissance party to the western tip of Manus, from where it was to patrol eastward for several weeks and radio reports to his headquarters. But the new orders caused him to cancel this plan in favor of a reconnaissance on Los Negros. More data on Hyane Harbour and Japanese dispositions there and at Mornote would have been useful, for there was still no agreement on enemy strength in that region. Willoughby's estimate of 4,050 conflicted sharply with that offered by Whitehead, who stated on 26 February that there were not more than 300 Japanese, mostly line of communications troops, on Los Negros and Manus. (Rad, Comdr AdVon Fifth AF to Comdr AAF, 26 Feb 44, in GHQ SWPA G-3 Jnl, 26 Feb 44.)

And the 1st Cavalry Division's estimate placed Japanese strength at 4,900, despite an assertion in its field order that "Recent air reconnaissance . . . results in no enemy action and no signs of enemy occupation." (Cf par. 1a (2) of BREWER TF FO 2, 25 Feb 44, with Annex I, Int, in ALAMO ANCHORAGE jnl 3, 24-6 Feb 44. The reconnaissance forces estimated 1,500 on Los Negros, altogether 4,350 in the Admiralties. ALAMO FO 9 and BREWER TF FO 1 are orders prepared for the one-division invasion of the Admiralties scheduled for 1 April.)

Because Krueger did not wish to risk betraying Allied plans by sending a patrol to Hyane Harbour and Momote, he decided to send one to examine the region about one mile south of the harbor. Accordingly, at 0645, 27 Februaryp a PBY delivered a six-man party of ALAMO Scouts to a point five hundred yards off Los Negros' southeast shore under cover of air bombardment. The scouts took a rubber boat ashore, found a large bivouac area on southeastern Los Negros, and reported by radio that the area between the coast and Momote was "lousy with Japs." But when this report reached GHQ Kenney discounted it. He pointed out, with reason, that twenty-five enemy "in the woods at night" might give that impression and that the patrol had examined not the airdrome but only a part of the south end of Los Negros. (Kenney, General Kenney Reports, P- 361)

This patrol did provide more data on which to base plans for naval gunfire support. Kinkaid and Barbey decided that one cruiser and two destroyers should fire on the bivouac area while the other cruiser and two more destroyers fired at Lorengau and Seeadler Harbour and other destroyers supported the landing itself.

The 1st Cavalry Division, which was to provide the landing force, was unique in the U.S. Army in World War II. Dismounted and serving as infantry, it was a square division of two brigades plus division artillery. Each brigade consisted of two cavalry regiments of about two thousand men each. Each regiment was composed of headquarters, service, and weapons troops, and two squadrons. The squadrons contained a headquarters troop, three rifle troops, and a weapons troop. The weapons troop, using the organization of the infantry heavy weapons company, had been added in 1943. (The 1st Cavalry Division, a Regular Army unit with a high percentage of Regular officers and enlisted men, was not organized until 1921, but its regiments had long and distinguished histories. The 5th Cavalry (originally the 2d Cavalry), organized in 1855, was commanded by Robert E. Lee, and the 7th Cavalry was George A. Custer's old regiment.)

Division artillery had a headquarters battery, two 75-mm- pack howitzer battalions, and two 105-mm. howitzer battalions.

MacArthur's orders of 24 February specified that the landing force should number eight hundred men, including five hundred men of one squadron with additional artillery and service troops, but the next day he recommended that a slightly stronger force be used. (Rad, MacArthur to Comdr ALAMO, CC, AdVon Fifth AF, and Comdr VII Amphib Force, 25 Feb 44, in GHQ SWPA G-3 Jnl, 25 Feb 44.)

On 26 February Krueger established the occupation force for the Admiralties as the BREWER Task Force. He placed it under Maj. Gen. Innis P. Swift, commanding the 1st Cavalry Division, and assigned to it the ground force units previously allotted by GHQ.

For the D-Day landing Krueger and Swift organized the BREWER reconnaissance force under Brig. Gen. William C. Chase, commander of the 1st Cavalry Brigade. It consisted of detachments from 1st Cavalry Brigade Headquarters and Headquarters Troop; the 2d Squadron, 5th Cavalry; two 75-mm. howitzers of B Battery, 99th Field Artillery Battalion; the 673d Antiaircraft Artillery Battery (.50-caliber machine guns); the 1st Platoon, B Troop, ist Medical Squadron; the 30th Portable Surgical Hospital; air and naval liaison officers and a shore fire control party; and a detachment of the Australian New Guinea Administrative Unit-- or about a thousand men.

If the landing succeeded and the reconnaissance force stayed, the BREWER support force, under Col. Hugh T. Hoffman, was to land on D Plus 2. Hoffman's command embraced the remainder of the 5th Cavalry and the 99th Field Artillery Battalion, in addition to C Battery (90-mm.), 168th Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion; A Battery (multiple .50caliber mount), 21 ith Antiaircraft Artillery Battalion; medical, engineer, and signal units from the 1st Cavalry Division; and E Company, Shore Battalion, 592d Engineer Boat and Shore Regiment. The 40th Naval Construction Battalion and detachments from other elements of the 4th Construction Brigade, all from the South Pacific, were to accompany the Support Force.

The remainder of the BREWER Task Force, including the rest of the 1st Cavalry Brigade and the 2d Cavalry Brigade, was to follow if needed as soon as shipping became available. To shorten sailing time, Cape Cretin was to be used as a staging area for reinforcements.

Hyane Harbour, scene of the initial landing, was indeed an unlikely place. Two small points of land about 750 yards apart flanked the entrance; from them the enemy could put cross fire against landing craft sailing through the narrow gap in the barrier reef. Much of the shore line inside the harbor was covered by mangroves, but on the south, 150 yards behind Momote airfield, a 1,200-yard sandy beach with three jetties offered passage to troops and vehicles. (Map 20)

With H Hour set for 0815 to give bombers time to deliver heavy strikes in support of the landing, the APD's were to anchor five thousand yards off Hyane Harbour. The destroyers carrying troops would enter the transport area to unload their passengers, then return to their fire support stations. Twelve LCP(R)'s were to carry the reconnaissance force ashore. The first three waves of four craft each would go in at five-minute intervals, unload, return forty minutes later, and depart again in three waves five minutes apart until the troops were ashore.

To join the expedition, MacArthur and Kinkaid flew to Milne Bay and boarded the cruiser Phoenix in the afternoon of 2 7 February. The same afternoon at Oro Bay, where the ist Cavalry Division had been unloading ships and receiving amphibious training, the BREWER reconnaissance force boarded Admiral Fechteler's ships, 170 men per APD and about 57 men per destroyer. The ships departed Oro Bay in late afternoon and early evening of 28 February, rendezvoused with Berkey's cruisers and destroyers early next morning just south of Cape Cretin, and followed eleven miles behind Berkey through Vitiaz Strait and the Bismarck Sea. No enemy ship or plane made an appearance. The sea was calm, the sky heavily overcast, as the ships neared Hyane Harbour.

The Landings

Fechteler ordered his ships to deploy at 0723, 29 February. Cruisers and destroyers took their support stations and commenced firing at 0740. APD's in the transport area lowered landing craft which proceeded toward their line of departure 3,700 yards from the beach.

The heavy overcast and generally bad flying weather prevented all but a handful of Allied B-24's from reaching the Admiralties before H Hour. P-38 S, B-25's, and smoke-laying reconnaissance planes arrived later, but before they could attack the overcast closed in so tightly that they could do nothing. "The Fifth Air Force had made its chief contribution in pointing out the opportunity." (Craven and Cate, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, P. 564.)

FIRST WAVE OF LANDING CRAFT UNLOADING men of G Troop, 2d Squadron, 5th

Cavalry, 29 February 1944.

FIRST WAVE OF LANDING CRAFT UNLOADING men of G Troop, 2d Squadron, 5th

Cavalry, 29 February 1944.

The first sign of the Japanese came at H minus 20 minutes when the first wave of landing craft reached the line of departure. As it passed through the entrance, enemy 20-mm. machine guns on either side opened fire while heavier guns directed their fire against the Phoenix and the destroyers. The cruiser and the destroyer Mahan promptly silenced a gun on Southeast Point, and other vessels silenced the machine guns. According to Admiral Kinkaid this performance so thoroughly converted General MacArthur into a naval gunfire enthusiast that he became more royalist than the king, and thereafter Kinkaid frequently had to point out the limitations of naval gunfire to the general. (Oral statement of Adm Kinkaid to the author et al., 16 Nov 53.)

Support plans called for naval gunfire to stop at 0755 (H minus 20 minutes) so that B-25's could bomb and strafe at low altitudes, but at 0755 no B-25's could be seen nor could any be reached by radio. The ships fired, therefore, until 0810, and then fired star shells as a signal that strafers could attack in safety. Soon afterward three B-25's bombed the gun positions at the entrance to the harbor. ( Craven and Cate, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, p. 564.)

Thus supported by air and naval bombardment, the leading wave of landing craft, carrying G Troop, 2d Squadron 5th Cavalry, met little fire as it passed through the entrance and turned left (south) toward the beach. It touched down at 0817, whereupon an enemy machine gun crew on the beach scrambled back for cover. The first man ashore, 2d Lt. Marvin J. Henshaw, led his platoon across the narrow beach to take a semicircular position on the edge of a coconut plantation. There were no American casualties, but several Japanese were killed as they hastily made off in the direction of the airstrip.

The Japanese resumed their positions at the harbor entrance when the naval shelling ceased and fired at the LCP(R)'s as they returned to the APD's. The Mahan steamed to within a mile of shore and fired 2o-mm. and 40- mm- guns at the southern point. She could not put fire on the point opposite because the LCP(R)'s were in the way. As the second wave started through the entrance so much enemy fire came from the skidway and from the northern point that it turned back. The destroyers Flusser and Drayton then put their fire on the north point while the Mahan pounded the southern. When the enemy fire ceased, the landing craft reformed, went through the passage, fired their machine guns at the skidway, and landed 150 men of the second wave at H plus 8 minutes.

The second wave then passed through the first about a hundred yards inland. The third wave, which with the fourth received enemy fire on the way in, landed at H plus 30 minutes, pushed southwest, and established a line just short of the airstrip that included most of the eastern revetment area. So far, except for firing at the boats, the Japanese had not fought. At 0900 General Chase radioed Krueger that a line had been established three hundred yards inland, and "enemy situation undetermined." (Serial 7, 0900, 1st Cav Brigade Unit jnl, 29 Feb 44, VOL III of 1st Cav Brigade Hist Rpt Admiralty Islands Campaign.)

By 0950 the squadron, commanded by Lt. Col. William E. Lobit, had overrun Momote airfield. The troopers found it covered with weeds, littered with rusty fuselages, and pitted with water-filled bomb craters.

While the beachhead was relatively peaceful, the landing craft continued to receive fire on the way in and out. The destroyers continued intermittent bombardment of the harbor entrance for about six hours. By the time the LCP(R)'s of the third wave had returned to the APD's, four of the total twelve had been damaged by the enemy gunfire. Because the landing force probably could not be evacuated without the LCP(R)'s (although emergency plans called for an APD to penetrate the harbor and evacuate the 2d Squadron), the landing craft abandoned their schedule and entered the harbor only when the destroyers had forced the enemy to cease fire. A heavy rainstorm, which prevented the few Allied planes over the target from bombing, soon reduced visibility so much that the Japanese fire became ineffective.

The entire reconnaissance force was unloaded by 1250 (H Plus 4 hours, 35 minutes). Caliber .50 antiaircraft guns and the two 75-mm pack howitzers had been manhandled ashore. Two cavalrymen had been killed, three wounded. Five Japanese were reported slain. Two sailors of the landing craft crews were dead, three wounded.

"Remain Here"

By afternoon Lobit's squadron had advanced over the entire airfield including the western dispersal area, an advance of thirteen hundred yards on the longest axis, without encountering any more Japanese. Patrols moved across the island to Porlaka and north to the skidway without seeing an enemy. But it was clear that the Japanese had not evacuated. Other patrols advancing to the south had found signs of recent occupancy, such as three kitchens and a warehouse full of rations, and a captured document indicated that some two hundred antiaircraft artillerymen were camped nearby.

2D LT. MARVIN J. HENSHAW receiving the congratulations of General MacArthur, who awarded him the Distinguished Service Cross, 29 February 1944.

2D LT. MARVIN J. HENSHAW receiving the congratulations of General MacArthur, who awarded him the Distinguished Service Cross, 29 February 1944.

General MacArthur and Admiral Kinkaid came ashore about 1600. MacArthur awarded the Distinguished Service Cross to Lieutenant Henshaw, inspected the lines, received reports, and made his decision. He directed General Chase "to remain here and hold the airstrip at any Cost." ( Quoted in 1st Cav Brigade Hist Rpt Admiralty Islands Campaign, I, 3. There are other versions of MacArthur's statement in existence.)

Having "ignored sniper fire . . . wet, cold, and dirty with mud up to the ears," he and Kinkaid returned to the Phoenix, whence MacArthur radioed orders to send more troops, equipment, and supplies to the Admiralties at the earliest possible moment. ( Comment by Lt Col Julio Chiaramonte, attached to Ltr, Gen Chase to Gen Smith, Chief of Mil Hist, 6 Nov 53, no sub, OCMH; Rad, CINCSWPA to CTF 76, and CG's ALAMO and Fifth AF, 29 Feb 44, in GHQ SWPA G-3 Jnl, 1 Mar 44.)

The cruisers and most of the destroyers departed for New Guinea at 1729, leaving behind the destroyers Bush and Stockton to support the cavalrymen.

Chase and Lobit had obviously concluded that the larger estimate of enemy strength, rather than the airmen's, was the right one. If all the Japanese they estimated to be on Los Negros should counterattack, the one thousand men of the reconnaissance force would find it very difficult to hold both the airfield and the dispersal area.

An inland defense line, about three thousand yards long exclusive of the shore, would have been required to defend them. Because such a line could not safely be held by one thousand men, Chase decided to pull back east of the airstrip. He set up a line about fifteen hundred yards long which ran from the beach southward for about nine hundred yards, then swung sharply east to the sea. The troops did not occupy Jamand1lai Point in their rear, but blocked its base that night and cleared it the next morning. The position selected on the edge of the strip provided a ready-made field of fire to the west.

In late afternoon the troopers organized their defenses. The beachhead was too small to permit the 75-mm. pack howitzers to cover the area immediately in front of the lines. Consequently the field artillerymen were turned into riflemen. The .50-caliber antiaircraft guns were set up on the front line. Outposts were established in the dispersal area on the other side of the airstrip.

DIGGING A FOXHOLE THROUGH CORAL ROCK near the airstrip, 29 February 1944.

DIGGING A FOXHOLE THROUGH CORAL ROCK near the airstrip, 29 February 1944.

The soldiers found digging foxholes even more arduous than usual, for the soil was full of coral rock. The Americans' defenses suffered from two weaknesses: the impossibility of field artillery support immediately in front of the line, and the lack of barbed wire.

To remedy the latter, Chase urgently requested Krueger to arrange for an airdrop of barbed wire and stakes, as well as mortar and small arms ammunition, on the north end of Momote drome as soon as possible. (Item 25, 1st Cav Brigade Unit Jul, 29 Feb 44.)

Careful preparations for defense were more than justified, because except for the air force ground crews the Japanese had not been evacuating either Los Negros or the island group. The larger intelligence estimates had been correct. And the Japanese, warned by American submarines that sent "frequently lengthy operational messages" from south of the Admiralties in late February, had been on the alert for an attack. (Southeast Area Naval Operations, III, Japanese Monogr No. 50 (OCMH), 66.)

Most of the Admiralty garrison was stationed on Los Negros, with the 1st Battalion, 229th Infantry responsible for the defense of the airfield and Hyane Harbour. One battalion defended Lorengau. The Japanese, expecting attack through Seeadler Harbour, had let the Americans slip in through the back door, but now they planned to take action. When General Imamura found out about the invasion, he ordered Colonel Ezaki to attack with his entire strength. (8th Area Army Operations, Japanese Monogr No.110 (OCMH), p. 135.)

Ezaki did not immediately use the 2d Battalion, 1st Independent Mixed Regiment, but left it at Salami Plantation north of the skidway. He directed the rst Battalion, 229th, commanded by a Captain Baba, to attack that night and "annihilate the enemy who have landed. This is not a delaying action. Be resolute to sacrifice your life for the Emperor and commit suicide in case capture is imminent." (This order, a copy of which was captured, is quoted in part in [Frierson] The Admiralties, p.33.)

As dusk fell Japanese riflemen and the American outposts began a fire fight, whereupon the outposts were recalled. Shortly afterward small groups of enemy began moving up against the 2d Squadron's line in a series of un-co-ordinated attacks. Relying chiefly on grenades, the enemy groups attacked in darkness. Some managed to infiltrate through the line and cut nearly all the telephone wires.

Baba's battalion delivered its heaviest attack against the southern part of the perimeter. Some Japanese, using life preservers, swam in behind the American lines and landed. Another group broke through along the shore at the point of contact of the left (east) flank of E Troop and the right (south) flank of the field artillery unit, which was holding the beach. The Americans defended by staying in their foxholes and firing at every visible target and at everything that moved.

Two Japanese soldiers moved through the darkness and penetrated to the vicinity of General Chase's command post. Before they could do any damage Maj. Julio Chiaramonte, force S-2, killed one and wounded the other with a submachine gun.

By daylight of 1 March most of the enemy attackers had withdrawn. During the morning the infiltrators who had hidden themselves were hunted down and killed. Seven Americans were dead, fifteen wounded, as compared with sixtysix enemy corpses within the perimeter.

So far the reconnaissance force had held its own. But because the support force would not arrive until the next day patrols pushed westward and northward to determine just what Japanese opposition was to be expected. After moving an average distance of four hundred yards they encountered the enemy in some strength. Clearly, another attack was probable.

Chase's situation was improved during 1 March by the arrival of more ammunition. As the weather had cleared, three B-25's dropped supplies at 0830. Later in the day a B-17 of the 39th Troop Carrier Squadron made two supply runs, and four B-17's of the 375th Troop Carrier Group each dropped three tons of blood plasma, ammunition, mines, and grenades. The reconnaissance force received no barbed wire. (Craven and Cate, The Pacific: Guadalcanal to Saipan, P. 565, state that barbed wire was dropped but several days later Chase was still protesting that he had not received any.)

Captured documents had indicated the location of many enemy defensive positions, and the patrols that went out in the morning brought back more data. By now the Americans knew that Los Negros' south coast possessed prepared positions, and that the western dispersal area, Porlaka, and the coast of Hyane Harbour from the 2d Squadron's perimeter north to the skidway were fortified. In consequence the two supporting destroyers and the 75-mm. pack howitzers bombarded these areas. Starting at 1600 Fifth Air Force planes bombed the dispersal area, and at 1715, when antiaircraft guns near the south end of the airstrip fired on the planes, the Bush and Stockton pulled to within a thousand yards of the shore and shelled them.

Several 4th Air Army fighter planes from Wewak appeared but failed in their effort to drive off the American planes. The air bombardment flushed a body of Japanese, estimated one hundred strong, from cover in the dispersal area. When these men rushed east across the strip in an effort to escape the bombs, most were cut down by the cavalrymen's fire.

Otherwise enemy ground forces remained quiescent during most of the afternoon except for a seventeen-man patrol of officers and sergeants, led by Captain Baba, which had apparently infiltrated the lines on the previous night. Baba's patrol came through heavy underbrush to within thirty-five yards of General Chase's command post. When the Americans sighted the patrol, Chase and his executive officer, Col. Earl F. Thompson, directed the movements of Major Chiaramonte and four enlisted men who moved out to the attack. After Chiaramonte's party had killed several Japanese, the others committed suicide with grenades and swords.

The Japanese varied their pattern by striking at the perimeter at 1700 instead of after dark in an attack that was weaker than the one of the night before. Daylight simplified the defenders' task in repelling the attack, which ceased at 2000. Thereafter throughout the night small groups harried and infiltrated the lines. About fifty Japanese used life belts to cross the harbor entrance and attack the position at the base of Jamandilai. In the course of the action the field artillerymen fired three hundred 75-mm rounds at the enemy and also killed 47 Japanese within the artillery positions with small arms fire. All together, 147 Japanese were killed within the perimeter during the two night battles.

Actually, the Japanese, though possessing numerical superiority, had never used their full strength and had not seriously threatened Chase's force, which still held its lines intact on the morning of 2 March. Recklessness, coupled with the skill and tenacity of the cavalrymen, had cost the Japanese their best chance.

More Action in the Admiralties

- The Decision

The Reconnaissance in Force

To the Shores of Seeadler Harbour

Lorengau

The Advance East

Jumbo Map: Lugos Mission to Lorengau (very slow: 182K)

Jumbo Map: Los Negros Assault (very slow: 247K)

Jumbo Map: Seeadler Harbor Area (very slow: 262K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Operation Cartwheel

Back to World War Two: US Army List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com