The US had a numerically small cruiser force before and during World War I. There were several fairly powerful armored cruisers, including the so-called “Big Ten” which originally had state names, indicating their comparative power. These ships were suitable for supplementing the battle line of pre-dreadnoughts or showing the flag in places where a powerful ship was wanted for psychological reasons. There were a number of smaller vessels that were known as “peace cruisers”; these were actually powerful gunboats which were also used for diplomatic and flag-showing missions.

A major weakness of the US fleet was the lack of fast scout cruisers. The only examples in US service were the three Chester-class vessels, which were clearly behind British standards by 1917 and had been built in part as powerplant experiments. This lack was not remedied until the post-WW I appearance of the Omaha class. They were large for their mission and obsolete in layout, and were built in inadequate numbers. In service they served primarily to provide direct support for the battle fleet, rather than in their intended scout role.

The older Spanish American War cruisers of the New Steel Navy had been scrapped or converted to secondary roles by the US declaration of war in 1917. Of the more modern Spanish-American War veteran ships, many had been wholly or partly rearmed to take advantage of the transition to more powerful gun propellants.

The most significant examples were New York, practically rebuilt between 1907-1909 and which became Saratoga in 1911 and was renamed again to Rochester in 1917; and New Orleans and Albany, which were rearmed with American weapons in place of their original British guns. The gunnery revolution of 1905-1910 affected US cruisers as well, with the Big Ten receiving cage foremasts like their pre-dreadnought cousins after the return of the Great White Fleet, indicating the fitting of high spotters and rangefinders providing information to first generation fire control systems.

Older cruisers also sprouted rangefinders, but without the provision of the high elevation spotters. While the war was going on, but before the US was involved, two cruisers were lost to accidents: In 1916 Memphis was washed ashore by a tidal wave in San Domingo, and in early 1917 Milwaukee went aground in California trying to pull off a grounded submarine (the sub was eventually salvaged, but the cruiser was caught fast and had to be scrapped).

When the US declared war in April 1917, most cruisers on foreign stations were recalled home and refitted. The Big Ten got a full director fitting, while the other ships received minor improvements. All of the ships lost many of the smaller guns from their secondary and light batteries. The US had quickly followed the British practice of arming merchant ships to discourage attacks by surfaced U-boats. However, US gun factories would have been totally overwhelmed trying to create new weapons for US merchant ships, especially with Army’s expansion (the US Army used mostly French-built artillery pieces during its time in Europe).

Thus, some or all of the secondary and light guns on many second-line US ships, intended for defense against torpedo boats, were removed for installation on merchants. These ships were unlikely to meet an enemy fleet with torpedo boats, and North Atlantic experience quickly demonstrated that hull-mounted guns were useless above sea state 3 in any case.

The 7 inch guns of the Connecticut class were adapted for towed ground mounts and provided to Army artillery units sent to Europe. Olympia and the three scout cruisers were rearmed, and one of the scouts even totally re-engined - the reciprocating-engine ship was not given turbines; rather one of the turbine ships given a better turbine plant! The Denvers, the best of the peace cruisers, lost a gun on each side, and served as makeshift light cruiser convoy escorts.

Many US cruisers and even some US pre-dreadnought battleships escorted convoys carrying troops and supplies to Europe when they were started in the summer of 1917, a few months after the US entered WW I. The command that provided the anti-raider escorts was called the North Atlantic Cruiser Force. Even with many of their smaller guns removed, the cruiser’s main batteries were powerful enough to give pause to any surface raider, or to discourage U-boats from using their guns.

The following US ships operated at some time or other under this command, with the number of transatlantic convoys escorted listed in parentheses after each ship’s name:

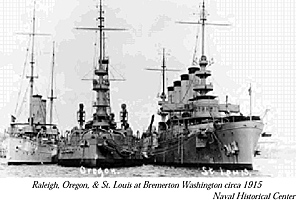

Raleigh, Oregon, and St. Louis at Bremerton, Washington circa 1915 (Naval Historical Center)

Raleigh, Oregon, and St. Louis at Bremerton, Washington circa 1915 (Naval Historical Center)

- Battleships: South Carolina (2), Michigan (1), New Hampshire (1), Kansas (1), Louisiana (2), Nebraska (3), Georgia (2), Virginia (1)

Armored Cruisers: Montana (7), Huntington (1), Pueblo (2), San Diego (3), Frederick (1), South Dakota (3), Charleston (5), St. Louis (7)

Old cruisers: Rochester (5), Olympia (1), New Orleans (9), Albany (11), Columbia (8), Minneapolis (5)

Peace Cruisers: Chattanooga (11), Cleveland (6), Denver (8), Des Moines (9), Galveston (6), Tacoma (8)

South Carolina and Michigan operated with the pre-dreadnoughts because of their slower speed; interestingly, each had a propeller fall off on North Atlantic crossings, the cause never being determined.

The numbers above indicate how troop convoys were generally escorted by a battleship or at least an armored cruiser, and a smaller cruiser as well, while most of the smaller cruisers also escorted regular cargo convoys. Cruisers that did not participate in the North Atlantic Cruiser Force were generally assigned to the East Coast, the Caribbean Force, or even continued to show the flag (and watch for disguised raiders and blockade runners) in Central and South American waters.

In addition, the scout cruisers Chester and Birmingham went to Gibraltar and escorted convoys from Gibraltar to Britain and France and back, while Salem took two convoys of submarine chasers bound for the Mediterranean as far as the Azores, then returned to Key West where she was the flagship for the submarine chasers operating in the Caribbean.

The heavy escort ships went as far east as fuel permitted, then returned to a US or Canadian port without refueling, except that they were not to go beyond meeting destroyers which would come out to bring the convoy into England, or in any case beyond 15° West longitude.

An exception was Dewey’s Manila Bay flagship Olympia. She went all the way to England with her convoy, and then was part of the Allied expedition to North Russia after the Russian Revolution.

San Diego was sunk by a U-boat-laid mine off New York in 1918, the only major US warship lost in the Great War due to enemy action. Some of the cruisers served postwar in the Mediterranean, upholding American and Allied interests after the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and in the revolution in Turkey.

Others went to Siberia to support the Intervention Force there during the Russian Civil War. Tacoma of the Denver class was lost on a reef near Vera Cruz, Mexico in a storm in 1924. None of the US WW I cruiser force survived to serve during WW II in anything but a moored training role, but the hulk of the Rochester, decommissioned in the Philippines in 1933, was sunk as a blockship in Manila Bay in December 1941 to deny her use to the Japanese. The wreck of San Diego is a popular advanced-skills dive site off Fire Island.

Olympia was totally stripped by WW II. She now has fake 8 inch turrets, and a battery of 5/51 guns removed from the battleship Colorado installed to restore her to some semblance of her Manila Bay appearance (but in a peacetime white and buff paint job). Moored in Philadelphia, she is the only surviving US cruiser of this era still afloat.

The Convoys

Troop ships usually sailed in convoy throughout the war, unlike freighters, but the submarine crisis of 1917 convinced the British Admiralty to revert to the “obsolete” tactic of convoy with great success (helped, in truth, because the number of escort vessels built had finally become sufficient). As in WW II, fast ocean liners might sail independently, relying on their speed to avoid attack, but slower passenger ships sailed in convoy. The following rules helped determine the positions of ships in a convoy:

- 1) The heavy ships were not placed immediately behind the light ones since they took longer to lose way and would close up on the ship ahead, perhaps dangerously, if the convoy had to slow.

2) Vessels carrying special cargoes or passengers were placed in better-protected positions in the convoy.

3) The best-armed ships were in the outside columns.

4) Ships with horses aboard were placed at the head of columns so that they would not have to follow zig-zags exactly and could take easy courses in case of heavy weather (the total number of horses transported from the US to Europe is unknown, but the total for October -November 1918 sailings was 15,000, and the US Army operated at least 25 ships as horse transports!)

5) The Convoy Commodore’s flag was, if possible, a ship with a convoy-experienced master and with good communications equipment.

6) If the convoy was to be split to proceed to different destinations, this was taken into account so that groups of ships might depart together still in formation.

7) There was a rule to limit the number of transports in convoy to no more than 14, as of 1918. A port is a choke point - not a narrow passage, in the sense the term was used in the 1970s and 1980s, but a place where traffic converges. Accordingly, strong local escorts were provided around ports.

Convoy HX50

It is instructive to examine the local escorts provided to convoy HX 50 in late September 1918: Two converted yachts, one with a kite balloon to lead the convoy out of harbor; an additional destroyer; and six submarine chasers. The regular harbor entrance patrol consisted of two more converted yachts, one with a kite balloon, and a destroyer with a kite balloon, and in addition one blimp and three seaplanes were to patrol in the vicinity of the convoy. The lead yacht was to leave the convoy at dark; the subchasers at the 100 fathom curve, and the additional destroyer the next morning. The second converted yacht was not a direct escort, but instead patrolled the intended path of the convoy from dawn until its departure at 1500 hours local time, listening for U-boats.

HX 50 is an interesting convoy -- very late in the war, with a strong escort, interesting complications to its voyage -- and also, complete data is available on its composition. Thus, HX 50 is used as the basis for a hypothetical scenario assuming a possible attack on a 1918 convoy, demonstrating the role of the North Atlantic Cruiser Force, and making an interesting contrast with the Colonial Convoy scenario provided in Fear God & Dread Nought.

Bonus Data:

A surprisingly significant US contribution to the naval side of the Great War was the 110-foot subchaser. Over 400 were built, with 100 being transferred to France. These were wooden-hulled craft, built very quickly, with 3 engines and shafts. A more powerful engine with a two-shaft installation was the originally planned, but this engine could not be mass-produced in the numbers required. Preliminary design began soon after Germany reverted to unrestricted submarine warfare in January 1917. The first contracts were let on 3 April 1917 (three days before the US declaration of war!) and the first boat was commissioned in August 1917.

The first few boats carried 6-pdrs, but most of the rest switched to the 3”/ 23. Once it became available, a Y-gun depth charge thrower was fitted on the foundation intended for the second gun aft, and DC racks were worked in astern. The engine change and depth charge weights overloaded the boats in terms of speed, but not seaworthiness; they lost a knot compared to the design speed, but many actually crossed the Atlantic to Europe under their own power.

By Armistice Day, there were about 50 at Plymouth, UK, 30 at Corfu supporting the Otranto Barrage, 18 at Gibraltar, 12 at Brest, 14 in the Azores, and 10 at Murmansk. Many of the Corfu boats provided inshore patrol during the Allied bombardment of Durazzo in October 1918. Mediterranean tactics involved boats sailing line abreast in groups of three to assist in triangulating submarine contacts. Boats based in US waters patrolled the east coast and Caribbean, provided local escort for departing and arriving convoys, and even escorted southern-track convoys part way to Bermuda.

Twelve survived in USN service in WW II; others served with the Coast Guard in the 1920s and 30s.

More WWI North Atlantic Cruiser Force

BT

Back to The Naval Sitrep #21 Table of Contents

Back to Naval Sitrep List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2001 by Larry Bond and Clash of Arms.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

Other military history and related articles are available at http://www.magweb.com