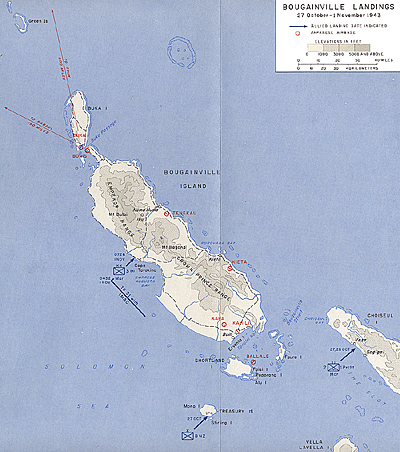

Jumbo Map: Bougainville (monstrously slow: 794K)

While MacArthur's and Halsey's troops were gaining the Trobriands, the Markham Valley, the Huon Peninsula, and the New Georgia group for the Allied cause, the joint Chiefs of Staff and their subordinate committees in Washington had been making a series of decisions affecting the course of the war in the Pacific. These decisions related not so much to CARTWHEEL itself as to General MacArthur's desire to make the main effort in the Pacific along the north coast of New Guinea into the Philippines. But, since they called for troops to support the offensives in Admiral Nimitz' Central Pacific Area, they had an immediate impact upon CARTWHEEL, especially on the Bougainville invasion (Operation B of ELKTON III) and on MacArthur's plans to seize Rabaul and Kavieng after CARTWHEEL.

The Decision To Bypass Rabaul

Once the Combined Chiefs at Casablanca had approved an advance through the Central Pacific, the joint Chiefs put their subordinates to work preparing a general strategic plan for the defeat of Japan. An outline plan was submitted at the meeting of the Combined Chiefs in Washington, 12-15 May 1943. The Combined Chiefs approved the plan as a basis for further study. (Cline, Washington Command Post, pp. 219-22.)

The plan, which governed in a general way the operations of Nimitz' and MacArthur's forces until the end of the war, aimed at securing the unconditional surrender of Japan by air and naval blockade of the Japanese homeland, by air bombardment, and, if necessary, by invasion.

The American leaders agreed that naval control of the western Pacific might bring about surrender without invasion, and even without air bombardment. But if air bombardment, invasion, or both proved necessary, air and naval bases in the western Pacific would be required. Therefore, the United States forces were to fight their way westward across the Pacific along two axes of advance: a main effort through the Central Pacific and a subsidiary effort through the South and Southwest Pacific Areas (See Map 1.) (in point of fact the terms "main effort" and "subsidiary effort," though used constantly, bore so little relation to the number of troops, aircraft, and ships engaged as to be almost without meaning.

In general, the Central Pacific had the preponderance of fleet (included carrier-based air) strength; MacArthur had the greater number of divisions and land-based aircraft.)

The Washington commanders and planners preferred the Central Pacific route for the main effort because it was shorter and more healthful than the South-Southwest Pacific route; it would require fewer ships, troops, and supplies; success would cut off Japan from her overseas empire; destruction of the Japanese fleet, which would probably come out fighting to oppose the advance, would enable naval forces to strike directly at Japan; and it would outflank and cut off the Japanese in the Southeast Area.

The main effort should not be made through the South and Southwest Pacific Areas, it was argued, because a drive from New Guinea to the Philippines would be a frontal assault against large islands with positions closely arranged in depth for mutual support. The Central Pacific route, in contrast, permitted the continuously expanding U.S. Pacific Fleet to strike at small, vulnerable positions too widely separated for mutual, support.

The Joint Chiefs decided on the two axes, rather than the Central Pacific alone, because the Japanese conquests in the first phase of the war had compelled the establishment of comparatively large Allied forces in the South and Southwest Pacific Areas; to shift all these to the Central Pacific would take too much time and too many ships, and would probably intensify the already strong and almost open disagreement between MacArthur and King over Pacific strategy. Further, the joint Chiefs hoped to use the oilfields on the Vogelkop Peninsula. (This hope came to nothing. Robert Ross Smith, The Approach to the Philippines, UNITED STATES ARMY IN WORLD WAR II (Washington, 1953), PP. 425-28.)

Twin drives, co-ordinated and timed for mutual support, would give the U.S. forces great strategic advantages, for the Japanese would never know where the next blow would fall. (See JSSC 40/2, 3 Apr 43; JPS 67/4, 28 Apr 43; JCS 287, 7 May 43; JCS 287/1, 8 May 43; CCS 220, 14 May 43. All these papers are entitled "Strategic Plan for Defeat of Japan" or something very similar. See also Crowl and Love, The Seizure of the Gilberts and Marshalls, Ch. I; Smith, The Approach to the Philippines, Ch. 1; Cline, Washington Command Post, Ch. XVII; relevant chapters in Morton's forthcoming volumes on strategy, command, and logistics in the Pacific, and in Maurice Matloff, Strategic Planning for Coalition Warfare: 1943-1944, also in preparation for the series UNITED STATES ARMY IN WORLD WAR II.)

At Washington in May the Combined Chiefs, as they had at Casablanca, approved plans for seizure of the Gilbert and Marshall Islands as the opening phase of the Central Pacific advance. They also approved the existing plans for CARTWHEEL, which the joint Chiefs estimated would be ended by April 1944.

Next month, the joint Chiefs, concerned with the problem of co-ordinating Nimitz' and MacArthur's operations, asked MacArthur for specific information on organization of forces and dates for future operations and informed him that they were planning to start the Central Pacific drive in mid-November. They planned to use the 1st and 2d Marine Divisions, then in the Southwest and South Pacific Areas, respectively, all the South Pacific's assault transports and cargo ships (APA's and AKA's), and the major portion of naval forces from Halsey's area. (Min, JCS mtg, 15 Jun 43; Rad, JCS to MacArthur, 15 Jun 43, CM-OUT 6093.)

Faced with the possibility of a rival offensive, using divisions and ships that he had planned to employ, General MacArthur hurled back a vigorous reply. Arguing against the Central Pacific (he called the prospective invasion of the Marshalls a "diversionary attack"), he set forth the virtues of advancing through New Guinea to the Philippines. Withdrawal of the two Marine divisions, he maintained, would prevent the ultimate assault against Rabaul. He concluded his message with the information on target dates and forces that the Joint Chiefs had requested. (Rad, MacArthur to Marshall, 20 Jun 43, CM-IN 13149.)

Two days later, 22 June, Admiral Halsey protested the proposed removal of the 2d Marine Division and most of his ships. (Rad, MacArthur to Marshall, 22 Jun 43, CM-IN 13605. Halsey sent his views to MacArthur who relayed them.)

Although General MacArthur may not have known it at the time, his argument that transfer of the two divisions would jeopardize the Rabaul invasion was being vitiated. In 1942 there had been general agreement that Rabaul should be captured, but in June 1943 members of Washington planning committees held that a considerable economy of force would result if Rabaul was neutralized rather than captured. (Incl B, Jt War Plans COm 58/1), 24 Jun 43, title: Memo for RAINBOW Team, in OPD 384 Marshall Islands (10 Jun 43) Sec 1.)

The Joint Strategic Survey Committee, in expressing itself in favor of giving the Central Pacific offensive priority over CARTWHEEL, also argued that the Allied drive northward against Rabaul was merely a reversal of the Japanese strategy of the year before and held "small promise of reasonable success in the near future." (JSSC 386, 28 Jun 43, title: Strategy of the Pac.)

On the other hand Admiral William D. Leahy, chief of staff to the President and senior member of the joint Chiefs, was always a strong supporter of MacArthur's views. (See Fleet Admiral William D. Leahy, I Was There (New York: Whittlesey House, 1950), passim.)

He argued strongly against any curtailment of CARTWHEEL. Admiral King, however, was far from pleased (in June 1943) with the rate of "Inch by inch" progress in the South and Southwest Pacific. He wanted to see Rabaul "cleaned up" so the Allies could "shoot for Luzon," and seemed to imply that if CARTWHEEL did not move faster he would favor a curtailment. (Min, JCS mtg, 29 Jun 43. At this time King wanted to go to Luzon by way of the Marianas, which he always regarded as the key to the Pacific because he believed that an attack there would smoke out the Japanese fleet.)

The immediate question on the transfer of the Marine divisions was compromised. The 1st Marine Division would remain in the Southwest Pacific. The 2d Marine Division, heretofore slated for the invasion of Rabaul, was transferred from New Zealand to the Central Pacific, where it made its bloody valorous assault on Tarawa in November 1943. Assured by King that the Central Pacific offensive would assist rather than curtail CARTWHEEL, Leahy withdrew his objections. (Min, JCS Mtg, 20 Jul 43; JCS 386/1, 19 Jul 43, Strategy in the Pac; JPS 205/3, 10 Jul 43, title: Opns Against Marshall Islands; Draft Memo, JPS for JCS, 12 Jul 43, sub: Strategy in the Pac, OPD 381 Security 195; OPD Draft Memo, 14 Jul 43, no sub, same file; JPS draft paper, 19 Jul 43, title: Strategy in the Pac, and attached papers, with JPS 2ig/D in ABC 384 Pac (28 Jun 43); OPD Brief, Notes on JWPC 58/2, in OPD 384 Marshall Islands (to Jun 43) Sec 1).

By 21 July the arguments against capturing Rabaul had so impressed General Marshall that he radioed MacArthur to suggest that CARTWHEEL be followed by the seizure of Kavieng on New Ireland and Manus in the Admiralties, with the purpose of isolating Rabaul, and by the capture of Wewak. But MacArthur saw it otherwise. Marshall's plan, he stated, involved too many hazards. Wewak, too strong for direct assault, should be isolated by seizing a base farther west. Rabaul would have to be captured rather than just neutralized, he insisted, because its strategic location and excellent harbor made it an ideal naval base with which to support an advance westward along New Guinea's north coast. (Rad 8604, Marshall to MacArthur, 21 Jul 43, in Marshall's OUT Log; Rad 16419, MacArthur to Marshall, 23 Jul 43, in Marshall's IN Log.)

Marshall and King were not convinced. Thus the Combined Chiefs, meeting with President Roosevelt and Prime Minister Churchill in Quebec during August, received and approved the joint Chiefs' recommendation that Rabaul be neutralized, not captured. They further agreed that after CARTWHEEL MacArthur and Halsey should neutralize New Guinea as far west as Wewak, and should capture Manus and Kavieng to use as naval bases for supporting additional advances westward. Once these operations were concluded, MacArthur was to move west along the north coast of New Guinea to the Vogelkop Peninsula.

Subsequently, MacArthur was informed that his cherished ambition to return to the Philippines would be realized; Marshall radioed him that once the Vogelkop was reached, the Southwest Pacific's next logical objective would be Mindanao. (See Cline, Washington Command Post, P. 225; CCS 319/5, 24 Aug 43, title: Final Rpt to the President and Prime Minister; CCS 301/3, 27 Aug 43, title: Specific Opns in Pac and Far East, 194344; Rad 8679, Marshal to MacArthur, 2 Oct 43, in Marshall's OUT Log. See also Smith, The Approach to the Philippines, Ch. I.)

Papers containing the Combined Chiefs decisions were delivered to General MacArthur by Col. William L. Ritchie of the Operations Division, War Department General Staff, who reached GHQ on 17 September. (Rad, Ritchie to Handy, 18 Sep 43, CM-IN 13521.)

From then on MacArthur did not raise the question of Rabaul with the joint Chiefs; his radiograms dealt instead with broader questions relating to the Philippines and the relative importance of the Central and Southwest Pacific offensives. (MacArthur's subsequent plans called for the neutralization of Rabaul, followed by its possible capture. See GHQ SWPA, RENO III, 20 Oct 43, in ABC 384 Pac, Sec 3-A.)

Although the evidence is not conclusive, the general course of events and certain opinions MacArthur gave during the planning for Bougainville seem to indicate that he knew of the decision to neutralize rather than capture Rabaul, or else had reached the same decision independently, some time before Colonel Ritchie reached the Southwest Pacific.

More Invasion of Bougainville

- Decision To Bypass Rabaul

The General Plan

Air Operations in October

Forces and Tactical Plans

Preliminary Landings

Seizure of Empress Augusta Bay

Jumbo Map 15: Bougainville (monstrously slow: 794K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Operation Cartwheel

Back to World War Two: US Army List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2002 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com