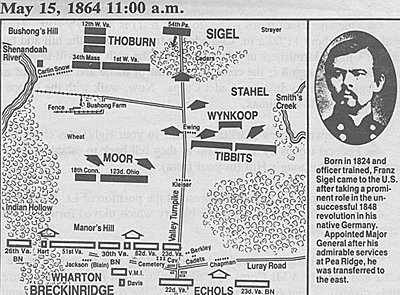

Breckinridge decided to advance to good defensive positions south of New Market and to entice Sigel to attack him. Accordingly, he had his column moving at 0100 on the rainy morning of 15 May, the VMI cadets joining the column at 0130 after spending a gloomy night in the Mt. Tabor Church. The advance began to encounter Federal cavalry vedettes after going about six miles. These caused some delay but, more importantly, alerted Colonel Moor. Moor had his men standing to arms by 0300 and earlier had sent back word to Edinburg for the 18th Connecticut to advance. That unit began a speed march so hastily about 0300 that it left Companies F and H on picket. These were drawn in at daylight and began a forced march without rest or food, running the last two miles. They arrived just in time to go into the battle at the moment of Breckinridge's attack.

Breckinridge decided to advance to good defensive positions south of New Market and to entice Sigel to attack him. Accordingly, he had his column moving at 0100 on the rainy morning of 15 May, the VMI cadets joining the column at 0130 after spending a gloomy night in the Mt. Tabor Church. The advance began to encounter Federal cavalry vedettes after going about six miles. These caused some delay but, more importantly, alerted Colonel Moor. Moor had his men standing to arms by 0300 and earlier had sent back word to Edinburg for the 18th Connecticut to advance. That unit began a speed march so hastily about 0300 that it left Companies F and H on picket. These were drawn in at daylight and began a forced march without rest or food, running the last two miles. They arrived just in time to go into the battle at the moment of Breckinridge's attack.

By about 0600 Breckinridge's force had closed to a position just south of the county boundary (the Fairfax line). He held them there in a heavy rain for about two hours while he reconnoitered Colonel Moor's position. Then, after sunrise, he had the 18th Virginia Cavalry probe Moor's line, hoping this would precipitate a Federal attack on his prepared positions. Disappointed in this, he placed his artillery on Shirley's Hill to continue to harass the Federals and to develop the situation. By then, Colonel Moor had established his line firmly along the old River Road and around the Lutheran church. It continued to be anchored on the west by a section of Ewing's West Virginia horse gunners.

East of them the line was filled by the exhausted 18th Connecticut, then the 123d Ohio, and the 1st West Virginia. Snow's Maryland Battery remained in the Lutheran cemetery, and the 34th Massachusetts briefly remained east of the Pike. Additional help was still far to the north. Brigadier General Jeremiah Sullivan left Woodstock at 0500 with the 12th West Virginia, the 54th Pennsylvania, and three batteries (von Kleiser's, Carlin's, and DuPont's). The 28th Ohio and 116th Ohio left Woodstock later at 0800 with the trains, at the same time that Sigel and his staff departed. Sigel could hear gunfire by the time he reached Edinburg, but when he caught up with Sullivan's force at Mt. Jackson he lingered for nearly an hour before continuing farther south.

Meanwhile, Breckinridge's and Moor's artillery continued to engage each other. Part of Snow's Battery had moved forward briefly until persuaded of the superiority of the Confederate positions on Shirley's Hill. Major General Julius Stahel, Sigel's cavalry chief, arrived on the scene about 0830 and, while assuming command, took exception to Moor's deployment. Perhaps he was alert to the need to close the gap between Sigel's components. His efforts, however, produced confusion and a growing sense among the troops that they were not being led well. A measure of this confusion may be seen in the experience of the 34th Massachusetts: The regiment was about to breakfast in its position east of the Lutheran church when it was ordered back to the Bushong House. Shortly after arriving, it was marched back to its starting position and ordered to send skirmishers out. No sooner was this accomplished than the unit was pulled back to an assembly area north of the present 54th Pennsylvania monument. Then it was moved westward into its final position on Bushong Hill, having marched about seven miles back and forth for no apparent purpose.

Battle Joined

By 1000 it was evident to Breckinridge that the Federals had no intention of attacking him. Consequently, he decided to be the aggressor: "I shall advance on him. We can attack and whip them here, and I'll do it." He ordered his lines forward to Shirley's Hill and maneuvered them around to create the impression of greater strength. Finally, he aligned them so as to appear to be three strong battle lines, when in reality he had one line staggered in three echelons. Wharton's Brigade was in two lines:

On the westernmost side was the 51st Virginia, then the 30th Virginia Battalion and Smith's 62d Virginia. To the right rear of this line was a smaller line composed of the 26th Virginia Battalion and the VMI cadets. Echo is' Brigade was drawn up farther east by the Pike and south of the village. His 22d Virginia linked with the troops west of the Pike while the 23d Virginia Battalion extended east until it connected with Imboden's cavalry, which screened the area up to Smith's Creek.

After another hour of bombardment, Breckinridge's force began to move forward. The 30th Virginia preceded Wharton's Brigade as it dashed over the crest of Shirley's Hill and down into the New Market Valley. It was followed in the same informal manner by the veteran 51st and 62d Virginia. But no one had told the inexperienced cadets to proceed in open order. Consequently, they marched down the hill with the 26th Battalion in drill-field formation, providing an excellent target to the fully alerted Federal gunners and sustaining their first five casualties. Echols' Brigade pressed forward on the east, conforming to Wharton's movement.

The Federal line was set up as described earlier, except that von Kleiser's New York Battery later was to come up to a support position on the Pike a quarter-mile north of the Lutheran church. The 18th Connecticut had dashed up into the line about 1100, just as Breckinridge's skirmishers came over the hill. A drenching rain was falling, and the guns continued to duel. Hardtack was issued to the newly arrived troops, but the men could not finish it because of adjustments being made to their line. Companies A and B and, later, Company D of the 18th Connecticut were sent forward from the River Road to the southern brow of the hill to act as skirmishers. While they were doing this, about 1140 Breckinridge withdrew his guns off Shirley's Hill and sent them to a position just south of the village. The cadet gun section joined them there. Only Jackson's Battery remained on the hill to support Wharton's advance directly. While this was going on, about 1145 Sigel and Sullivan reached Rude's Hill. Sigel paused briefly to watch the battle, then galloped forward with his retinue. Sullivan remained with his brigade just south of Rude's Hill, awaiting orders.

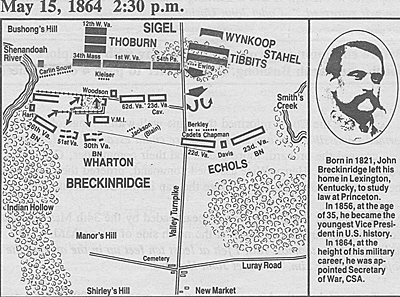

The Confederate advance resumed about noon. Breckinridge had adjusted his line somewhat by bringing the 26th Virginia up to the west of the 51st Virginia and sending it down Indian Hollow, a small valley on the west running toward the Shenandoah. This left the VMI cadets as his only reserve. On the other flank, Imboden's cavalry probed gingerly through woods east of New Market and encountered Federal cavalry facing them. This discovery led Imboden to propose going east of Smith's Creek to attempt flanking the Federal position from that side. While he and Breckinridge were discussing the plan, Sigel finally arrived in the battle area escorted by Companies F and M of the Lincoln Cavalry. Sigel left his staff at Rice's House and rode forward to the battle line to see things for himself. He quickly decided that there was not time for all his forces in the rear to come forward to Moor's original line; consequently, he directed a withdrawal from the original line back to the high ground on Bushong's Hill.

There his flanks would be protected by the Shenandoah's bluffs on the west and Smith's Creek on the east, and he stood a better chance of consolidating his force. Sigel immediately ordered Carlin's Battery to Bushong's Hill and von Kleiser's Battery up to support the withdrawing line. A few minutes later, he directed General Sullivan to bring up the rest of his infantry to the Bushong's Hill position. The literal-minded brigadier complied, leaving DuPont's Battery awaiting orders south of Rude's Hill.

There his flanks would be protected by the Shenandoah's bluffs on the west and Smith's Creek on the east, and he stood a better chance of consolidating his force. Sigel immediately ordered Carlin's Battery to Bushong's Hill and von Kleiser's Battery up to support the withdrawing line. A few minutes later, he directed General Sullivan to bring up the rest of his infantry to the Bushong's Hill position. The literal-minded brigadier complied, leaving DuPont's Battery awaiting orders south of Rude's Hill.

Breckinridge's attack was in full force by this time. The 18th Connecticut skirmishers fell back on the rest of their regiment. The regiment soon extricated itself with some difficulty and fell back with the 123d Ohio to a line about 400 yards farther north, almost on a line with von Kleiser's position on the Pike. About 1230 Sigel ordered Snow's Battery and the 1st West Virginia to withdraw from New Market and to set up on Bushong's Hill, thus vacating the village completely. A half-hour cannonade ensued in the continuing rain.

While that was going on, Imboden moved the 18th Virginia Cavalry and one section of McClanahan's artillery east of Smith's Creek. The 23d Virginia Battalion extended its line to the creek to fill in the gap his departure created. Imboden then moved north to a point where his guns could enfilade the Federal flank. This caused General Stahel to pull his cavalry slightly north, behind a ridge just to the north of the present Pennsylvania monument. Ewing's Battery, now back with the cavalry, engaged the Confederate guns to little mutual effect for the remainder of the day. Imboden then tried to carry out the second part of his task, which was to destroy the bridge over the Shenandoah at Mt. Jackson to block a Federal retreat. He found the water too high to cross to approach the bridge and rejoined Breckinridge at 1600, too late to contribute further to the battle.

The 18th Connecticut and 123d Ohio resisted briefly at their second position, allowing Sigel's final line to form. One of von Kleiser's guns was now disabled on the Pike and had to be abandoned when the battery withdrew. The two infantry regiments were fairly shattered by this time, although Company D of the 18th Connecticut attached itself to the 34th Massachusetts to continue the fight later. Breckinridge immediately pressed forward his guns massed on the east as the Federals withdrew. He used his artillery almost as an assault unit in itself, offsetting somewhat his numerical inferiority while helping to suppress some of the fire of the well-handled Federal artillery.

By about 1400, Sigel's final line was almost fully established. On the west overlooking the Shenandoah bluffs, Company C, 34th Massachusetts, provided support to part of a gun line extending along nearly half of the Federal front.

By about 1400, Sigel's final line was almost fully established. On the west overlooking the Shenandoah bluffs, Company C, 34th Massachusetts, provided support to part of a gun line extending along nearly half of the Federal front.

Union cannon line on a rise that looks over the Field of Lost Shoes. At the far right, between the wheel and the edge of the photo, is the Hall of Valor.

Carlin's West Virginia Battery started on the bluff, and to its left was Snow's Maryland Battery, then von Kleiser's Battery of Napoleons. The 34th Massachusetts next took up the line, just about 350 yards due north of the Bushong farm; the 1st West Virginia was to its east. About 1420 the line was extended from the left flank of the 1st West Virginia to the Pike by the 54th Pennsylvania. It had jogged from Rude's Hill after marching from Woodstock with Sullivan earlier in the day. It was preceded on the field by the 12th West Virginia, which placed five companies behind the 34th Massachusetts and its remaining five about 200 yards behind Company C, 34th Massachusetts, on the Federal right flank. About 1430, Captain DuPont brought his battery up the Pike on his own initiative and held it about one quarter mile north of the line while he watched the situation develop.

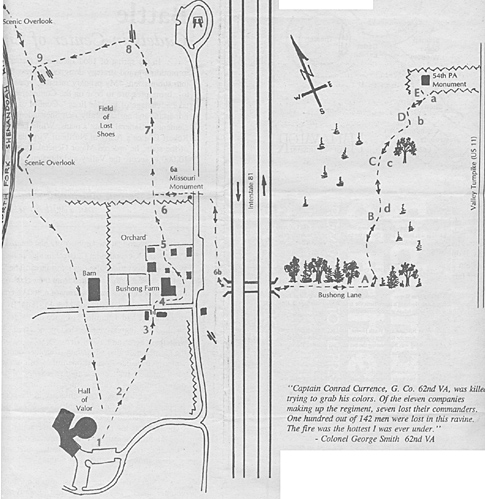

About that time, the Confederate line had reached the Bushong farm after enduring a growing hail of Federal fire. The 51st and 30th Virginia had become somewhat mixed in the advance. The eastern course of the Shenandoah River had squeezed the 26th Virginia eastward behind the 51st Virginia. At the same time, the topography on the western side of the Confederate line had protected the 26th and part of the 51st from much of the fury of the Federal fire. This was not the case for the portion of the 51st and elements of the 30th around the Bushong farm. They had reached the farm's northern fence line, but then were forced back to its southern side. The 62d Virginia on their right had advanced a hundred yards farther before being blasted back with 50 percent losses to a position on line east of the Bushong House. General Breckinridge reluctantly directed that the VMI cadets fill in the gap left by the 51st Virginia around the farmhouse. The cadets moved on both sides of the house to re-form their line in an orchard, and after climbing over a fence, they lay down and exchanged fire with the Federal line about 300 yards away.

The climax of the battle was fast approaching. General Sigel had noted the discomfiture of the Confederate line and ordered a counterattack, but unforunately his orders were not clear and they were poorly executed piecemeal. First, about 1445, the Federal cavalry attempted to charge up the Pike. It rode virtually into the mouths of the guns Breckinridge had set up on the ridge southeast of the Federal line. The cavalry's position was worsened by the response of the Confederate infantry, which briefly faced the Pike on both sides of it, adding a wall of fire on each flank of the quickly decimated Federal horse. The troopers were repulsed with great loss in a matter of minutes. At tbout this time, a violent thunderstorm was adding to the confusion. Confedrate fire continued to build on the Union line. Jackson's Battery was deployed southeast of the Bushong House and one company of the 26th Virginia inched close enough to focus accurate rifle fire on Snow's and Carlin's Federal artillerymen and their teams.

The climax of the battle was fast approaching. General Sigel had noted the discomfiture of the Confederate line and ordered a counterattack, but unforunately his orders were not clear and they were poorly executed piecemeal. First, about 1445, the Federal cavalry attempted to charge up the Pike. It rode virtually into the mouths of the guns Breckinridge had set up on the ridge southeast of the Federal line. The cavalry's position was worsened by the response of the Confederate infantry, which briefly faced the Pike on both sides of it, adding a wall of fire on each flank of the quickly decimated Federal horse. The troopers were repulsed with great loss in a matter of minutes. At tbout this time, a violent thunderstorm was adding to the confusion. Confedrate fire continued to build on the Union line. Jackson's Battery was deployed southeast of the Bushong House and one company of the 26th Virginia inched close enough to focus accurate rifle fire on Snow's and Carlin's Federal artillerymen and their teams.

Meanwhile, about 1500 the second part of Sigel's charge was attempted, and each Federal regiment in line lurched forward more or less on its own. The 34th Massachusetts advanced halfway to the Bushong House; however, the 1st West Virginia on its left moved forward barely 100 yards before it gave up. In puffing pack, it exposed both the New Englanders and the 54th Pennsylvania on its left, which had gallantly pressed into the Confederates. While this was going on, the ire on the Federal guns became so galling that Sigel authorized their withdrawal. He could see the 28th and 116th Ohio, the train guards, drawing up in line of battle near the Cedar Grove Dunker church two miles north at the base of Rudes Hill, and he directed the guns there. The two Ohio regiments had run the four miles from Mt. Jackson. Snow got away with all his pieces; however, Carlin had to abandon two guns because of the loss of horses, and von Kleiser had to leave a second gun damaged by artillery fire. Carlin lost a third gun because it became irretrievably bogged down during the withdrawal.

This withdrawal of the Federal artillery was marked by a decrease in the volume of fire, and Breckinridge sensed his moment had come. A few minutes after 1500 he ordered a general advance. The 34th Massachusetts and 54th Pennsylvania continued to resist valiantly until all the guns that could be were withdrawn. These units then defended rearward until they came under the protection of Captain DuPont's Battery, which delayed skillfully by echelon of platoon back to Rude's Hill.

This withdrawal of the Federal artillery was marked by a decrease in the volume of fire, and Breckinridge sensed his moment had come. A few minutes after 1500 he ordered a general advance. The 34th Massachusetts and 54th Pennsylvania continued to resist valiantly until all the guns that could be were withdrawn. These units then defended rearward until they came under the protection of Captain DuPont's Battery, which delayed skillfully by echelon of platoon back to Rude's Hill.

The Field of Lost Shoes, as seen from the Confederate line, roughly corresponding to the VMI cadet position.

The Confederate line swept over the Federal positions, with the cadets capturing von Kleiser's abandoned gun along with many men from the 34th Massachusetts. Breckinridge removed the cadets from the advance about 1520: "Well done, Virginians, well done, men." Then, impressed by DuPont's opposition and aware of the new Federal line forming on Rude's Hill, he halted his attack about 1600 to reorganize and resupply. The Confederate artillery, including the VMI section, continued to engage the Federal artillery for another hour.

The Federal main body pulled back across the Shenandoah by 1800, followed an hour later by DuPont and a cavalry escort, which burned the pridge. By the time Breckinridge had his victorious force in hand to renew the Lssault, his enemy had fled. Sigel was so eager to get away that he left his badly wounded in Mt. Jackson and marched the rest of his force through the night and next day until it reached Strasburg the following evening.

Aftermath

New Market unquestionably was what some historians have called the "most important secondary battle of the war." It temporarily unhinged Federal plans for the Valley, preserving its resources longer for the faltering Confederate war effort. Even more significantly, it secured the strategic flank of Robert E. Lee's forces, by then seventy-five miles to the east, locked in mortal combat with Grant's and Meade's men. It is not beyond reason to say that the battle extended the life of the Confederacy by nearly a year. This strategic success was one thing; the inspiring example of the VMI cadets was another. Theirs was one of several decisive contributions to the battle, the absence of any one of which would have been fatal to Confederate success. However, this group of young men averaging eighteen years of age were not hardened troops. They were called from their campus to fight for a cause in which they believed. They faced reality unflinchingly and gallantly carried out what was expected of them. Their performance had a lasting positive effect on Southern morale and still inspires their successors.

Breckinridge's masterful performance as both a department commander and tactical leader distinguished him as one of the best of many good Confederate generals.

Breckinridge's masterful performance as both a department commander and tactical leader distinguished him as one of the best of many good Confederate generals.

The tour map of the battlefield.

Success was possible at New Market because of his prompt assessment of the situation and the flexibility he had incorporated into his defense plans. His innovative tactical measures including the use of deception and the aggressive use of his artillery combined with his strong personal leadership to offset many disadvantages. His success was virtually assured by his willingness to accept the risks necessary for victory. Thus, his disregard of the odds and his gamble to hold nothing in reserve at the critical moment were proved fully justifiable. Franz Sigel, on the other hand, was the antithesis of this great Southerner. He displayed excessive caution while failing to think through the purpose or value of many of his decisions. He burdened himself with excessively large trains requiring far too much manpower to guard. His disregard for unit integrity led him to send Colonel Moor forward with a mixed collection of units, few of which had worked together before. His lack of organization led to such things as Captain DuPont's being forgotten in the heat of battle while von Kleiser's short-range Napoleons were disadvantageously deployed.

Sigel failed to use his staff, personally conducting minor-level reconnaissances and deployments. At the same time, he thought too much of strategy and not enough of tactics, completely ignoring the effect of his decisions on the physical condition of his men. His Chief of Staff, Col. David H. Strother, said of him, "There is no trace of cowardice in Gen. Sigel, as there was certainly none of generalship. Sigel has the air to me of a military pedagogue, given to technical shams and trifles of military art, but narrow minded and totally wanting in practical capacity."

Most would agree with Colonel Strother's conclusion. "We can afford to lose such a battle as New Market to get rid of such a mistake as Gen. Sigel."

For a moment New Market made it seem as if another Stonewall had come to the Valley. But, although further encouraging moments were experienced in the summer of 1864, the South was inevitably declining. The promise of New Market soon was buried in Federal generalship and numerical and materiel superiority. Thus, by the time of the battle's first anniversary, peace had come to the Valley on Federal terms. The examples of courage and dedication shown in the battle, however, will endure forever.

Suggested Readings

The Battle of New Market has become one of the most chronicled events of the Civil War in Virginia. The role of the VMI cadets has been the particular object of discussion. Any work about the Institute will have a portion devoted to the battle. Articles and letters in the Confederate Veteran Magazine are a rich source of anecdotes and comment. Unit histories and personal memoirs also invariably provide a few pages of valuable detail on the fight.

Turner, E. Raymond, The New Market Campaign, May, 1864, Richmond: Whittet and Shepperson, 1912. The first scholarly treatment of the battle. Still a sound, balanced work with useful illustrations.

Davis, William C., The Battle of New Market, Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Co., Inc., 1975. The only modern book-length study. Rich in detail, the book tends to take a Confederate perspective.

DuPont, Henry A., The Campaign of 1864 in the Valley of Virginia and the Expedition to Lynchburg, New York: National American Society, 1925. A broader study that tries to place the battle in relation to the full Valley Campaign as seen by the author, a Federal officer and participant.

Order of Battle

15 May 1864

Both the forces engaged were provisional, assembled from scattered forces operating for the most part on security and anti-guerrilla missions. The Federals had been gathered from numerous isolated posts over the six weeks preceding the battle. Few of the units had performed before in standard brigade and division operations. General Sigel had completed assembling his forces at Martinsburg and Winchester on 29 April. He developed his organizational structure during his slow movement south. Even more immediately, the Confederate forces were gathered as the Federal plan revealed itself. General Breckinridge began to consolidate his forces on 7 May, completing his new arrangement at Staunton on 12 May, three days before the battle.

U.S. Department of West Virginia

Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel

1st Infantry Division -Brig. Gen. Jeremiah C. Sullivan

1st Brigade-Col. Augustus Moor

- 18th Connecticut Infantry-Maj. Henry Peale

28th Ohio Infantry-Lt. Col. Gottfried Becker

116th Ohio Infantry-Col. James Washburn 123d Ohio Infantry-Maj. Horace Kellogg

2d Brigade-Col. Joseph Thoburn 1st West Virginia Infantry-Lt. Col. Jacob Weddle

- 12th West Virginia Infantry-Col. William B. Curtis

34th Massachusetts Infantry-Col. George D. Wells

54th Pennsylvania Infantry-Col. Jacob M. Campbell

First Cavalry Division Maj. Gen. Julius Stahel

1st Brigade-Col. William B. Tibbitts

- 1st New York Cavalry (-) (Veteran)-Col. Robert F. Taylor

1st New York Cavalry (Lincoln)-Lt. Col. Alonzo W. Adams

1st Maryland Cavalry (det.) (Potomac Home)-Maj. J. T. Daniel

21st West Virginia Cavalry-Maj. Charles C. Otis

14th Pennsylvania Cavalry-Capt. Ashbel F. Duncan

2d Brigade-Col. John E. Wynkoop

- 15th New York Cavalry-Maj. H. Roessler

20th Pennsylvania Cavalry-Maj. R. B. Douglas

22d Pennsylvania Cavalry (det.)-1st Lt. Caleb McNulty

Artillery

- Battery B, Maryland Light (3" rifle)-Capt. Alonzo Snow

30th Battery, New York (12-lb. Nap.)-Capt. Albert von Kleiser

Battery D, 1st West Virginia Light (3" rifle)-Capt. John Carlin

Battery G, 1st West Virginia Light (3" rifle)-Capt. Chatham T. Ewing

Battery B, 5th United States (3" rifle)-Capt. Henry A. DuPont

Federal Forces

Infantry 5,245 (approx. 3,750 engaged)

Cavalry 3,035 (approx. 2,000 engaged)

Artillery (22 guns) 660 (approx. 530 engaged)

Total: 8,940 (6,280)

C.S. Western Department of Virginia

Maj. Gen. John C. Breckinridge

Infantry Division

1st Brigade-Brig. Gen. John Echols

- 22d Virginia Infantry-Col. George S. Patton

23d Virginia Battalion-Lt. Col. Clarence Derrick

26th Virginia Battalion-Lt. Col. George M. Edgar

2d Brigade-Brig. Gen. Gabriel C. Wharton

- 30th Virginia Battalion-Lt. Col. J. Lyle Clark

51st Virginia Infantry-Lt. Col. John P. Wolfe

62d Virginia Infantry (Mtd.)-Col. George H. Smith

Co. A, 1st Missouri Cavalry (Inf.)-Capt. Charles H. Woodson

23d Virginia Cavalry (Inf.)-Col. Robert White

VMI Cadets-Lt. Col. Scott Shipp

Cavalry, Valley District Brig. Gen. John D. Imboden

- 18th Virginia Cavalry-Col. George W. Imboden

Misc. dets. 2d Maryland, 23d Virginia, 43d Virginia (Partisans)

Artillery Maj. William McLaughlin

- Chapman's (Virginia) Battery (4 how., 2 rifle)-Capt. George B. Chapman

Jackson's (Virginia) Battery (1 rifle, 3 12-lb. Nap.)-1st Lt. Randolph H. Blain

McClanahan's (Virginia) Battery (2 how., 4 rifle)-Capt. John McClanahan

VMI Section (2 rifle)-Cadet Capt. C. H. Minge

Confederate Forces

Infantry and dismounted cavalry 4,249 (approx. 3,800 engaged)

Cavalry 735 (all engaged)

Artillery (18 guns) 341 (all engaged)

Total: 5,325 (4,876)

Casualties

Federal: 97 KIA, 520 WIA, 225 MIA = 841 (13%)

Confederate: 43 KIA, 474 WIA, 3 MIA = 531 + (13%)

Notes on Ordnance

Three-Inch Ordnance Rifle

Fires 10-lb. projectiles (conical bolt, case, shell, canister)

Bore diameter, 3 "

Tube weight, 820 lbs., wrought iron - Range, 1,830 yds. at 5° elevation - Muzzle velocity, 1215 FPS

Use: Infantry support in open areas, counterbattery.

12-Pound Field Gun, M1857 (Napoleon)

Fires 12-lb. projectiles (solid, case, shell, canister)

Bore diameter, 4.62"

Tube weight, 1227 lbs., bronze

Range, 1,619 yds. at 5° elevation - Muzzle velocity, 1485 FPS

Use: Close infantry support in wooded areas, final defense.

Parrot Field Rifle, 10 pounder

Fires 10-lb. projectiles (conical bolt, case, shell, canister)

Bore diameter, 3 "

Tube weight, 890 lbs., iron

Range, 2,000 yds. at 5° elevation - Muzzle velocity, 1300 FPS - Use: Same as ordnance rifle.

Field Howitzer, 12 pounder

Fires 12-lb. projectiles (solid, case, shell, canister)

Bore diameter, 4.62"

Tube weight, 788 lbs., bronze

Range, 1,072 yds. at 5° elevation - Muzzle velocity, 1200 FPS

Use: High-trajectory antipersonnel.

More Battle of New Market: 1864

Back to List of Battlefields

Back to Travel Master List

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 2003 by Coalition Web, Inc.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles concerning military history and related topics are available at http://www.magweb.com