A handful of resolute men plunged into the heart of Asia, smashed huge armies that included European mercenaries, overthrew a very powerful and opulent oriental empire, and established a New Order. The time was not 1870 but 332-1 B.C., the place, Persia. The victories of Alexander the Great had brought to the fore a new tactical system. Beneath the mingled sounds of battle, of rattling war chariots and galloping cavalry, there was a softer note; the steady tramp of heavy infantry. The Macedonian phalanx had arrived, and it would dominate tactical thinking for a century.

The Macedonian phalanx was not an entirely new tactical formation, however, but a development of the old hoplite phalanx, which had developed in turn from still more primitive spear-fighting formations. The Macedonian formation was distinguished from the earlier ones chiefly by its depth and the character of its arms. In its late form the phalanx might have from eight to sixteen ranks, each soldier taking up, according to Polybius, about three square feet when the formation was in close order.

Each hoplite was equipped with a slightly concave bronze shield about 24 inches in diameter, in addition to his helmet, cuirass and greaves. He was armed with a formidable spear (sarissa) which was about 15 to 20 feet long and was probably weighted at the butt. When the phalanx engaged the enemy, each soldier held his pike in both hands and the spears of the first five ranks all projected a yard or more beyond the first rank. in order to attack a soldier in the first rank of this hedge- hog, an enemy with a shorter weapon would have to dodge several spears. The hoplites in the rear ranks of the Macedonian phalanx either held their spears upright or, at the halt, rested them on the shoulders of those before them, blocking enemy missiles.

Basic Unit

The basic unit of the Macedonian phalanx was the file (stoichein), usually of eight, ten, twelve, or sixteen men, according to the depth of the formation. The soldiers of the first two ranks and those of the last rank may be classed as noncommissioned officers. The file leader (lochagos) was picked for size, strength, skill and courage. The second rank soldiers also had to be good men, in order to fill the gaps left by casualties in the first rank. The file-clousers (ouragoi) were "men who surpass the rest in presence of mind," since they had "to hold their files straight," and keep the units aligned properly.

Two files made up a double file (dilochia) under a double file leader (dilochites), twice that number a tetrarchia under a tetrarch. Two of the latter units made a taxis, commanded by a taxiarch or hekatontarches. Two taxes formed a syntagnia or syntaxiarchia.

During the early part of the Macedonian period when the taxis was a square of eight ranks and eight files, it was evidently the important tactical unit and had a staff which consisted of a herald, a signalman, a bugler, an aide and an extra file-closer. These were separate from the body of the formation. Later the staff was attached to the syntagma, now a perfect square of sixteen files and ranks. in theory, every part of these formations could hear a command equally wel

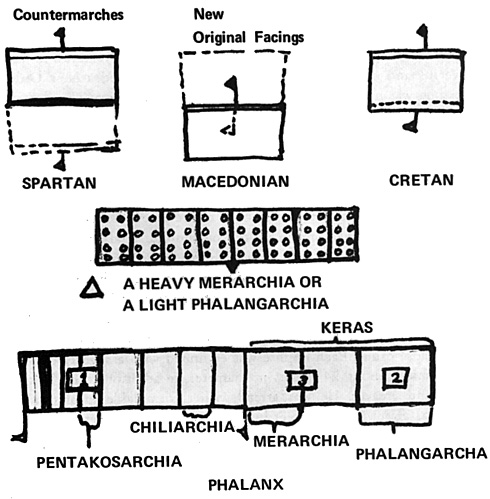

The high divisions of the heavy infantry were

- 2 syntagma = pentakosiarchi

2 pentakosiarchia = a chiliarchi

2 chiliarchia = a merarchi

2 merarchia = a phalangarchi

2 phalangarchia = a wing (keras

2 wings = an army (phalanx)

The respective commanders were, the syntagmataches, the pentakosiarches, the chiliarches, the merarches, the phalangarches, the kerarches, the general (strategos).

When placed in line of battle, the best phalangarchia was posted on the right, and the second and third formed the left wing, with the least reliable as the left half of the right wing. In this way, the commander could equalize the strength of his two wings.

The first thing a war games enthusiast organizing his own little phalanx should remember is that organization here is by file and not by rank. Perhaps it would be best to start with the square unit, either the taxis or the syntagma, if you favor the deep order.

The merarchia had 2 chiliarchia, 8 syntagma and 16 taxes. If the 16 man basic unit were used, it would have had a strength of 2,048 men, if the 8 man 1,024. The front of the whole unit was about 256 yards in open order, half that in close order, or a quarter of it "with shields locked."

Personally, I would prefer that any representation be on a one figure for 16 basis; and at least four ranks deep, in order to give the impression of mass. I would suggest using either the syntagma or the pentakosiarchia, depending on whether you prefer using the 16 man or the 8 man file. In either case, the base would have two rows of 4 figures.

Jack Scruby makes 20 mm Macedonian figures, but you have to make your own sarissas to arm them with. Other manufacturers you might check for war games' figures are Hinton Hunt and Miniature Figurines.

As far as I Know, no one makes a collector grade Macedonian hoplite. The long pike is quite a problem to both the war gamer and collector figure manufacturer.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

1. Polybius, The Histories, With an English Translation by W.R. Paton. London: Wm Heinemann, 1922-7. See Book XVIII: 28-32.

2. Aeneas Tacitus, Asclepiodotus, Onasander, With an English Translation by Illinois Greek Club. London: Wm. Heinemann, 1962.

3. Xenaphone, The March up Country, tr. by W.H.D. Rouse. New York, New American Library, 1959.

More Macedonian Phalanx

Back to The Armchair General Vol. 1 No. 5 Table of Contents

Back to The Armchair General List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1999 by Pat Condray

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com