$pace

$pace

Most people think of space as vast and empty, a place filled with precisely nothing. They think that space is a giant collection of particles and gases and growing and dying stars.

They're wrong.

what is it?

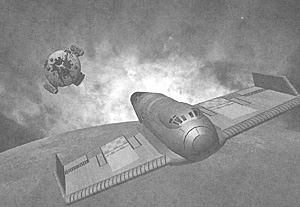

The Linnengart is probably the most common low-budget explorer in space. The design is nearly a decade old, and so far it is Pioneer Shipworks' only entry into the commercial exploration market.

The original concept was the brainchild of shipwright Sandra Knowels. A bit of an eccentric, she had a reputation for crafting unusual (and impractical) vessels. Ten years ago, Pioneer Shipworks was a mediocre freighter manufacturer, and wanted to try something new. When Ms. Knowels approached them with a viable explorer design, they gave her their complete support. The end result was a unique vessel with an unusually high endurance for a ship of its size and class.

The name Linnengart was taken from an old Earth captain, Christian Linnengart, who still holds the record for the highest number of hours logged in space.

what does it do?

what does it do?

The ship is essentially a mobile sensor platform. It allows the intrepid entrepreneur to produce planetary surveys detailed enough to be sold in the commercial market.

The bare technical schematics of the Linnengart are listed throughout this pamphlet. Some of the more important features are listed here and our sales staff is trained to answer all of your questions.

a happy customer

"Space is filled with money, son."

My father used to say that.

"No, it's ain't floatin' around in big interstellar clouds waitin' for someone to come along with a net, either. It's hidden. You gotta look for it.

"It is in the form of unseen planets and asteroids orbitin' weird little stars somewhere out on that frontier." He'd point at some stars he didn't know the name of. It won't come to you... you gotta go to it."

It's true. It was my father's belief that space could make any man rich. Any man could make his dreams in space. With the right, how did he put it? Gumpshun!

When my dad was around, there was no low cost Linnengart probe either. Well... now there is.

the eyes in the skies

the eyes in the skies

The Linnengart has the largest passive sensor array commercially available. But, just because it's big doesn't mean it's sensitive. In fact, the array is a little sub-standard, and it relies on its size to boost performance. To make matters worse, the Linnengart has unshielded mechanical and electronic equipment in front of the array. Operating any of these systems, like the docking arms, impairs its scanning capabilities. Passive scans are impossible while launching probes or docking/undocking the shuttle.

The passive array is sensitive enough to pick up the energy emissions of a small camp fire from orbit. It is capable of detecting energy in bandwidths ranging from the lower infra-red to the Lipper x- ray. Think of the sensor as a portable radio telescope, without the capability of beaming signals. Note: The passive array cannot be used by itself for mapping surveys.

The active arrays have better- than- average performance... under normal conditions. Each array can be independently configured and aimed; however, all four arrays can be linked in order to produce highly detailed scans.

With a single active array, a Linnengart can survey 1.3 million square kilometers in an hour. It can conduct a detailed and accurate mapping survey of an Earth-sized world in about 3 84 hours (16 days). If additional arrays and remote probes are used to help, divide the time given above by the total number of arrays and probes in use.

All the active arrays are "surface penetrating" and may probe through low density material (like soil) to uncover mineral deposits that lay buried beneath a planet's surface from orbit (it's always a good idea to go down to the surface and verify any findings, just to be sure). The ship's factory-bUilt arrays can penetrate down to about 15 meters. Advanced sensors can increase this depth to almost a kilometer, however devices with that kind of power costs thirty million credits or so, and that's increases the cost of ship by 300% or more.

Surface penetrating scans cannot see through rock, metal, or

any substance of similar (or heavi. :) density. They can, however, be

adjusted to pass through large v ames of water to reveal ocean floors

and lake beds. This is simply ,-, ~riatter of fine-tuning the scanning

beam frequency (although it may take a few hours to get a clear

picture). An active array cannot perform penetrating scans while also

survey mapping.

Surface penetrating scans cannot see through rock, metal, or

any substance of similar (or heavi. :) density. They can, however, be

adjusted to pass through large v ames of water to reveal ocean floors

and lake beds. This is simply ,-, ~riatter of fine-tuning the scanning

beam frequency (although it may take a few hours to get a clear

picture). An active array cannot perform penetrating scans while also

survey mapping.

The active arrays can also provide pictures of ground sites, with a clear resolution to within a square centimeter. Unless the ship (or a probe) is in a geosynchronous orbit, it is difficult to actively watch activity at ground level. Usually an orbiting vessel has only a few seconds of lingering time over a given area, and will only have enough time for a few scans.

All the scanning times and capabilities mentioned above are accurate only under ideal conditions, i.e. no extraordinary terrain features, through a clear atmosphere, and free from any interference such as solar flares, intense weather conditions, or marauding pirates. Any complications will greatly increase scan times, or in the worse scenarios, will make scans impossible.

wandering eyes

The Linnengart is equipped with four remote sensor probes. Each probe can be considered the equivalent of one of the ship's active arrays, minus the penetrating scan ability. The probes can be operator-guided, but are intended to operate autonomously, freeing up the crew for other duties. These probes are intended to be reusable, and once their job is done, they return to the ship.

Versatility is the main feature of these probes. They can carry any standardized sensor package on the market, provided it fits into the payload bay. Pioneer Shipworks' Swap-It" modular framework allows instrument packages to be exchanged in less than an hour, even if working in space.

The bad part: the probe launchers are almost completely external. Engines and the fuel systems are the only things which can be serviced from the inside of the ship. Everything else must be accessed from the outside, which requires space suits and extra time must be budgeted for even simple maintenance. The probes themselves suffer from a limited fuel supply, and it is not at all unusual to send the shuttle to retrieve a probe that has run out of gas. Once the probe is retrieved, a space walk is necessary to return it to its launcher.

restricted accessibility

One last thing about the Linnengart: it is incapable of entering an atmosphere, and does not have rudimentary landing gear. This is probably the ship's greatest handicap. Most vessels this size, even if unstreamlined, are equipped with landing gear and can touch down on airless worlds or take advantage of a station's internal facilities. The Linnengart is restricted to external facilities and docking ports. The ship relies heavily on its shuttle for transferring supplies, fuel and passengers.

It seems natural to assume that the auxiliary shuttle featured in all the brochure illustrations is part of the basic Linnengart package -- it isn't. However, Pioneer Shipworks will happily throw one in for a little extra handling fee. It's a repulsive little trick, considering the shuttle is essential...

- "IF I had it to do over again, I would

punched that squirrely little sales-boy square in his

head when he asked me iI` I wanted to add the

SHUTTLE! After I said 'yes', he asked me if I would

need to add a life support system."

gravity!

It is definitely a comfort to feel the floor underfoot during long stays in space. The ship can simulate up to 2Gs of gravity under maximum thrust. This doesn't happen too often, as the main drive's performance (and crew comfort) is greatly reduced at thrusts over IG. Like all human ships, the Linnengart has no means of compensating for inertia. High thrust alarms sound automatically when engine output exceeds IG, warning everyone to strap down before they get hurt.

Most ships have one big drawback: if the engines aren't firing, there is no gravity. The Linnengart does not have this problem. The crew quarters, main work stations and cargo decks are part of a rotating section which can simulate up to 0.4Gs. This is a luxury unheard of on all but the largest Earth ships, and it is the secret to the Linnengarts endurance. Crews can stay out much longer without worrying about the effects of low and micro gravity environments.

The main difference between these two gravity types is the orientation of the floor. All the floors in the rotating section are oriented for spin, although this makes it harder to get around inside the ship while under thrust. Staterooms can be easily adjusted between thrust and rotation. Bunks are strung up like hammocks and can swing freely depending on which way is down. Command and control stations are too bulky to be modified-while under thrust the bridge crew is effectively working lying down.

care and feeding

Space travel puts a great deal of stress upon a vessel, and eventually all sorts of problems arise. The Linnengart is no exception. Monthly maintenance is a must, and there will always be something to fix somewhere. Because of the rotating section, the Linnengart does have a few things which need extra attention. The most expensive of these is the counter-rotating gyro.

This annoying piece of machinery is designed to keep the rest of the ship from spinning while the habitation section is rotating. It is custom-designed at half the size of a standard gyro, and consumes a great deal more power than it should for its size. Maintenance is difficult, costly, and time-consuming. Typical problems include metal stress and fatigue, viscosity breakdown, and anything else that tends to plague large moving parts. If the gyro should fail completely, it often cannot be repaired. Most stations, especially on the frontier, do not waste valuable storage space on such unique items. In fact, the only place guaranteed to have spare gyros is Pioneer Shipworks, back on Earth. The Linnengart owner is expected to pay all transportation costs.

To reduce wear and tear, most captains do not operate the rotating section at full capacity. Some run it at a reduced speed, generating as little as OAGs. Some refuse to engage rotation unless on extended missions. These precautions do extend the life of the gyro, but sooner or later, everyone has to pay that cost.

Crews not used to the stress of rotational gravity tend to overlook another problem area: plumbing. Both the fresh water and sewage tanks are stored in the ship's cargo sections, and must be pumped "uphill" past the rotation hub. Whoever designed this has never been in space. These pumps must be inspected regularly. They are normally capable of handling the workload, and not often prone to failure. But if one pump does give way, it puts a greater strain on the rest of the system -- a strain that a poorly-maintained pump may not handle. For fresh water, pump failure is merely an inconvenience -- the water flows back into the holding tank, but nothing traumatic will occur to the system. Waste disposal failure is a bit more serious. "Downhill" drainage dumps the sewage right back into the habitation section, and that's when the real problems start...

home improvements

home improvements

As soon as there is enough money in the bank, consider replacing the passive sensor array. The computer core, fuel system and recycling filtration systems should also be replaced or upgraded as money allows.

But first, get guns. Neither the Linnengart nor the shuttle are available armed. This is an unacceptable condition on the frontier, and an open invitation to pirates. Emplacements can be added at any ship yard, providing the proper licenses have been obtained.

The Linnengart's large sensor platform is an ideal weapon mount. The easiest installation replaces an active sensor array with a hard point. Power conduits are already in place, and most legal civilian weapons do not draw more energy than the existing power grid can handle. The only drawback with this position is an obscured aft firing arc - especially when trying to shoot around the rotating section. Interrupters can be built into the guns to keep them from accidentally blowing off a cargo hold, but that doesn't solve the problem of having a constant clear shot aft.

A good secondary weapon mount is the engineering section, on top of the reactor housing. Power is easily accessible, and an obscured rear arc is no longer a problem.

The probes cannot be armed with anti-ship weapons. The probe generators are too small, the power grid overloads easily, and there would be no room for sensors.

Keep in mind the Linnengart is not a combat vessel. It is tempting to take advantage of the large forward platform to mount huge numbers of guns, but only a limited amount of power can be drawn before the ship's gyro becomes affected. If too much energy is diverted, the ship becomes unmaneuverable and unstable as it begins to counter-spin. There is no problem if the rotating section is not active during combat. However, several minutes are needed to bring the section to a stop, and combat is commonly over by then.

adapting for game play

The Linnengart works well in settings which rely on a more realistic approach to ship functionality - that is, no artificial gravity, no "magic" planetary landing capability, no inertia control, and so on.

The Linnengart is not capable of interstellar travel by itself. For games such as The Babylon Project and The Jovian Chronicles, this is not a problem. If the ship needs faster-than-light drives, it moves a little slower than the average ship speed. It does have an impressive fuel capacity, and can travel farther than most equivalent vessels. For example, in Traveller the Linnengart would have a Jump-1 capability, but only enough fuel to allow for four jumps.

When filling in details, a general rule of thumb for this ship is "not better, but longer."

how much is it?

The Linnengart is one of the least expensive ships available to commercial explorers. It is available new for around nine or ten million credits. Financial institutions are quite willing to field loans to prospective buyers on the longevity of the design alone - shop around for the best deal!

This ship can be bought used for around two or three million. This may seem like a bargain, but in the long run, increased maintenance costs make this option very expensive. Don't forget to hire a certified astronautical engineer to perform a thorough inspection before a purchase offer is made. Some ships suffer more from wear-and-tear than can be easily seen. Some dealers deliberately hide problems. Whatever the reason, a trained professional is a good asset to have when sorting out the gems from the junk. Also, banks and insurance companies frown on owners who can't be bothered to examine their ships, even though these institutions will insist on doing inspections of their own.

so how about it?

There are some problems with the Linnengart that most other ships of its size do not have. The rotating section causes endless headaches. Maintenance is a heavy drain on finances.

On the other hand, there is gravity. The crew doesn't have to worry about the debilitating effects of long missions in space. The Linnengart is equipped to perform surveys of up to sixty days -- twice as long as most other ships. But most importantly, it's cheap. And for starting entrepreneurs, that's the best advantage of all.

Pioneer Shipworks Linnengart Class Explorer Spaceship

Back to Shadis #51 Table of Contents

Back to Shadis List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master List of Magazines

© Copyright 1998 by Alderac Entertainment Group

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history articles and gaming articles are available at http://www.magweb.com