Supporting Operations

In invading Empress Augusta Bay, Halsey's forces were bypassing formidable enemy positions in southern Bougainville and the Shortlands, and placing themselves within close range of all the other Bougainville bases, as well as within fighter range of Rabaul-thus the strong air attacks by the Fifth Air Force and the Air Command, Solonions. In addition, Halsey had planned to make sure that the Japanese bases on Bougainville were in no condition to launch air attacks during the main landings on 1 November. (This subsection is based on Halsey and Bryan, Admiral Halsey's Story, pp. 177-79; Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 292-93; Admiral Frederick C. Sherman, Combat Command: The American Aircraft Carriers in the Pacific War (New York: E. P. Dutton & Co., Inc., 1950), pp. 199-200; ONI USN, The Bougainville Landing and the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay, pp. 25-37)

Forces assigned to this mission were the 2 carriers, 2 antiaircraft light cruisers, and 10 destroyers of Admiral Sherman's Task Force 38 and the 4 light cruisers and 8 destroyers of Admiral Merrill's Task Force 39.

Task Force 38 sortied from Espiritu Santo on 29 October, Task Force 39 from Purvis Bay on Florida Island on 31 October. Both were bound initially for Buka.

Merrill, sailing well south of the Russells and west of the Treasuries on his 537-mile voyage in pursuance of Halsey's tight schedule, got there first. He arrived off Buka Passage at 0021, 1 November, and fired 300 6-inch and 2,400 5-inch shells at Buka and Bonis fields. Shore batteries replied but without effect.

Merrill then retired at thirty knots toward the Shortland Islands. Enemy planes harassed the task force but the only damage they did was to the admiral's typewriter. One fire started by the bombardment was visible from sixty miles away.

About four hours after the beginning of Merrill's bombardment Task Force 38 reached a launching position some sixty-five miles southeast of Buka. This was the first time since the outbreak of the war in the Pacific that an Allied aircraft carrier had ventured within fighter range of Rabaul, and the first tactical employment of an Allied carrier in the South Pacific since the desperate battles of the Guadalcanal Campaign. In Admiral Sherman's words:

"We on the carriers had begun to think we would never get any action. All the previous assignments had gone to the shore-based air. Admiral Halsey had told me that he had to hold us for use against the Japanese fleet in case it came down from Truk..." (Sherman, Combat Command, p. 200.).

The weather was bad for carrier operations as the planes detailed for the first strike, a force made up of eighteen fighters, fifteen dive bombers, and eleven torpedo bombers, prepared to take off in the darkness. The sea was glassy and calm; occasional rain squalls fell. There was no breeze blowing over the flight decks, and the planes had to be catapulted into the air, a slow process that, coupled with the planes' difficulties in forming up in the dark, delayed their arrival over Buka until daylight. Two torpedo bombers and one dive bomber hit the water upon take-off, doubtless because of the calm air. The rest of the planes dropped three 1,000-pound bombs on Buka's runway and seventy-two 100-pound bombs on supply dumps and dispersal areas.

The next strike--fourteen fighters, twenty-one dive bombers, and eleven torpedo bombers-- was launched at 0930 without casualties. These planes struck Buka again and bombed several small ships offshore. At dawn the next morning, 2 November, forty-four planes attacked Bonis, and at 1036 forty-one more repeated the attack. Then Sherman, under orders from Halsey, headed for the vicinity of Rennell, due south of Guadalcanal, to refuel. In two days of action Task Force 38, operating within sixty-five miles of Buka, estimated that it had destroyed about thirty Japanese planes and hit several small ships. More important, it had guaranteed that the Buka and Bonis runways could not be used for air attacks against Admiral

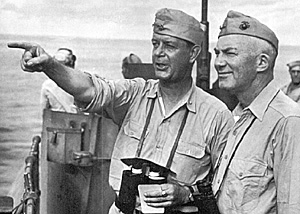

MAJ. GEN. ALLEN H. TURNAGE (right) and Commodore Laurence F. Reifsnider

aboard a transport before the landings on Bougainville.

Wilkinson's ships. The Americans lost seven

men and eleven planes in combat and

operational crashes.

MAJ. GEN. ALLEN H. TURNAGE (right) and Commodore Laurence F. Reifsnider

aboard a transport before the landings on Bougainville.

Wilkinson's ships. The Americans lost seven

men and eleven planes in combat and

operational crashes.

Meanwhile Merrill's ships had sped from Buka to the Shortlands in the early morning hours of I November to bombard Poporang, Ballale, Faisi, and smaller islands. Merrill had bombarded these before, on the night of 29-30 June, but in stormy darkness. Now the bombardment was in broad daylight; it started at 0631, seventeen minutes after sunrise. Japanese shore batteries replied with inaccurate fire. Only the destroyer Dyson was hit, and its casualties and damage were minor. His mission completed, Merrill headed south.

Approach to the Target

The last days of October found Wilkinson's ships busy loading and rehearsing at Guadalcanal and the New Hebrides .(The rest of this chapter is based on Morison, Breaking the Bismarcks Barrier, pp. 296- 305; Rentz, Bougainville and the Northern Solomons, pp. 21-39; ONI USN, The Bougainville Landing and the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay, PP. 37-49; SOPAC- BACOM, The Bougainville Campaign, Ch. III, OCMH; 8th Area Army Operations, Japanese Monogr No. 110 (OCMH), pp. 103-05; Southeast Area Naval Operations, III, Japanese Monogr No. 50 (OCMH), 11-13; Outline of Southeast Area Naval Air Operations, Pt. IV, Japanese Monogr No. 108 (OCMH), P. 46; observations of the author, who participated as a member of D Battery, 3d Marine Defense Battalion.)

Wilkinson had organized his eight transport and four cargo ships of Task Force 31's northern force into three transport divisions of four ships each. A reinforced regiment of marines was to be carried in each of two of the divisions, the reinforced 3d Marine Defense Battalion in the third. The four transports of Division A, carrying 6,421 men of the 3d Marines, reinforced, departed Espiritu Santo on 29 October and steamed for Koli Point on Guadalcanal. There Admiral Wilkinson and General Vandegrift boarded the George Clymer. General Turnage, 3d Marine Division commander, and Commodore Laurence F. Reifsnider, the transport group commander, had come up from the New Hebrides rehearsal in the Hunter Liggett.

Transport Division B, after the rehearsal, took the 6,103 men of the reinforced 9th Marines from the New Hebrides and in the late afternoon Of 30 October joined with the four cargo ships of Transport Division C south of San Cristobal. Division C carried the reinforced 3d Marine Defense Battalion, 1,400 men, and a good deal of heavy equipment.

All transport divisions, plus 11 destroyers, 4 destroyer-minesweepers, 4 small minesweepers, 7 minelayers, and 2 tugs, rendezvoused in the Solomon Sea west of Guadalcanal at 0740, 31 October. They sailed northwestward until 1800, then feinted toward the Shortlands, and after dark changed course again toward the northwest. During the night run to Empress Augusta Bay PB4Y4's (Navy Liberators), PV-i's (Vega Ventura night fighters), and PBY's (Black Cats) covered the ships. Enemy planes were out that night and made contact with the covering planes but apparently did not spot the ships, for none was attacked and Japanese higher headquarters received no warnings.

Empress Augusta Bay was imperfectly charted and the presence of several uncharted shoals was rightly suspected. Consequently Wilkinson delayed arrival at the transport area until daylight so that masthead navigation could be used to avoid the shoals.

The Landings

At 0432 of 1 November, Wilkinson's ships changed course from northwest to northeast and approached Cape Torokina in Empress Augusta Bay. Speed was reduced from fifteen to twelve knots. The minesweepers went out ahead to check the area. General quarters sounded on all ships at 0500, and forty-five minutes later the ships reached the transport area. The transport Crescent City struck a reef but suffered no damage.

Sunrise did not come until 0614, but the morning was bright and clear enough for the warships to begin a slow, deliberate bombardment of Cape Torokina at 0547. As each transport passed the cape it too fired with its 3-inch and antiaircraft guns. Wilkinson set H Hour for the landing at 0730. At 0645 the eight transports anchored in a line pointing north-northwest about three thousand yard from shore; the cargo ships formed a similar line about five hundred yards to seaward of the transports.

Wilkinson, sure that the Japanese would launch heavy air attacks, had come so lightly loaded that four to five hours of unloading time would find his ships emptied. Vandegrift and Turnage, anticipating little opposition at the beach, had planned to speed unloading by sending more than seven thousand men ashore in the assault wave. They would land along beaches (eleven on the mainland and one on Puruata Island off Cape Torokina) with a total length of eight thousand yards.

The assault wave boarded landing craft at the ships' rails. The winchmen quickly lowered the craft into the water; and the first wave formed rapidly and started for shore.

The scene was one to be remembered, with torpedo bombers roaring overhead, trim gray destroyers firing at the beaches, the two lines of transports and cargo ships swinging on their anchors, and the landing craft full of marines churning toward the enemy. This scene was laid against a natural backdrop of awesome beauty. The early morning tropical sun shone in a bright blue sky.

MOUNT BAGANA

MOUNT BAGANA

A moderately heavy sea was running, so that at the shore a white line showed where the surf pounded on the black and gray beaches, which were fringed for most of their length by the forbidding green of the jungle. Behind were the rugged hills, and Mount Bagana, towering skyward, emitting perpetual clouds of smoke and steam, dominated the entire scene.

The destroyers continued firing until 0731, when thirty-one torpedo bombers from New Georgia bombed and strafed the shore line for five minutes. The first troops reached the beach at 0726, and in the next few minutes all the assault wave came ashore. There was no opposition except at Puruata Island and at Cape Torokina and its immediate vicinity. There the Japanese, though few in numbers, fought with skill and ferocity.

Cape Torokina was held by 270 Japanese soldiers of the 2d Company, 1st Battalion, and of the Regimental Gun Company, 23d Infantry. One platoon held Puruata. On Cape Torokina the enemy had built about eighteen log- andsandbag pillboxes, each with two machine guns, mutually supporting, camouflaged, and arranged in depth. He had also emplaced a 75- mm. gun in an openended log-and-sand bunker to fire on landing craft nearing the beach.

Neither air bombardment nor naval gunfire had had any appreciable effect on these positions. Because air reconnaissance had shown that the enemy had built defense positions on Cape Torokina (a low, flat, sandy area covered with palm trees), it had been a target for naval bombardment. Two destroyers had fired at the cape from the south, but had done no damage. Exploding shells and bombs sent up smoke and dust that made observation difficult; some shells had burst prematurely in the palm trees. Poor gunnery was also a factor, for many shells were seen to hit the water. (See Rentz, Bougainville and the Northern Solomons, P. 34; Isely and Crowl, The U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, p. 180.)

Thus when landing craft bearing the 3d Marines neared the cape the 75-mm. gun and the machine guns opened fire. The men were forced to disembark under fire and to start fighting the moment they put foot to the ground. Casualties were lighter than might have been expected--78 men were killed and 104 wounded in the day's action-but only after fierce fighting and much valor were the men of the 3d Marines able to establish themselves ashore. The pillboxes were reduced by three- man fire teams: one BAR man and two riflemen with M1s, all three using grenades whenever possible. The gun position was taken by Sgt. Robert A. Owens of A Company, 3d Marines, who rushed the position under cover of fire from four riflemen. He killed part of the Japanese crew and drove off the rest before he died of wounds received in his assau lt. (Sergeant Owens received the Medal of Honor posthumously.)

By 1100 Cape Torokina was cleared. Most of its defenders were dead; the survivors retreated inland. Puruata Island was secured at about the same time, although some Japanese remained alive until the next day. Elsewhere the landing waves, though not opposed by the enemy, pushed inland slowly through dense jungle and a knee-deep swamp that ran two miles inland and backed most of the beach north and east of Cape Torokina. The swamp's existence had not previously been suspected.

Air Attacks and Unloading

The Allied air forces of the South and Southwest Pacific Areas had performed mightily in their effort to neutralize the Japanese air bases at Rabaul, Bougainville, and the Shortlands, but they had not been able to neutralize Rabaul completely. In planning the invasion of Empress Augusta Bay, the South Pacific commanders were aware that the Japanese would probably counterattack from the air. General Twining had arranged for thirty-two New Georgia-based fighter planes of all types then in use in the South Pacific--Army Air Forces P-38's, New Zealand P-40's, and Marine F4U's--to be overhead in the vicinity all day. These planes were vectored by a fighter director team aboard the destroyer Conway. Turning in an outstanding performance, they destroyed or drove off most of the planes that the Japanese sent against Wilkinson. But they could not keep them all away.

At 0718, as the last boats of the assault wave were leaving their transports, the destroyers' radars picked up a flight of approaching enemy planes then fifty miles distant. The covering fighters kept most of the planes away, but a few, perhaps twelve, dive bombers broke through to attack the ships.

These bombers had come from Rabaul, where the enemy commanders were making haste to organize counterattacks. On 30 October Vice Adm. Sentaro Omori, commanding a heavy cruiser division, had brought a convoy into Simpson Harbor at Rabaul. Next morning a search plane reported an Allied convoy of three cruisers, ten destroyers, and thirty transports near Gatukai in the New Georgia group. This was probably Merrill's task force; it could not have been Wilkinson's.

On receiving this report Admiral Kusaka ordered the planes of his 11th Air Fleet to start attacks, and he and Koga, over the protests of the 8th Fleet commander, who warned of the dangers of sending surface ships south of New Britain, directed Omori to take his force and all the 8th Fleet ships out to attack. This Omori did, but he missed Merrill and returned to Rabaul on the morning of 1 November.

Then came the news of the landing at Empress Augusta Bay. General Hyakutake was still sure that the main Allied attack would be delivered against southern Bougainville, but General Imamura ordered him to destroy the forces that had landed. Imamura. also arranged with Kusaka for a counterattacking force from the 17th Division, made up of the 2d Battalion, 54th Infantry, and the 6th Company, 2d Battalion, 53d Infantry, to be transported to Empress Augusta Bay. (This force had been standing by awaiting orders to move to western New Britain. It was separate from the 17th Division units scheduled for Bougainville mentioned above, P. 238.)

It would be carried on 6 destroyer- transports and escorted by 2 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, and 6 destroyers, all under Omori.

Admirals Koga and Kusaka, just completing their preparations for Operation RO, also ordered out their planes. The weather had come to their assistance by halting the heavy raid General Kenney had planned for 1 November. Koga alerted the 12th Air Fleet for transfer from Japan to Rabaul. Kusaka sent out planes of his 11th Air Fleet. The carrier planes apparently did not take part on 1 November.

According to enemy accounts, Japanese planes delivered three separate attacks against Wilkinson on I November. The Japanese used a total of 16 dive bombers and 104 fighters, of which 19 were lost and 10 were damaged. (Southeast Area Naval Operations, III, Japanese Monogr NO. 50 (OCMH), p. 46; p. 13 states that twenty-two planes were lost.)

When Wilkinson's ships received warning at 0718, the transports and cargo ships weighed anchor and steamed for the open sea. They escaped harm, and the dive bombers were able to inflict only light damage to the destroyers. Two sailors were killed. The transports returned and resumed unloading at 0930, having lost two hours.

Another enemy attack at 1248 succeeded in breaking through the fighter cover. Warned again by radar, the transports, with the exception of the American Legion, which stuck on an uncharted shoal, fled. The Japanese attacked the moving ships instead of the Legion. No damage was done, but the ships lost two more hours of unloading time. (As usual the Japanese claims, like those of American pilots, were exaggerated. They said they sank two transports and a cruiser.)

The halts in unloading caused by air attacks, coupled with beach and terrain conditions that Admiral Halsey described as "worse than any we had previously encountered," slowed the movement of supplies and equipment. (Halsey and Bryan, Admiral Halsey's Story, p.179.)

Fully one third of the landing force--5,700 men in all-had been assigned to the shore party, but nature and the Japanese aircraft thwarted efforts to unload all the ships on D Day.

Surf's Up

Even on quiet days the surf at Empress Augusta Bay was rough, and on 1 November a stiff breeze whipped it higher. The northernmost beaches were steep and narrow.

LCVP's ON THE BEACH AT EMPRESS AUGUSTA BAY damaged by the rough, driving

surf.

LCVP's ON THE BEACH AT EMPRESS AUGUSTA BAY damaged by the rough, driving

surf.

The surf, and possibly the inexperience of some of the crews, took a heavy toll of landing craft. No less than sixty-four LCVP's and twenty-two LCM's broached on shore and were swamped by the driving surf. As surf conditions got worse, several beaches became completely unusable. Five ships were shifted to beaches farther South, with more delay and congestion at the southern beaches. It was during this move that the American Legion ran aground.

By 1730 the eight transports were empty and Wilkinson took them back to Guadalcanal. But the four cargo ships, which carried heavy guns and equipment, were still practically full. Vandegrift, who had had ample experience at Guadalcanal in being left stranded on a hostile shore while much of his equipment remained in the holds of departing ships, persuaded Wilkinson to allow the cargo ships to put out to sea for the night and return the next morning to unload. (Miller, Guadalcanal: The First Offensive, pp. 79-81.)

Most of the troops aboard went ashore in LCVP's before Commodore Reifsnider led the cargo ships out to sea. D Battery of the 3d Defense Battalion, for example, its 90-mm. antiaircraft guns, fire control equipment, and radars deep in the holds of the Alchiba, which had lost all its LCM's in the raging surf, went ashore as infantry and occupied a support position in the sector of the 9th Marines.

Except for the full holds of the cargo ships, D Day had been thoroughly successful. All the landing force, including General Turnage, Brig. Gen. Alfred H. Noble, corps deputy commander, Col. Gerald C. Thomas, the corps chief of staff, and several other officers, were ashore. General Vandegrift returned to Guadalcanal on the George Clymer, leaving Turnage in command at Cape Torokina. By the day's end the division held a shallow beachhead from Torokina northward for about four thousand yards.

Aside from unloading the cargo ships (a task that was expeditiously accomplished the next day), the main missions facing the amphibious and ground commanders and the troops were threefold: to bring in reinforcements; to organize a perimeter defense capable of beating off the inevitable Japanese counterattack; and to build the airfields that would put South Pacific fighter planes over Rabaul.

More Invasion of Bougainville

- Decision To Bypass Rabaul

The General Plan

Air Operations in October

Forces and Tactical Plans

Preliminary Landings

Seizure of Empress Augusta Bay

Jumbo Map 15: Bougainville (monstrously slow: 794K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Operation Cartwheel

Back to World War Two: US Army List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com