(Editorís Note: This article and the one following it present a good overview of the major long weapons used throughout the timeframe covered by the newsletter. My thanks to Larry for allowing the first article to be re-printed. )

(Editorís Note: This article and the one following it present a good overview of the major long weapons used throughout the timeframe covered by the newsletter. My thanks to Larry for allowing the first article to be re-printed. )

16th cent. Arquebusier from Gush, 1975

Introduction

Many wargame rulesets are designed for the period of the smoothbore musket, for example, English Civil War, Seven Years' War, and the Napoleonic Wars. However, most of these rules do not include information on how the casualty system was devised. This article analyzes the factors related to the smoothbore musket that should be addressed in wargame rules and simulations for this period.

Early Smoothbore Musket

The smoothbore musket was a long-ranged firearm derived from the earlier arquebus (or hackbutt) during the 16th century. The musket was initially heavier than the arquebus, requiring a wooden rest to aim, and had a length of 6 ft compared to the arquebus's 4 ft. Calibers of the weapons varied from 0.50 inch to 0.75 inch. The musket also had a longer range and higher muzzle velocity than the arquebus. The arquebus was preferred by some, because of its easier handling (skirmishers preferred the arquebus) and faster rate of reload (2 or more minutes for the musket versus 1 to 2 minutes for the arquebus). The heavier musket also absorbed more of the recoil at discharge. However, the lower muzzle velocity of the arquebus did not always penetrate armor, which was still worn by pikemen and cavalry. In the Spanish and Imperialist armies, there were bodies of both arquebusiers and musketeers.

The bayonet had not been invented yet. Arquebusiers and musketeers depended on bodies of pikemen to defend themselves from cavalry charges. The musketeers and arquebusiers also carried swords for fighting hand-to-hand. However, their firearms were usually used as clubs in melees.

Both weapons were muzzle loaded and used a match to discharge the weapon. To load the weapon, the shooter would unplug a wooden container called an apostle (because there were 12 of them) from his leather bandoleer. He would then pour a pre-measured amount of loose gunpowder from the apostle into the muzzle of the barrel. Then a lead ball from a sack was placed into the muzzle and rammed home into the chamber with a wooden scouring stick (a.k.a. ramrod). The powder pan on the side of the musket barrel was opened and loose gunpowder from a powder flask was poured into it. A glowing match made from cord soaked in saltpeter was placed in the hammer of the lock. The shooter would aim his weapon. The trigger was pulled forcing the match into the pan igniting the powder. The flash from the pan would travel into the chamber through a hole and ignite the powder. The expansion of gases would force the ball on its way to the intended target.

The powder in the chamber ignited slowly. Too much powder resulted in the ball leaving the muzzle before all of the powder had been ignited. A correct balance between charge size and length of barrel was important to ensure that all of the powder was ignited before the ball left the muzzle of the barrel. The correct relationship between charge size and barrel length maximizes the muzzle velocity of the ball. In general a higher muzzle velocity results in greater range and accuracy, and better penetration into armor.

17th cent. Musketeer from Gush, 1975

Because reloading took a long time elaborate methods were designed to provide a continuous stream of fire against the enemy. Troops were deployed in formations of 6 or more ranks to deliver their shots one rank at a time. After one rank of shooters fired a newly reloaded rank would move in front of the them (fire by introduction) or the most recent shooters would move to the rear and reload (fire by extroduction), exposing a loaded rank.

During the late 16th and early 17th centuries many Protestant armies experimented with lighter muskets that were easier to handle and load. This decreased the reload times down to 2 or less minutes. In some cases the musketeer did not need a musket rest and the lighter muskets still had good armor penetration power. The development of the lighter musket led to the fallout of the arquebus. By this time the usage of armor began to diminish, too.

The Protestant armies, armed with their lighter muskets, experimented with salvo fire. This involved the fire of two or more ranks simultaneously. In the late 16th and early 17th centuries, the Huguenots of France under Henry of Navarre during the French Religious Wars and the Dutch, under Maurice of Nassau, in their war of independence against the Spanish, were the first to use the salvo fire method. Later the Swedes under Gustavus Adolphus used salvo fire very effectively against the Polish and Imperialist armies. A Swedish brigade is reported to have stopped seven Imperialist cavalry charges with salvo fire at the Battle of Breitenfeld (1631) during the Thirty Years' War, proving the effectiveness of the method.

Matchlock Musket - 17th cent. From Gush, 1975

Matchlock Musket - 17th cent. From Gush, 1975

Another major contribution by the Swedes was the adoption of the paper cartridge. A musketeer was equipped with a cartridge box that contained pre-made rounds of powder and ball. The musketeer would grab a paper cartridge from the box, then bite down on the ball and tear the cartridge open. He would pinch off a small amount of powder in the cartridge and pour the remainder into the muzzle of his musket. The remaining powder was poured into the flash pan. The ball was retrieved from his teeth and placed into the muzzle. Then he rammed the ball down the barrel until it was well seated into the chamber. The musketeer then placed the match into the lock, took aim, and discharged his weapon. The Swedish combination of lighter, handier muskets, with paper cartridges, and salvo tactics enabled the Swedes to reload at one-minute intervals.

Flintlocks

In the late 16th century, the firelock was invented. This invention eliminated the glowing match and replaced the match with a flint. The flint struck against steel over the flash pan, emitting sparks to ignite the powder therein.

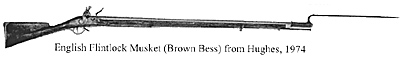

English Flintlock Musket (Brown Bess) from Hughes, 1974

The flintlock decreased the reload time, but was more expensive than the matchlock mechanism. The abundance of gunpowder in the artillery train prohibited the use of burning objects (i.e., a glowing match) in the vicinity and the firelock became the preferred weapon for the artillery train guards. The firelock was also known as a fusil, and this is the origin of the term fusilier. Later the firelock became known as the flintlock. Flintlocks became more popular over time as their cost diminished and reliability improved. By the end of the Malburian wars of the early 18th century, the matchlock was completely replaced by the flintlock. Another advantage of flintlocks over firelocks is formation. Matchlocks require more distance between individuals because of the glowing match and the necessity of moving ranks after each salvo, whereas the flintlock allows a close ordered formation.

Volley Fire

In the late 17th century, the English and Dutch armies adopted volley fire, coinciding with the adoption of the flintlock musket. Volley fire differed from salvo fire. Salvo fire involved the simultaneous fire of entire ranks of the battalion. Volley fire involved the simultaneous discharge of all men in one sub-unit, called a platoon, which was deployed in three ranks. The entire battalion would be divided into 8 or more platoons. Each nation adopted different firing orders of the platoon. One popular method involved the platoons alternating their fire, first from the outside, right then left, and continuing the firing order toward the center of the battalion. This allowed a continuous fire to be presented to the enemy and minimized the obscurity of the target caused by smoke. Also there was no need to exchange ranks as in salvo fire resulting in less confusion in the ranks after discharging the muskets.

All European nations adopted the volley fire method by the end of the Malburian Wars. The Prussians made modifications to the method to allow troops to reload while marching during the War of the Austrian Succession. However, this decreased the accuracy enough that such volleys were ineffectual. The British perfected volley fire to a science during the Napoleonic Wars. A well-trained musketeer of the British army during the early 19th century could reload in 30 seconds or less.

Misfires and Fouling

The smoothbore musket is prone to misfire due to a number of circumstances. The method of loading the musket introduced inaccuracies in the amount of powder used, causing variations in the performance of the weapon. The firing mechanism, with its crude method of priming, was also by no means reliable and misfires occurred frequently. Laurema (1956) states that at the end of the eighteenth century 15 percent of musket shots misfired even in dry conditions. The incidence of misfires must have been appreciably higher in the wet conditions which so many battles were fought in Western Europe. It would therefore seem likely that nearly a quarter of the musket shots misfired.

Gunpowder leaves a residue after igniting inside the chamber of a musket. This residue continues to accumulate during the heat of battle. This increases the reload time and increases the chance for a misfire. Also flints are brittle and can break, requiring replacement. During a battle a battalion will tend to increase its reload time and deliver less shot as the fouling increases over time. Therefore the most effective volley will be the initial volley and the early subsequent volleys. Some wargame rules give a bonus for the first time a unit shoots. Depending on the time scale of the ruleset, this is a valid factor.

Response: Letter to Editor [S#3]

Bayonets

Although the bayonet is not a firearm, after its general introduction, it becomes an integral part of the smoothbore musket. In the 16th and 17th centuries, musketeers sometimes adopted defensive weapons to protect themselves from cavalry. The most portable weapon was the Swedish feather (a.k.a. swine feather). The Swedish feather was a pointed stake and musket rest combination. The stake was planted pointing toward the enemy to act as a defensive obstacle. Gustavus Adolphus's Swedish army used Swedish feathers against the Polish Army, which had a high percentage of cavalry. During the Thirty Years' War, the Swedes did not use Swedish feathers to any great degree, probably because the terrain offered better cover against cavalry and there was less cavalry in Germany than in Poland.

In the latter half of the 17th century, French musketeers started to use plug bayonets. The bayonet literally plugged into the muzzle of the musket. This had the unfortunate side effect of no longer allowing the musket to be neither reloaded nor fired. Later still the ring bayonet was invented. This was a bayonet with a ring to allow it to be attached to the barrel. This allowed the musket to be reloaded and fired while the bayonet was attached. However, during melees the ring bayonet was known to fall loose.

Finally the socket bayonet was invented in the late 17th century. This allowed a bayonet to be securely attached to the barrel of the musket. This also eliminated the need for pikemen to support the musketeers. The last pikemen disappeared from the rolls of the regiments by the end of the Malburian Wars.

Iron Ramrods

The next major invention for the smoothbore musket was the iron ramrod. Prior to the mid-18th century, ramrods were made of wood. A musketeer had to be careful in the heat of battle not to push too hard with his ramrod or risk breakage. The windage, the clearance between the ball and barrel, had to be increased to allow the ball to be seated home. This decreased the accuracy of the musket using the wooden ramrod. Frederick the Great prior to the War of the Austrian Succession (1744-1748) implemented the iron ramrod. This invention helped Frederick's Prussians to increase their overall reload speed as well as accuracy. Other European nations adopted the iron ramrod after the War of the Austrian Succession.

Smoothbore Musketry

Back to Sabretache # 1 Table of Contents

Back to Sabretache List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2003 by Terry Gore

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web. Other articles from military history and related magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com