Accuracy

Accuracy

The smoothbore musket is not a very accurate weapon by today's standards. It was said that an individual, aiming at a target the size of a man at a range of 150 yards, had as much chance of hitting the target as he did of hitting the moon. However, from the earliest use of the musket target formations were in close order. The still medieval-like bodies of troops deployed on the battlefield to enhance their melee effectiveness, which was the major method of winning battles. Infantry had to deploy in dense and deep formations to prevent from being run down by the heavily armored cavalry. Musketeers had to stay close to the pikemen for defense against the cavalry. Therefore deploying an army in close order formations was a necessity.

The inaccuracy of the musket was less of a disadvantage, because aiming at a formed body of troops had a reasonably good chance of hitting somebody. It is also easier to control a body of troops in formation than it is in dispersed order, therefore a formed group of musketeers could deliver more shots in a given period of time than an unformed body. During the period from the late 16th century to the early 19th century, the primary method to deliver fast and effective fire was dictated by keeping the musketeers formed.

The accuracy of the musket is partly dictated by the windage, i.e., the difference between the interior barrel diameter and the ball's diameter. The windage also affects the speed of reloading and the muzzle velocity. The greater the windage, the easier it is to ram home the ball into the barrel. This also allows more gas to escape from the barrel without pushing the ball out of the barrel. Therefore less windage will yield a higher muzzle velocity and higher accuracy. The tactics of the time influenced the armies to have more windage to increase the reload speed. More volleys meant more casualties. Accuracy was not considered an important factor by the experts of the period.

Though the accuracy of the smoothbore musket was considered poor, the use of skirmishers during the period to harass the enemy was not uncommon. Typically the skirmishers used the same weapon as the formed troops. Though shots at longer distances were inaccurate, an aimed shot at 50 yards had reasonably good chance to hit an individual target.

Trials

Despite the inaccuracies of the smoothbore musket, studies were made by various nations in the 18th and 19th centuries to determine the effectiveness of a body of musketeers against the enemy. At many of these trials a group of musketeers would aim and shoot at a target the size of a battalion or company and count the number of hits at one or more known ranges. Also there were trials to determine how many volleys could be delivered over a given length of time. Prussian trials in 1810 found that a musketeer could deliver 2 to 2-1/2 rounds per minute, which is comparable to the British rate of fire. However, the Prussian trials also showed that there was a lot of variability in the reloading rate.

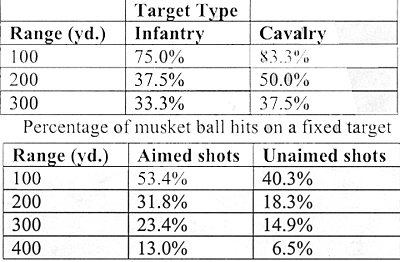

Hanoverian experiments in 1790 showed that when fired at various ranges against a representative target (a placard 6 ft high and up to 50 yd long for infantry, 8 ft 6 in high for cavalry) the following results were achieved at the ranges shown:

Hanoverian experiments in 1790 showed that when fired at various ranges against a representative target (a placard 6 ft high and up to 50 yd long for infantry, 8 ft 6 in high for cavalry) the following results were achieved at the ranges shown:

|

|

Target Type |

|

|

Range (yd.) |

Infantry |

Cavalry |

|

100 |

75.0% |

83.3% |

|

200 |

37.5% |

50.0% |

|

300 |

33.3% |

37.5% |

Percentage of musket ball hits on a fixed target

The weapon used was an infantry musket firing a 3/4-oz ball and the shooters were able to aim each shot. Obviously the cavalry target received more hits because it was a bigger target.

Another experiment described by Mueller (1811) involved the use of aiming versus no aiming. Infantrymen in the aiming group were encouraged to aim their muskets as hunters would instead of just pointing it roughly ahead and pulling the trigger. Each group fired 1,000 rounds against a cavalry target. The results of this experiment are shown below:

Another experiment described by Mueller (1811) involved the use of aiming versus no aiming. Infantrymen in the aiming group were encouraged to aim their muskets as hunters would instead of just pointing it roughly ahead and pulling the trigger. Each group fired 1,000 rounds against a cavalry target. The results of this experiment are shown below:

|

Range (yd.) |

Aimed shots |

Unaimed shots |

|

100 |

53.4% |

40.3% |

|

200 |

31.8% |

18.3% |

|

300 |

23.4% |

14.9% |

|

400 |

13.0% |

6.5% |

Percentage of musket ball hits on a fixed target

These results demonstrate that aimed fire is significantly better than unaimed fire, even for a smoothbore musket, especially more significant at longer ranges. This indicates that skirmishers using aimed fire from long range can actually cause significant casualties. However, skirmishers also tend to shoot less often than formed volley shooters, roughly canceling out the increased benefit of aiming. British infantry of the Napoleonic Wars were taught to aim their volleys. Aimed fire and the excellent British reload training would explain the factors contributing to the renowned British, superior fire discipline.

It must be emphasized that these trial results are for laboratory-like conditions. There was no stress upon the shooters as would be expected on the battlefield. Also the targets are solid placards. Infantry and cavalry are composed of individuals with gaps between them. Therefore, actual battlefield effectiveness would be much less than the above results.

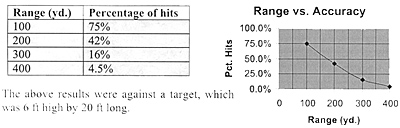

One can make an inference from these data on accuracy versus range to target. It appears that the accuracy is inversely proportional to the distance. In other words, the accuracy at range R is half that of range 2R, or double the range and cause half as many casualties in the range of 50 to 300 yards. Greener (1881) gives the following figures for a percussion musket, which was only marginally better than the flintlock as regards range and accuracy, as follows:

|

Range (yd.) |

Percentage of hits |

|

100 |

75% |

|

200 |

42% |

|

300 |

16% |

|

400 |

4.5% |

The above results were against a target, which was 6 ft high by 20 ft long.

Actual Battlefield Results

At the Battle of Blenheim (1704) the British with five battalions attacked the French fortified positions along a front of 750 yds. The French had approximately 4,000 fusiliers deployed along 900 yds. The French opened fire at 30 yards with a single devastating volley causing 33 percent casualties to the British attacking force. This came to approximately 800 casualties. Therefore 20 percent of the French rounds were effective. If we assume that 15 percent of the French muskets misfired, this gives an effective rate of 23 to 24 percent of those muskets that actually fired.

At the Battle of Fontenoy (1745) five British battalions with a total strength of 2,500 men, less a few hundred men due to French artillery fire, let loose a volley at 30 yards against an attacking force of five French battalions. The British volley caused 600 casualties to the French. This would mean that the British muskets were hitting with an effective rate of 25 percent.

At the Battle of Minden (1759) Hughes estimates that the effectiveness of musketry by both British and French was less than two percent per volley. In this battle the French and British engaged at much longer ranges, 100 to 150 yards. At the Battle of Albuera (1811) a French divisional column attacked the British position. The British muskets averaged a two-percent effectiveness rating at that battle at a range of 100 to 150 yards. However, at the same battle on the French left flank, the average effectiveness was about 5-1/2 percent per volley for both sides. Hughes concluded that at Albuera the actual effectiveness dropped off rapidly with range between 30 and 200 yards. He also stated that smoke on the battlefield often obscured the aim of the shooters, which would lower the effectiveness dramatically. Hughes also concluded that the infantry of the first half of the 18th century are better trained than those of the later 18th and early 19th centuries. If true, then one would expect higher musket effectiveness for the earlier period.

Based on the above historical incidences, wargame rules should incorporate a range attenuation factor, which simulates the effectiveness of the smoothbore musket in battle. The first volley bonus has already been discussed. However, the effectiveness of infantry musketry is also affected by training, discipline, morale, and local conditions (smoke, cover, etc.).

Range of Engagement

Bodies of musketeers generally engaged in firefights at ranges of 100 yards. However, in the early period, it was not unusual to engage at longer ranges. During the 18th century, it was not unusual to fire an initial volley at ranges of less than 50 yards. Firefights between opposing lines of infantry tended to last no more than 15 minutes. At the end of this time one side or the other would give way due to loss of morale. Wargame rules that use a first volley bonus cause a tendency amongst wargmers to withhold their fire until within the most effective range. This tends to simulate actual tactics of the period.

Smoothbore Musketry

Back to Sabretache # 1 Table of Contents

Back to Sabretache List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by Terry Gore

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com