In the early 13th century, the Baltic frontier remained a place where pagan Europeans were prevalent in sharp contrast to the Christianized West. The frontier became a place of conflict between exploitive neighbors desiring to carve out small (and large) holdings and expand outward -- at the expense of anyone in their way.

In the early 13th century, the Baltic frontier remained a place where pagan Europeans were prevalent in sharp contrast to the Christianized West. The frontier became a place of conflict between exploitive neighbors desiring to carve out small (and large) holdings and expand outward -- at the expense of anyone in their way.

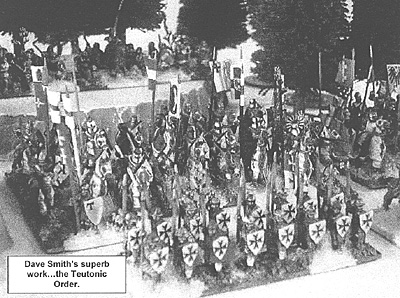

During this period, two major forces came into play in that area. One was the zealous Teutonic Order; mainly German warrior knights who considered it a holy crusade to subdue and vanquish as well as kill the pagan natives and Russians as well for good measure. The other force was the Mongols, who invaded Western Europe in 1223, making it all the way to the gates of Vienna in two short decades before heading back home to the East upon the death of their Great Khan.

Who were the indigenous people inhabiting the lands of the Baltic frontier who were to be victims of the invaders? They spoke various languages, from Baltic in the south to Finnish in the north and, as Adam of Bremen wrote in the 11th century, "They worship serpents and birds and also sacrifice to them live men whom they buy from merchants" (Nicolle 7). They reportedly fought continually, with tribes raiding their neighbors, including raids into Scandinavia and Russia in search of loot, women and slaves (Nicolle, 10).

This was not a hospitable land, with weather making any lengthy campaigns difficult and then only in the brief periods from May-June or August-September as "good" times to fight (France, 198). Winter actually seemed a better time to campaign as the forests were normally impossible to traverse, but frozen rivers, lakes and streams could be crossed easily when iced over (France, 199). Why would anyone want to go into such a violent and inhospitable land?

In essence, the concept of "Drang Nach Osten" was not a 20th century phenomena. Early in the 13th century, King Andrew of Hungary sent to the Master of the Teutonic Order asking for help against the problematic Kuman raiders in Transylvania. Hermann Salza, the Order's master, agreed to lend his military aid for a price: land. It was duly granted. The Order 'pacified' the area by 1225 and began to import colonists from Germany at which time, King Andrew ordered them to leave (Wise, 19), fearing their growing power and influence would become a threat to his own kingdom. The Teutonic Order was not in any condition numbers or prestige wise to fight a national war, so grudgingly complied, putting their military expansionist efforts into another land close at hand, pagan Prussia.

The Order had also been asked by a Polish duke, Conrad of Mozavia, to join him and fight against the Prussians on his borders (Christiansen, 79). This foolishly is reminiscent of the British leader Vortigern asking the Saxons to help him fight the Picts! Needless to say, Hermann of Salza would not allow the situation which had occurred in Transylvania to happen again. The Duke assumed that he would use the Order to protect HIS lands, freeing up his own resources and men to force his Polish neighbors to recognize him as the main power in Poland (Christiansen, 79). But Hermann Salza had demands this time. He wanted a free hand in allowing him and his men to fight who they wanted and to have control over any lands they might 'Christianize'. Conrad duly agreed…to the later regret of many of his countrymen. He saw no problem in letting the Order fight the pagan enemy and if they gained a few miles of forest and swamp, so what?

Hermann of Salza sent a letter to Pope Gregory IX, telling him of his plans to convert the pagans and asking for the Pope's blessing in this endeavor (and also desiring to legitimize his future 'conquests'). Gregory complied, giving his consent as well as a promise of a full indulgence to any Christian willing to fight in Prussia and many did just that (Christiansen, 80).

The Teutonic Order used Prussia as a virtual training ground for war, carving out a kingdom. As David Nicolle wrote, "This was the hour of the birth of a new Germany. The Teutonic Order, engaged in establishing…an independent state, became the interpreter of the national will…" (14). Before WWII, both Adolph Hitler and Josef Stalin would use their respective nationalistic policies; one to applaud the Teutonic Order, the other to vilify it.

Prussia was not the only region in the area that was being 'converted'. Germans had also colonized the border area of Livonia under the auspices of a crusade to convert the pagans of this region to Christianity. This was accomplished due to the efforts of two ambitious bishops, Albert von Buxhoeved and the Bishop of Estonia. They determined in the early 13th century that in order to be successful in such an endeavor they would need help in expanding control into these lands and then defending the new area.

Christianity had been spread by missionaries…with great success throughout the rest of Europe. The missionaries would first go to the tribal leaders and tell them stories…exciting stories of brave men who died for their beliefs in very horrible ways. The pagans would listen and slowly become fascinated by the concepts of personal salvation, sacrifice and an afterlife. Once the tribal leaders had decided to accept Christianity, it was a simple matter for them to demand that their followers do the same.

In the Baltic region, this approach simply did not seem to work. So, the two Bishops established a religious order of warriors called the Sword Brethren in the town of Riga circa 1202 (Christiansen, 76). Getting men to join such a group was not easy. The knights basically had to be 'bought' by Albert as they owed no official allegiance to him, only to God, so he promised them land and power. Some knights did join for other reasons; escape from a boring life, troubles at home, sheer bloodlust and even the idea of doing God's work (Urban 80). With these warriors, Albert did manage to convert and hold onto Livonia -- by force.

The always small numbers of Sword Brethren garrisoned fortresses and trained men in the ways of Western warfare, augmenting their numbers with retainers, 'seasonal' knights, local militia and townsmen, but always keeping an eye on their local 'allies' for any outbreaks of blood feuds (Urban 84). Native light horsemen were also used as scouts and foragers, but were more often interested in rape and pillage than doing God's work (Urban 84).

The Sword Brethren (or 'Swordbrothers'), never numerous, were the leaders of the Livonian Crusade until 1236, when they made a poorly planned raiding expedition into neighboring Samigotia. On their return, they were attacked by Lithuanians (and perhaps Scandinavians) as they crossed the Saule River and were literally cut to pieces, losing 1/2 of the Swordbrothers as they fought encumbered in the water (Nicolle, 14; Urban, 85; Wise 26).

Hermann von Salza immediately wrote to Rome upon hearing of the disaster, asking the Pope to henceforth incorporate the survivors of the Swordbrothers into the Teutonic Order, thereby gaining more land, more power and more fighters for the German order. Lacking representation (only two members of the Swordbrother order were in Rome at the time of the arrival of the petition from von Salza), the Swordbrothers were by Papal order then made part of the Teutonic Order (Urban, 90). Though Hermann von Salza had thought to expand the power and control of the Order, instead he would find his knights spread very thin trying to defend a border stretching from the Polish frontier to Lake Piepus.

Battle of Lake Piepus 1242

Back to Saga # 97 Table of Contents

Back to Saga List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2004 by Terry Gore

This article appears in MagWeb.com (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com