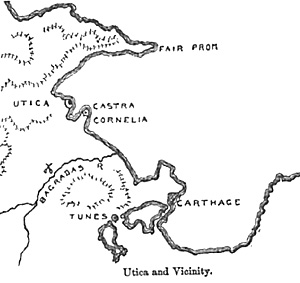

Curio marched overland towards Utica. "Curio sent Marcus ahead to Utica with the fleet; he himself began to make his way there with the army and after two days' march reached the river Bagradas. (The valley of Bagradas was an ill omened place for Romans. During the first Punic War, Regulus was taken prisoner and his Consular Army was destroyed there -slp) There he left his lieutenant, Gaius Caninius Rebilus with the legions while he himself went ahead with the cavalry to reconnoiter Castra Cornelia "...since that place was thought highly suitable for a camp." (CW II 23. 4.)

Curio marched overland towards Utica. "Curio sent Marcus ahead to Utica with the fleet; he himself began to make his way there with the army and after two days' march reached the river Bagradas. (The valley of Bagradas was an ill omened place for Romans. During the first Punic War, Regulus was taken prisoner and his Consular Army was destroyed there -slp) There he left his lieutenant, Gaius Caninius Rebilus with the legions while he himself went ahead with the cavalry to reconnoiter Castra Cornelia "...since that place was thought highly suitable for a camp." (CW II 23. 4.)

Casta Cornelia, (Cornelius' Camp) was the main camping area for Publius Cornelius Scipio, the great Africanus, after he brought his invading army to Africa, in 203. It was still reasonable intact after all these years and would have made a good marshaling place for Curio's invasion but Attius had anticipated Curio's thoughts and planned accordingly.

Appian explains: "While Curio was still on his way from Sicily, his opponents in Africa, expecting that his ambition would make him occupy Scipio's Camp because of the splendor of Scipio's achievements, poisoned the water. Nor were they disappointed; as his second in command took up his position there and his troops immediately fell sick When they drank the water, their vision became fogged and a deep torpid sleep ensued which was followed by frequent vomiting and spasms." (BC II. 44. 4.) Sounds like a form of alkaloids. sfp

While Caninius was dealing with this sudden epidemic, Curio with his 500 horse pressed on to Utica. Attius was taken by surprise. He had a legio at Hadrumetum, and his ally King Juba of Numidia had not brought up reinforcements. It sounds like Attius was counting on the poison to slow Curio down, there was less then a legio (about seven cohorts BC 44. 1.) at Utica's camp. While Curio was harassing a Pompeian supply train, Attius defended with what troops he had. Juba had sent 600 light horse and 400 skirmishers, to Attius the day before. Juba was an ally of Magnus since "... Juba had a traditional bond of friendship with Pompey's family; he also had a grudge against Curio, because the latter as tribune had proposed a bill making Juba's kingdom State property" This had been done in 50. It would have made the kingdom into a Roman province -sfp

The light horse did not fair well against heavier, presumably veteran Gaulic horse. " The cavalry engaged; and the Numidians were unable to withstand the very first impact of our men, but withdrew to their camp by the town with the loss of about 120 men." (CW II. 25. 2-3.)

Once the unfriendlies were driven away, the legio was confined to its camp and Curio had naval control of the waters with Marcius' fleet, so he was able seize all the Pompeian supply ships and order his men to escort them to the Cornelian camp. When he returned to camp, he met his ailing troops on the outskirts, Rebilus, having abandoned the cursed area. When they heard of his victory, the troops crowned him "Victor," and morale rose accordingly. Curio marched them to Utica. (The captured supply ships are not mentioned, but they must have been ordered there as well) this took a day. When he got to Utica, Curio found that Attius Varus had prepared for a siege with his garrison. Curio accepted the challenge. He started his own camp, but before he could finish he was interrupted.

"Before the fortifications of the camp were completed, the cavalry on guard reported that large reinforcements of cavalry and infantry sent by the king (Juba) were approaching Utica; at the same time a great cloud of dust came into view and in a moment the head of the column was in sight. Startled by this unexpected development, Curio sent out cavalry to bear the brunt of the initial onset and hold them up, while he himself quickly withdrew the legiones from the defensive works and drew them up for battle. The king's force had been marching along without apprehension, not troubling to keep in order, and being in consequence unable to manoeuver and in disarray, they were routed when our cavalry engaged, before our legiones had even time to deploy and take up their positions. The royal cavalry escaped almost unharmed, since they raced along the shore and took refuge in the town, but a great many of the (Numidian) infantry were killed." (CW II. 26. 2-4.)

So far the campaign had gone well, except for the brief poisoning, Curio's troops were in good morale, and had inflected several defeats upon Varus' Numidian ally, and seized his supplies. However now things began to change. Curio had left his better legiones at Sicily since the island was critical to Caesar's supply situation. He had brought two who had formerly been Pompeian, likely to toughen them up in a easy campaign. (Remember, Varus had two under strength legiones. (BW II. 44. 1.) These had surrendered to Caesar at Corfinium in Italy, and consisted of 20 cohorts of troops from the Marsi, and the Paeligni (both renowned for their fighting abilities, like most Oscans). (CW I. 16. 6)

They had taken the oath of allegiance to Caesar, but apparently being in close proximity of their former friends some started to waver recalling their old oaths. Caesar tells us " On the following night two Marsian centurions deserted from Curio's camp with twenty-two men from their centuries and went over to Attius Varus. Whether they were expressing their real opinion to Attius, or whether they were saying what he would like to hear (for we readily believe what we wish were so, and we hope that others feel as we do), at any rate they told him that the whole of Curio's army was disaffected, and that it was highly necessary that Attius should come face to face with the army and give them a chance to talk with him. Attius was convinced, and on the following morning he led his legiones out of camp." (CW II. 27. 1-4.)

Curio did the same. This one of the most vexing thing about Caesar's reporting, we started with a legio at Utica, now we have legiones. Since the annies were similar in strength (BC 11. 44. 5.) this meant the addition of another legio. From where? It would seem that Attius had decided that the decisive battle would at Utica, and brought his second legio from Hadrumetum. When? It would appear when Curio went back to the Cornelian camp. Hadrumeturn is about 80 miles from Utica, however. So that is a two day march at least, three days ideally. There are two possibilities. 1. That Caesar greatly underestimated the time it took for Curio to organize his army from illness and march on Utica, though the camp is a mile from Utica in straight line, the terrain meant a detour of 6 miles. (CW II. 24.4) Caesar knew this, and presupposed that this was the case therefore his estimate of a day. 2. The second legio were Numidians trained to fight in the Roman style. We have no proof of this except by their horrible showing during the following battle.

It likely was the first. Events seem to prove that this is correct. If the most of the army was suffering from poisoning, they would not be ready to march the next day. It would take at least three days to recover, (food poisoning takes forty-eight hours to recover from on average) and another day to march the 7 miles to Utica. That would mean four days. This meant that Varus would have time to bring his legio to Utica, as well as request additional Numidian reenforcements. The Numidians arrived around the same time as Curio, Caesar claims. If that is really what happened, then a delay of at least three days would about right.

Deployed

To continue: with both armies deploying, a Senator, S. Quintilius Varus, who had also been at Corfinium, emerged in front of Curio's legiones.. Varus attempted to recall his former comrades to their original oath. He first appealed to their mutual friendship, then promised monetary rewards if they deserted. They did neither. However their morale was shaken by the encounter.

The text is highly corrupt during this passage. Something happened to upset Curio's troops, not enough to force them to defect, but enough of a something that made them want to leave the area. What this was is never explained, since words are missing. Varus may have been involved in the Religio and he foretold the troops doom because they broke their oath, which is speculation. It does figure strongly in Curio's following speech, however. -sfp

Curio was forced to hold a council of officers to determine the armys attitude. During this meeting two opinions were expressed. One was storm the camp at once. The other was retreat to the fleet at Cornelia, and return to Sicily. Supposedly the troops were that demoralized. Curio could not storm the camp, it was two strong. Nor would he retreat. He decided to appeal to the troops and went before them and made a speech.

Caesar tells us "He dismissed the council and summoned an assembly of the troops. He reminded them how their zeal had helped Caesar at Corfiniurn and how thanks to their good-will and their example he had won over the greater part of Italy. 'You and your action,' he said, 'were subsequently copied by all the townships, and it was with good reason that Caesar entertained the most friendly feelings towards you, while his opponents thought very ill of you. For Pompeius suffered no reverse in battle; what dislodged him and made him leave Italy was your action, which foreshadowed what was to come. Caesar has entrusted to your faithful keeping myself, whom he held very dearly, and the provinces of Sicily and Aftica'. Curio is referring to the value of the corn producing ability of both to sustain Italy in a long war -sfp

He then told them about Caesar's victories, and how the Caesarians are winning the war with their successes in Spain. Now he gets down to real crux of the matter, the fact that they are condemned oath breakers: "They say that you have deserted and betrayed them and they mention your first oath. Did you really desert Lucius Domitius, commander at Corfinium or did Domitius desert you? Was it not he who abandoned men who were ready to endure all that fortune might bring? Did he not try to save himself by running away, without your knowledge? You were betrayed by him; and was it not by Caesar's kindness that you were spared? How could you be held by an oath, when the general himself threw away his symbols of office, Curio could be referring to the rods and axes, the symbol of a Roman magistrate abandoned his command and became a private individual - and was then himself captured and came under the power of another? We are left with a new theory of obligation, that you should ignore the oath by which you are bound and uphold the one which was canceled by the surrender and loss of rights of the general. POWs in the late Republic forfeited their citizenship, until released.

But perhaps you are satisfied with Caesar, and your grievances are against me. I do not intend to recount the services I have done you; they do not as yet come up to my intention and your expectations However, soldiers always look to the outcome of a war for the reward of their labors; and even you have no doubt what the outcome will be. Indeed, why should I omit mention of my own conscientiousness or, as far as things have gone, my fortune? I brought the army over safe and sound without the loss of a single ship; do you have any complaint about that? On the way I scattered the enemy fleet at the first encounter. Twice in two days I won a cavalry battle. I took two hundred vessels and their cargoes right out of the harbor, at Utica out of the very grasp of the enemy, and so robbed them of the ability to get supplies either by land or in ships. Scorn such good fortune and such leaders; choose instead the disgrace at Corfinium, the flight from Italy, the surrender of Spain, which foreshadow the result of the war in Affica. I indeed chose to call myself a soldier of Caesar's; you have hailed me as your "victor." If you have changed your minds, I return your gift. the title. Give me back my own name, in case you should seem to have bestowed the honor on me in mockery.' (CW II 32. 2-8.)

If this speech is correct and Caesar is not making it up, then we indeed see the problem. Oathbreakers were cursed. And Varus had done something to recall this to the army who was at Corfinium, that they were oathbreakers. He probably pronounced them "sacer." Curio not only cleverly attempts to remind they never broke their oath since their commander deserted them, instead he broke his oath to them releasing them from theirs. Next he reminds them, that they are on the winning side, finally that he himself is a lucky commander as well.

This restored the morale of the troops and they begged to lead against the enemy. A Roman legionary in battle fervor is something that could not be denied, except at the peril of the commander, so Curio let them out and formed line of battle. There was a small valley between them and the enemy camp. (CW II.34.1.) So both armies deployed on the plateaus across from each other. Attius sent his Numidians light infantry stiffened with Numidian horse into the valley,

Curio responded by sending two cohorts and his horse. The Numidian cavalry remembering how effective the Gauls were, fled leaving the skirmishers to be cut down. Reblius told Curio that now was the time to strike. Curio reminded the legiones of request the day before, and lead them into the valley. On the face of this it was suicide since the enemy held the high ground.

However Caesar tells us: "The going in the valley was so difficult that those in front could not climb out easily without help from their comrades below. With the minds of Attius's men taken up with their own fear, and with the rout and the slaughter of their comrades, and they had no thought of resisting; indeed, they all believed that they themselves were already being surrounded by the victorious cavalry. And so, before a pilum could be hurled or our men could get any nearer, the whole of Attius Varus's army turned tail and fled back to their camp.

During this retreat, a certain Fabius, a Paeligulan from the lowest ranks of Curio's army, caught up with the head of the retreating column and began looking around for Varus, (S. Quintilius Varus) calling for him loudly by name, so as to appear to be one of his own men who had something to tell him. Varus, hearing his name called several times, stopped and asked the man who he was and what he wanted; Fabius then aimed a blow with his sword at his exposed arm and very nearly killed him. Varus, however, escaped by lifting his shield to parry the blow. Fabius was then surrounded and killed by the troops who were nearest.

The fleeing troops were so numerous and so disordered that they blocked the gates of the camp and obstructed the way. More men died there, without being wounded, than perished in the actual battle or the retreat, and they were very nearly driven out of the camp as well. Some of them carried straight on into the town. However, the nature of the ground and the fortifications of the camp denied Curio's men access, and besides they had marched out to give battle, and did not have with them the necessary equipment for an assault on a camp. Curio therefore led them back to camp. His only casualty was Fabius; on the other side, about six hundred were killed and a thousand wounded." (CW II. 34. 3-6. 35. 1-3.)

It was a total rout, even if we chose not to believe Caesar's absurd casualty ratio. Attius and Varus attempted to shore up camp defenses, but so many legionarii had fled into the town that Attius decided that the camp could not be held and withdrew his whole force into Utica later that night. The fact that the legiones were so demoralized by the loss of their light infantry, is worth remarking on. This is why I suspected that one legio may have been composed of Numidians. It also worth noting that the name of the Legatus of the second legio in Africa, (G. Considius Longus) is never mentioned.

The next day Curio's jubilant troops found that Attius had withdrawn. They immediately prepared a line of works that would eventually wall off the town. The citizens of Utica had enough. They knew what would happen if the town was stormed and they were delivered into the tender mercies of Curio's men. Many of the Romans living there favored Caesar, and all were unwilling to lay down their lives for Magnus. They demanded Publius Attius to surrender his forces, and withdraw from Utica. Attius was on the verge of doing this very thing. Then came word from Juba. The King was approaching with a large army to save Utica.

Curio had heard the same thing. Rightly figuring that he would be outnumbered in horse, he decided to withdraw back to Camp Comelia, fortify, summon the rest of his forces, and wait for their arrival, which he did the next day. While at Cornelia (the springs must have been clear by now) deserters from Attius were brought before him. They told him the King was forced to turn back to put down a revolt, leaving one of his trusted princes Saburra with only part of his army. He changed his plans, and by doing so, sealed his doom.

More Curio in Africa 49 BCE

Back to Strategikon Vol. 1 No. 2 Table of Contents

Back to Strategikon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by NMPI

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com