Unit Formations of European Type

Unit Formations of European Type

These weaknesses did not take anything away from the mens' courage, but demonstrated to Sasori the necessity of a new revolution; the formation of units trained and officered in the European style.

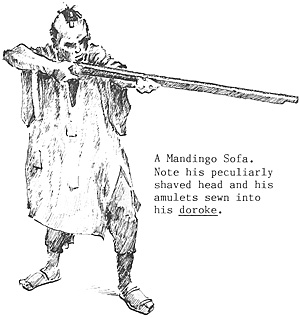

A Mandingo Sofa. Note his peculiarly shaved head and his amulets sewn into his doroke.

Sasori had realized very early, probably as soon as 1885, that he had to reform and retrain his armies if he was to survive. From that time the labor force he was obliged by treaty to provide to the French included not only blacksmiths (who were instructed to study the colonists' arsenal), but also sofas who studied French training techniques. In 1886 French observers made no mention of European style troops in Samori's forces, but in 1887 at Bisandugu the French first noticed the guards who were characterized by their rapid-fire rifles and their blue and red uniforms. A Frenchman noted that Samori referred to the guard as 'my sharpshooters (Tirailleurs)", but the French were unaware of the type of training they were receiving.

It was not until Samori efficiently crushed the Great Rebellion against his in 1888-90 that the French realized the nature of the force now opposed to them.

The number of retrained Sasorian "regiments' grew rapidly, and the majority of thee were to be sent against Combes and Humbert. Starting in 1890 they were officered by one of the best guard leaders, Kato-Alasa, who had just repressed the Great Rebellion in the East. This 'war minister' was to be killed a year later by the French.

In order to implement this new training, Samori welcomed deserters from the French and British armies. However, it seems unlikely that he actually encouraged any significant numbers of his own soldiers to enroll in the enemies' armies as alleged in the so-called 'winter school" legend.

According to this legend, Sasori encouraged his followers to desert to the French armies at the start of the rainy season, where they displayed remarkable heroism and learned novel war techniques. Subsequently, they rejoined their master at the beginning of the dry season when extensive maneouvers began. They were often granted high commands. Soldiers among the whites, they became generals of Samori's army.

This legend is primarily based on the case of Kuruba Musa, a sofa leader who deserted at the time of the Archinard attack and spent all of the winter of 1891 at Kankan among Mangin's Spahis. He displayed great loyalty and a "sense of chivalry" according to Baratier. He was dispatched to warn Kankan during the critical hours of September 3, 1891. He faithfully performed this mission and then returned to report before quietly going back to Sasori. From then on he was in charge of training the bolas in a European fashion. He led his Sofas in the toughest fights against Huebert, and allegedly avoided firing at Mangin, his former superior.

This remarkable case is reported by tradition, but it is an isolated incident and not the result of Samori's plan. Kuruba- Musa was undoubtedly instructed to spy on the Kankan garrison as well as to study the French techniques. He was noted for his heroism but he was certainly not the only spy of the Alamamy in the Dyula metropolis. One could even surmise that he was partially responsible for the French defeat on September 3rd.

The French insist that the case of Ngolo was similar but he say well be a legend. Tradition denies that the leader of the Dabadugu sofas had ever served under the whites, and what we know of his life confirms that. We have to conclude that Sasori did not systematically encourage his faithful to enroll with the French, to become generals in his armies after their experience with the French or British.

The training of the Sofas was usually performed by deserters who were paid a high price for their expertise but received no significant commands or leadership. This is undoubtedly the case of the West Indies Regiment men whose bodies were discovered in British uniforms in 1892 by the French Tirailleurs. A few weeks earlier, in April, Captain Kenney interrogated the instructor of a company of Bilali sofas. This former corporal was not a deserter, as he had been discharged by the French. Once free, however, he had joined Sasori because he 'wanted to fight among his people.'

We have little knowledge of these men, first because they played a modest role, and secondly because such deserters would have been executed if caught by the French and so had every incentive not to be noticed.

The case of the small number of military prisoners captured by Sasori was somewhat different. They could not refuse to serve without jeopardizing their lives. In IB97 Sasori kept nine constables from the Henderson column to work the artillery pieces which he had seized. They participated in the Kong siege, but were then freed as Sisori began his massive withdrawal to the south and Cast.

'European' trained units received their customary coosands in French, and learned how to shoot more accurately in volleys, as well as to fight with the bayonet and maneouver to the bugle's tune. It is true that certain bugle tunes were given a whimsically different meaning.

For instance, the French army call "soup is on" meant 'retreat' to Sanarian forces. The men of Ngolo were already maneouvering to the bugle in 1892. According to one story, Lt. Mazerand, leading a French force skirmishing near Dyasanko, heard the "cease-fire" bugle-call and immediately stopped his men only to be shot dead in an ambush. "It was the bugle of Ngolo that was sounded." But the Samorian armies used the bugle not for deception but for disciplined communication.

We do not know how many of these trained units were in existence at any one time, but Sasori formed a new one each time that weapons and instructors were available to his. The 150 men seen training at Bilali in 1892 clearly formed such a company. They were to rejoin the Alamamy upon completion of their training.

These men primarily fought the French and suffered very heavy losses in 1892. The strategic retreat undertaken by Samori as early as 1892, however, was not detrimental to their training and morale. Both the victories in 1894, and the defeat of the Monteil column were, for the main part, their responsibility.

This training excluded men using flintlocks, so the Alamamy was soon to reach a threshold as the number of his modern weapons peaked, The numbers of trained Sofas, therefore, probably did not increase between 1893 and Sasori's fall in IB99. In spite of significant progress it is clear that he did not succeed in equipping all of his men with modern rifles. This resulted in a clear differentiation between the Sofas uniformed in red and blue and armed with modern rifles and the less orderly bolos.

A French prisoner noted the difference between the four companies of Sofas that marched silently in rows of four before the Alamamy, while the bolas walked in disorderly rows of twenty while shooting in the air and yelling. The new units marched to the bugle, but those who played it had been trained locally and played improvised tunes which sounded strange to French ears. The only conventional bugle tunes were those of the guard, but they were played by the mulatto Braulat, who had been captured during the Bouna affair. He was killed immediately following the battle of Dwe when the victorious Samorians fought the French under Lartigue.

Samori may have extended logic a little far when he ordered that all of his ten who fought like whites should also dress in European clothes. Instead of requiring that they wear a 'Tirailleur' uniform like the elites of his guard or the Dabadugu sofas, he would let them wear a variety of old clothes in a typically whimsical African way.

The proportion of unregisented soldiers as compared to the rest of the army should not be ignored. Including the guard there were 1,000 trained and uniformed men out of a total of 1,400 who marched in a parade in the Foroba in October, 1897. But the proportion of bolas was undoubtedly such higher for those troops that were not under Samori's direct control. It does not appear that the 3,500 men equipped with modern rifles who fought back the French at Dwe' in 1898 had been trained in the European way, as the pursuit to the walls of Touba was specifically left to Sasori's elite "Tirailleurs." The strength of the assaults, launched each day at dawn put Lartigue in such difficulty.

These elite troops displayed pride and esprit de corps following the example of the Dabadugu sofas. They resented the fact that they fought whites exclusively, which caused heavy casualties and did not give them the opportunity to loot. In spite of the Alamamy's generosity, these men did not enrich themselves and were frustrated.

In 1896 Ngolo was granted, as a favor, a transfer to the Dabadugu sofas in order to fight tribal enemies in the West, with the obvious purpose of increasing his wealth.

This great effort of organization, armament and modernization was noteworthy in its results. It allowed Sasori to prolong the life of the empire by about 10 years. It explains the paradox the the Alamamy's army, although reduced in size after 1890-92, was never more powerful and effecient than during the last years when east Sofas were trained in European fashion. Monteil's defeat in 1895, Henderson and Braulot's catastrophies in 1897, and the final siege of Kong during which the French garrison was almost destroyed, and finally the Dwe' affair during which Lartigue was clearly defeated, all demonstrate that the Alamamy's army remained formidable, Samori built a force that could fight, if not ultimately defeat, the Europeans.

These remarkable results, however, could not change the inevitable outcome of the confrontation. At no time could Sasori seriously think of attacking the French and permanently forcing thee out of his territory. His greatest ambition was to discourage thee so as to be given the longest reprieve possible. He was, in the end, powerless before the gigantic forces which swept through West Africa. The economic and military resources of the Samorian Empire simply could not match those of colonial France. Satori's fate was already sealed, and he could only postpone the inevitable outcome.

Part 3 of Dirk deRoos' examination of Samori describes the campaigns and battles fought between the Alamamy and the French colonial forces. Watch for the conclusion of 'Un Personagge Nefaste' in the next issue of SAVAGE & SOLDIER!

Un Personage Nefaste: Part 2 French Wars in W. Africa Against the Empire of Samori Toure 1881-1898

Un Personage Nefaste: Part 3 [v19n3]

Back to Table of Contents -- Savage and Soldier Vol. XIX No. 2

Back to Savage and Soldier List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 1987 by Milton Soong.

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com