Against the Empire of Samori Toure 1881-1898

Against the Empire of Samori Toure 1881-1898

VI. Confrontation and War

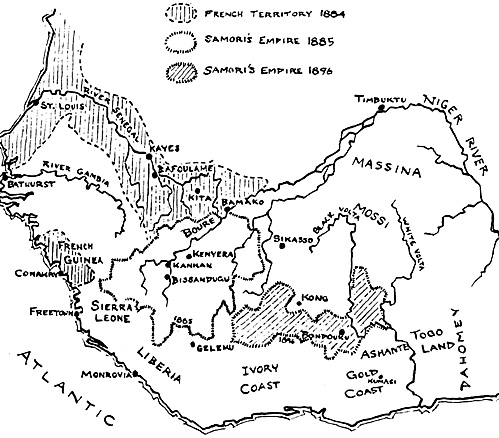

Confrontation and eventual war between Samori and the French were brewing for a number of years before either party was really aware of the threat from the other.

In 1880, Captain Joseph Gallieni, future Marechal de France and eventual hero of the Marne, was leading the surveying party for the French Trans-Sahara and Sudan Railroad. Gallieni was ambushed and attacked at Dio. He lost all of the party's baggage, suffered heavy casualties and barely escaped with his own life. The railroad was brought to a halt.

At the time, this mithief was blamed an the Bambara tribe, but in retrospect it seems sore likely to have been it least instigated by Samori. Much of the turmoil witnessed by the French in West Africa during the early 1880's was certainly the result of the chain reaction set in motion by the explosive growth of the Samorian Empire, but it was not until 1882 that the French first met their great adversary.

In that year the French commander at Kita, near the Niger River, became increasingly aware of an unknown force pushing north towards his isolated outpost. Lt. Colonel Gustave Borgnis-Desbardes, the new French military commandant for the Sudan, listened to the concerns of his subordinate and decided upon an aggressive course of action. Desbordes had been languishing in his post for a year and apparently relished this opportunity to rattle his sabre. His tour of duty had been luckless so far. Yellow fever epidemics had brought the machinery of government to total chaos, with records lost in repeated flights from epidemics, and the precious trans-Sudan railroad consisted of just four kilometers of track. Another route to glory was needed.

A native officer of Spahis, Lt. Alakimessa, was sent as an emissary to Sasori. Alakamessa must have been a classic of his type. Courageous, brash and proud, he demanded to know Sasori's 'intentions' and apparently suggested somewhat too forcefully that Sasori get back on his own side of the Niger. Absolute monarchs expect a bit more deference. Alakamessa was imprisoned and destined for execution. But this lieutenant of Spahis was not so easily silenced.

Somehow he escaped from the clutches of the Alamamy and struggled on foot back to Kita. The alarm was sounded, French honor must be avenged (it was a nice diversion from other problems). Desbordes organized an expedition which found a force of sofas besieging the native town of Keniera. The French drove off the Sasorian troops and Desbordes found what he was looking for; a 'coup de fusil,' a feat of arms. Seventeen years of war had begun.

In April of 1883, Samori struck back. His

sofas attacked the French fort at Bamako. The

French claimed a victory, but Samori had made his

point. He could and would strike the French in

their own territory if he wished. Desbordes led

out another expeditionary force into Samori's

country along the left bank of the Niger. After

much skirmishing and no results, Desbordes

returned to Bamako.

In April of 1883, Samori struck back. His

sofas attacked the French fort at Bamako. The

French claimed a victory, but Samori had made his

point. He could and would strike the French in

their own territory if he wished. Desbordes led

out another expeditionary force into Samori's

country along the left bank of the Niger. After

much skirmishing and no results, Desbordes

returned to Bamako.

But the administrative chaos in Senegal and the French Sudan made Desbordes cautious. He had his 'victories' and didn't want to push his luck with a formidable foe like Sasori.

It was decided that a 'flanking' manoeuver was better than direct confrontation. A force would be sent to Timbuctu complete with a gunboat on the Niger to contain Samori's northward push, The gunboat Niger was built and carried overland in pieces to Bamako. Problems, however, befell the gunboat scheme. Captain Froger, who was to command her, fell ill with fever and, when the Niger was assembled, it was discovered that she didn't float. It took two years to fix the leaks.

A bigger problem involving gunboats was simultaneously occurring at the other end of the Niger. British gunboats shelled the towns of Abo and Idah for cooperating too closely with the French. Now the French saw a conspiracy. Samori must be in league with the perfidious British.

Caution might have been in order. French military prestige and self-confidence was low following a scandalous defeat and retreat for the French at Lang-Son in Indo-China. Another French defeat anywhere would cost the responsible commanding officer his career. Samori was an obviously powerful but largely unknown enemy in an area where the British were making Imperial noises. But in the Sudan, the French were never cautious. When the British declared their protectorate over the 'Niger Districts' in 1985, the French needed no further excuse.

Desbardes had meanwhile been replaced by Major Combes, another 'Officier Soudanais' anxious to make his reputation. Combes convinced the civilian Governor of the Sudan that an expedition was needed to punish a local troublemaker named Ahmadu. When the expedition was ready, Combes ignored Ahmadu and marched against Samori. The Governor was aghast but Combes was gone.

Combes built his main stronghold for the war he intended to wage in Samori's country at a place called Niagassola, with a smaller, more isolated fort at Nafadie. Both forts were a mistake. Nafadie was soon cut off and besieged. It took Combes' full force from Niagassola to raise the siege and even then Nafadie was barely rescued. Surrounded in enemy country by hordes of Samori's troops (too many of whom seemed disconcertingly well-trained), Combes' force had to execute a fighting retreat to the main base. There the rainy season brought French action to a standstill and Niagassola was in turn invested by Samori.

With the main French force locked up, Samori struck at will deep into French territory all the way to the colonial center at Bafoulabe. The French Governor saw the whole thing is a 'disaster of incalculable proportions.'

With typical brass, the military's reaction was to stress the need to punish Samori, and declare French 'influence' over both banks of the Niger. The only thing needed to bring peace, argued the 'Officiers Soudanais', was a little freer hand for thee and a few more troops. The Marines got both, and in early 1866 went after the Alamamy again.

A new commandant, Lt.-Col. Frey was in place and with the largest French force yet assembled in West Africa, he felt sure of easy success. 'Easy' it was not to be.

Samori's defeat of Combes had cost hismdearly in lost equipment and heavy casualties among his trained sofas who had borne the brunt of Samorian casualties. But the Alamamy was also confident, too much so as it developed. For the first and last time, Samori underestimated the French. In a series of reckless set-piece battles, Samori attacked the French in the Bakhoy Valley. Here he learned a bloody lesson about the power of artillery, paid for by the loss of most of his best troops. When it was over, his army was largely destroyed. The French also suffered heavy casualties, but because of 'records lost due to yellow fever epidemic', exact details of French losses were covered up.

At this moment, a curious thing happened. Frey did not deliver the 'coup de grace.' He deliberately let Samori escape. Perhaps the only good enemy in the region was too valuable a commodity to destroy.

At any rate, a treaty came to pass. Samori seemed to meekly accept French 'protection' and agreed to become a 'friend and ally in all matters requested' by the French. It is now obvious that he was buying time. Over the next few years, he armed and trained the hard cadre of sofas that repeatedly defeated the French until 1898.

From 1886 until 1888, Joseph Gallieni ran the French military in the Sudan with an iron hand. One by one he eliminated with a particularly efficient ruthlessness all those who questioned France's absolute right to rule. Samori remained largely quiet, but he could not escape Gallieni's anger. Behind every revolt anywhere in the French Sudan, Gallieni saw (perhaps correctly) the hand of Samori. Gallienei picked Maj. Louis Archinard as his successor in 1888 for the specific purpose of destroying Samori.

The need to destroy the Alasasy was accentuated by the report of Capt. Louis-Gustave Binger. Binger had toured the Niger and Sudan regions on an unofficial 'diplomatic" mission in 1888. He had visited Samori's capital at Bissandugu and was disturbed by the warlike efficiency he saw there. Binger envisioned a great French colony stretching all the way to the sources of the Nile. As a potential ally of the British and a powerful force in West Africa, Samori blocked that dream. He had to be eliminated.

That view was seconded by Lt.

Marchand (later of Fashoda fame) who had at the

same time visited the Tokolors (neighbors of

Samori) and believed that they would eventually

unite with the Alamamy to drive out the French.

That view was seconded by Lt.

Marchand (later of Fashoda fame) who had at the

same time visited the Tokolors (neighbors of

Samori) and believed that they would eventually

unite with the Alamamy to drive out the French.

Archinard, only recently a Captain of Artillery in Indo-China, saw that this was his main chance. He took it and didn't wait for such of an excuse.

In 1899, Archinard claimed knowledge of secret documents revealing a conspiracy against the French led by Samori. On his own initiative, he demanded the withdrawal of Samorian forces from their town of Tankisso. When he received no reply, he marched out and took Tankisso. Then explaining to the Governor that he needed to provision some outlying posts, Archinard disappeared into the Sudan with a strong force.

His written orders forbid an attack on Samori. But nonetheless, an April 9, 1891, he attacked without warning and burned Samori's capital. The Alamamy not surprisingly considered his treaty with the French at an end. The Governor was apoplectic. Archinard treated the whole furor with sovereign indifference. Samori, said Archinard was an enemy in league with the British. As a soldier, it as his sole mission to destroy such enemies. His actions brought his a colonelcy and a transfer.

His successor, Gustave Humbert, continued the war with a strong mobile column of 3,000 porters and 1,300 troops, including Senegalese Spahis, Marine Infantry and Artillery, Tirailleurs, and mounted companies of the Legion.

But Samori's defeats in the Bakhoy Valley in 1886 and the recent destruction of his great capital at Bissandugu had taught his two lessons. He avoided set-piece battles on terrain favorable to the French, and abandoned the defense of geography. Henceforth, his was a guerilla war with a mobile 'empire', moving as the Alamamy moved.

Samori led Huebert into the lake and marsh areas near Diasanko. He built elaborate earth and stone breastworks with dikes and canals cut to flood specific spots. As the French attacked, Samori moved to new previously prepared strongpoints while units of sofas hit the flanks and rear of the French. His men manoeuvered like professionals, fired in salvoes and marched and counter-marched to bugle calls. His elaborate trench system brings to mind the tactics of WWI.

Although the individual sofa was armed as well as his opponents, without any significant artillery (Samori did use several captured howitzers), the Samorian forces could never really stop the French. But the Alamamy made them buy each advance with blood. If his tactics were good, Samori's strategy was better. He relied on his favorite "pincer" strategy, keeping field armies available on the flanks as his main force lured the advancing French into a tightening noose. Huebert was unequivocably defeated.

The retreat from Diamanko across the wasteland left by Samori was a nightmare. Without water or supplies and constantly attacked by the jubilant and victorious sofas, only the toughest and most disciplined troops could have survived. The strain of the unexpected disaster begin to affect the French commander's sanity. Upon re-entry to French territory, Huebert was replaced by Archinard (and Combes) and returned to France a bitter and broken man, his career ended.

Samori's defeat of Huebert was part of a moving 'retreat' to the south and east that the Alamamy pursued for the next seven years. As the French advanced, Samori moved out, taking with his over 100,000 of his people. A whole culture was constantly on the move, each individual part of a scorched-earth policy and a war of attrition. Samori's only supplies came through what he could capture or smuggle in from the coasts. As the French sealed off the Libein frontier in the west, the Alamamy edged towards Dahomey and Ashanti as the remaining sources of supplies and ammunition.

Samori's survival and the threat he posed to French domination of the region caused the implementation of a grand strategy for West Africa. France mobilized all of her colonial troops in West Africa, the Sudan and the Congo for one giant encircling movesent that was to catch and crush the Alamamy.

An expeditionary force under the mulatto

Marine officer, Colonel Dodds, was sent into

Dahomey in 1892. The French had other reasons to

want to deal with Dahomey, but the primary

strategic goal was to cut off another of

Samori's coastal supply sources. It seems

paradoxical that this campaign is relatively

well-known while the greater events of which it

was merely a 'side show" are almost forgotten.

An expeditionary force under the mulatto

Marine officer, Colonel Dodds, was sent into

Dahomey in 1892. The French had other reasons to

want to deal with Dahomey, but the primary

strategic goal was to cut off another of

Samori's coastal supply sources. It seems

paradoxical that this campaign is relatively

well-known while the greater events of which it

was merely a 'side show" are almost forgotten.

While Dodds blocked Samori from the South, Archinard and his subordinate Combes harassed Samori as he retreated to the east. Archinard determined that the Alamamy's alleged supply route from the British colony of Sierra Leone also had to be severed.

In 1889, after both had declared "protectorates" over contiguous areas, Britain and France had reached a gentleman's agreement to survey and mark the frontiers. But the gentlemen soon quarrelled. The French surveyors, angered over British smugness, walked off the job, and the British were left to complete the boundary survey alone. Now Archinard found that Samorian forces were operating on the British side of the Sierra Leone frontier near a village called Erisakono.

For Archinard, the solution was obvious. He would invade the British colony, seize Erisakono, and stop all caravans saving in or out of the British colony. When this was proposed to the French Governor, the poor man was bug-eyed. He ordered Archinard to do no such thing. But the Commandant was not to be put off by such bureaucratic hesitancy. In 1893, he and Combes 'invaded' Sierra Leone, seized the village in question, blockaded trade routes and chased out the British. Shots were fired between British and French native troops. Commanders threatened war, reprisals and counter-reprisals.

Britain protested and a major international crisis seemed headed towards war, but cooler heads prevailed. Britain didn't want a war over a cluster of mud huts an some vague frontier. Archinard got to keep Erisakano. His rashness, however, was too such for even the sternest hawks in Paris. In 1893 Archinard was recalled to Paris where it would be a little harder for his to start his own war.

His replacement was Etienne Bonnier. Late in the year, Bonnier proceeded with the northern part of the pincers against Samori. The new commandant moved out in two columns. Major Joffre (who was to command French armies in WWI) reconnoitered to the northeast in preparation for seizure of the town of Bougouni. There, Bonnier split his forces. Major Richard took a column south to Nionscooridugu looking for Saaari. Bonnier was to move northeast by land and via the Niger with a flotilla of gunboats and transport barges. Bonnier, however, had other plans. Despite clear orders from the Governor, Bannier had decided to march to the edge of the Sahara and conquer Timbuctu!

On the afternoon of December 31, 1893, the Governor was to arrive to wish the Commandant well as he set off, supposedly in search of Samori. Knowing this, Bannier scurried off with his column that earning leaving the Governor in his dust.

The tiny fleet of two gunboats and numerous transport barges under Lt. Boiteux was to support Bonnier's advance along the Niger. But catching wind of Bonnier's scheme, Lt. Boiteux abandoned Bonnier and began his own dash upriver towards Timbuctu.

Orders reached Bonnier from the Governor directing his to stop, but the Commandant lied and responded that he was not advancing but merely stopping an attack. According to Bonnier, 'There is no reason for alarm...this is not a new conquest but ... simply an extension of our influence. It will not involve any additional expenditure.'

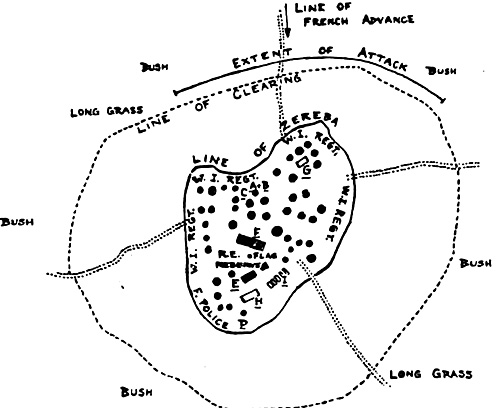

On January 10, 1894, Bonnier reached Timbuctu. Four days later, after skirmishes with Tuareg bands, Bannier camped at Goundam (just abandoned by the Tuaregs) with his advance guard of slightly more than one company of tiraileurs. No patrols were sent out and few pickets posted.

The Tuaregs were intimately familiar with the terrain. That night, they attacked the sleeping camp. By stampeding cattle (captured earlier that day by the French), the camp was put into chaos. The French were annihilated. In the carnage, Commandant Bonnier, ten officers, two European NCOs, the native interpreter and 70 tirailleurs were killed. The few survivors brought word of the disaster back to Bougani. Boiteux, by the way, had the common sense to proceed fullsteam back down the Niger before he, too, fell prey to the Tuaregs.

The extreme eastern edge of the great encirclement

didn't fare such better. In 1894, Commandant Monteil had

been sent to the Congo with a force of 300 tirailleurs with

orders to march to Fashoda (a task later performed by Maj.

Marchand), seize the Nile at that point, and confront the

British. His orders were changed and his 300 troops became

the eastern blocking force against Samori. These orders

interestingly enough directed his to defeat but not to destroy

the Alamamy's army. As it turned out, that was not a problem.

The extreme eastern edge of the great encirclement

didn't fare such better. In 1894, Commandant Monteil had

been sent to the Congo with a force of 300 tirailleurs with

orders to march to Fashoda (a task later performed by Maj.

Marchand), seize the Nile at that point, and confront the

British. His orders were changed and his 300 troops became

the eastern blocking force against Samori. These orders

interestingly enough directed his to defeat but not to destroy

the Alamamy's army. As it turned out, that was not a problem.

Attacked by the elite of Samori's forces, Monteil was overwhelmed and beaten. His pleas for assistance were ignored while 3,000 French troops sat idly by in the Sudan. In the end, Monteil's force lost cohesion and simply disintegrated. The survivors sought refuge in German Togoland. Samori continued his relentless drive towards the Ivory Coast.

In the French colony, panic began to reign. Captain Marchand reported that Samori's advance troops were in the colony by January 1894. Binger, now Governor of the Ivory Coast, stated bluntly that the survival of the colony depended on the defeat of Samori.

The next two years were a time of great confusion and fear for the French. Samori continued to defeat and elude them in fight after fight. Unsure of which direction the mobile "empire' would next take the French often chased ghosts.

French troops intruded into Liberia in 1894 looking for Samori, and when the French commanding officer was killed, news of the disaster was concealed from French authorities.

In February of 1894, French troops 'mistakingly'

attacked the camp of British forces near Waima.

In February of 1894, French troops 'mistakingly'

attacked the camp of British forces near Waima.

French Lt. Maritz was killed and the British lost three European officers and one NCO. There were many casualties among the native troops on both sides. The French uncharacteristically apologized, saying that they thought the British were Samorian regulars.

This may hive led the French to half-heartedly propose a joint Franco-British expedition to end Samori's threat. The British declined and so the French were not disappointed when, in 1897, a well-armed British column of Hausa Gold Coast Constabulary were attacked and annihilated by Samori's regulars. The political officer was killed, the commanding officer, Major Henderson, was captured and paraded before the Alamamy, and ammunition, maxim guns and artillery fell into Samori's hands.

At about the same time, a small French force under Captain Braulot was attempting to locate and negotiate with Samori. Finding instead one of the Alamamy's generals, while under a flag of truce, the party was set upon and massacred. This ended any thoughts that the French may have had favoring a negotiated peace.

To the north, the 'pincers' strategy also came to an end in 1997 when a troop of Spahis at Rhergo, out looking for Samorian forces, was wiped out to the last man by Hoggar Tuaregs. It was obvious that grind strategies over vast and hostile areas with limited numbers of troops were doomed to failure.

The new French military commander in the Sudan, Commandant Caudrelier, determined in October 1897 to mass the 4,000 troops available to his and just go straight for Samori, attacking and pushing continually. Fancy strategies were abandoned, increasing crises with the British added a sense of urgency to the new tactics. Samori, however, was still very dangerous, repeatedly beating the French as they moved towards his.

But the end was probably inevitable. Exhausted by nearly 17 years of war, hemmed in by a powerful ring of enemies and pounded by artillery, Samori had to break out (but to where?), surrender, or take his vast following over the rugged, jungle-covered Dan Mountains which blocked his retreat deeper into Ivory Coast country. His best troops were dead or out fighting rear-guard actions. He was short of ammunition and without food supplies. It was the rainy season so that the mountains were one vast tangle of swamps and crashing torrents. Lastly, he had 100,000 of his people to take with his. The Alamamy decided to try anyway.

Famine and torrential rains soon broke down all cohesion among the largely civilian Samorian throng. By late September 1898, Samori was deep in the Dan Mountains, continually harassed by numerous small mobile French columns attacking again and again. The Alamamy now had no means left to fight back. Tricked into stopping for peace negotiations, Samori was surprised in his mountain camp by a company of tirailleurs under Captain Gouraud and captured on September 29, 1898. The Samorian Wars were over. France was free to pursue her Pan-African colonial dreams, which were to end all too shortly upon the mud-banks of Fashoda.

At the time of his capture, Samori handed his Muslim prayerbook to a French officer, saying, 'This prayerbook is for you. Allah made you stronger. He abandoned me. I no longer have the need to pray."

Un Personage Nefaste: Part 2 French Wars in W. Africa Against the Empire of Samori Toure 1881-1898

Back to Table of Contents -- Savage and Soldier Vol. XIX No. 3

Back to Savage and Soldier List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Milton Soong.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com