Klenau's Corps

The 4th Austrian Armeeabteilung was, during the night of 13/14 October, so exhausted from its strenuous march of the previous day that it collapsed near Threna without establishing itself on the important terrain features of the battlefield. The advanced guard had stood idly by and allowed the French to occupy the point of the University Forest and the village of Gross-Posna.

At 6:00 a.m., Klenau answered Wittgenstein's note of 13 October. This note requested that he and his Armeeabteilung attack the French as soon as the cannon fire from the left wing was heard. Klenau sent Wittgenstein word that he wished to be excluded from the beginning of the attack because of the condition of his forces. General Pahlen, however, had been assured that Klenau would cooperate with the attack.

At the same time, Schwarzenberg, commander of the Army of Bohemia, sent out a corrected note acknowledging Klenau's situation. The proposed attack would be difficult, because of the isolated location of the his forces, the bad communications and the limited support he could expect. In addition, he noted there was a small chance of a counter-attack by the French forces gathered near Leipzig.

For Klenau to ignore written orders

without receiving a reprimand later

indicates some other communication occurred.

According to Klenau's statements, around 7:00 a.m., two notes arrived. The first was an order from allied headquarters. It directed the 4th Armeeabteilung to move to Borna around 4:00 a.m. The second message was from Wittgenstein requesting essentially the same thing.

Yet Klenau did not move. It cannot be assumed that Klenau totally ignored these orders, and, on the other hand, there is not the least indication to be found in any documents that he made any preparation for the departure to Borna. It is certain that Klenau's behavior on 14 October was influenced by other factors. Circumstantial evidence suggests that Baron Toll may have intervened. For Klenau to ignore written orders without receiving a reprimand later indicates some other communication occurred. It is, therefore, very probable that in the morning Toll either personally carried word to Klenau, or he sent a general staff officer ordering the 4th Armeeabteilung to attack Liebertwolkwitz. Only in light of this can Klenau's hesitation be understood. Otherwise the order to march on towards Borna would certainly have been carried out.

Wittgenstein's short order "The enemy retires..." was received by Klenau around 9:00 a.m. Opposite the 4th Armeeabteilung the French stood quietly, making no effort to advance. Liebertwolkwitz was entrenched and strongly held by the French. On the heights to the south of Liebertwolkwitz, by the windmill, stood about 100 cavalry. To the west was a force of 10,000 to 12,000 French deployed in battle order. Twenty guns stood on the Galgenberg Heights.

The slope south of Liebertwolkwitz was covered with swarms of French skirmishers. It is understandable why Klenau showed so little inclination to attack the exceedingly strong position by Liebertwolkwitz. Especially since the Allied column on his left, which was supposed to be advancing through Stormthal, was still not present. Also, the report from General Pahlen arrived stating that he had not yet begun to comply with Wittgenstein's order to advance towards Stormthal.

The cannon fire from Wittgenstein's force grew louder and Klenau did not appear. Toll sent a direct order from Schwarzenberg to Klenau, directing he attack Liebertwolkwitz and the heights behind it.

This finally motivated Klenau, who, around 10:00 a.m., ordered preparations made for the attack. He then issued orders for part of his corps to undertake a limited attack; only his cavalry and the advanced guard under Mohr were ordered forward. Splenyi's Brigade was to follow behind as a reserve. The other troops remained in their positions.

Three times the French tried to retake the village,

but the two Austrian battalions held on,

eventually firing off all of their ammunition.

Klenau believed that Liebertwolkwitz was occupied by 3,000 men and supported by 24 guns on a nearby hill. He knew that the rest of Lauriston's V Corps stood nearby, supporting the village's defenders. He ordered General Baumgarten's Austrian brigade to attack the village from the direction of Holzhausen, and take on the French left flank. Klenau also sent 10 to 15 guns to occupy a small knoll between Liebertwolkwitz and Holzhausen, to support the attack, and established a strong skirmish line in front of his troops.

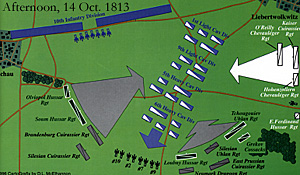

On the north edge of the University Forest stood the Wallachian-Illyrian Grenz Battalion (light infantry), which in conjunction with the Hohenzollern Chevaulegers and the

Erzherzog Ferdinand Hussars, drove back the French skirmishers on the southern slope of Liebertwolkwitz. At the same time, the Erzherzog Karl Infantry Regiment and the 3rd Battalion of the Lindenau Infantry Regiment sent detachments into the Nieder Forest, in order to hold themselves ready to attack towards Liebertwolkwitz. An Austrian horse battery positioned itself

under the protection of the grenz and hussars west of Gross-Posna. Here it opened fire, and cleared the slope south of Liebertwolkwitz of the French.

On the north edge of the University Forest stood the Wallachian-Illyrian Grenz Battalion (light infantry), which in conjunction with the Hohenzollern Chevaulegers and the

Erzherzog Ferdinand Hussars, drove back the French skirmishers on the southern slope of Liebertwolkwitz. At the same time, the Erzherzog Karl Infantry Regiment and the 3rd Battalion of the Lindenau Infantry Regiment sent detachments into the Nieder Forest, in order to hold themselves ready to attack towards Liebertwolkwitz. An Austrian horse battery positioned itself

under the protection of the grenz and hussars west of Gross-Posna. Here it opened fire, and cleared the slope south of Liebertwolkwitz of the French.

The Erzherzog Karl Infantry formed itself in two lines, the 2nd Battalion in the first line and the 1st Battalion in the second line. The regiment then began advancing towards Liebertwolkwitz. The 3rd Battalion of the Lindenau Regi ment remained as a reserve behind the left flank. Klenau then sent Splenyi's brigade and 10 squadrons of Desfours' cavalry brigade towards Gross-Posna and moved Schaffer's brigade's battery forward.

Klenau then formed two batteries, one by Gross-Posna and one on the Kolmberg hill. From these positions he could fire on the east exit from Liebertwolkwitz. The two 12-pdr batteries of the corps reserve were sent forward somewhat later to Gross-Posna.

At 11:30 a.m., the 2nd Battalion of the Erzherzog Karl advanced at the "doublierschritt," without stopping to fire, to a position 100 paces from the village of Liebertwolkwitz, and then broke into a dead run. They quickly pushed into the village. The gardens, lanes and houses of Liebertwolkwitz were heavily defended, and the French fought furiously to hold the village. The 1st Battalion was soon forced to join the battle, supporting the 2nd Battalion, as they pushed through the entire village. Only the western portion and the church court remained in the possession of the French. The situation was stabilized about 2:15 p.m.

Three times the French tried to retake the village, but the two Austrian battalions held on, eventually firing off all of their ammunition. Now the Lindenau Regiment advanced into the village. Its 3rd Battalion relieved the Austrians fighting in the eastern part of Liebertwolkwitz. The battalion commander, Hauptmann Petsch, was shot in the head during the battalion's advance, yet despite his wound he remained in command, leading his battalion to its place, and setting up its defense. Finally, however, he was obliged to leave the battle line.

The 2nd Battalion of the Lindenau Regiment, under Major Freiherr von Harnach, along with part of the 3rd Battalion, occupied the middle of the village. The 1st Battalion began a new effort to drive the French out of the western portion of the village. However, the French force in this part of the village was especially strong, and they were supported by heavy artillery fire from the Galgenberg Heights. The battalion, despite its tremendous effort, failed and was pushed back to the Wind Mill Heights south of the village. The Erzherzog Karl Regiment reorganized itself shortly later to the east of the village, where the Wurttemberg Infantry Regiment had also taken up positions.

Klenau's light cavalry of the advanced guard formed behind the Wallachian-Illyrian Grenz Battalion, in echelons to the left. Behind them was Desfours' cavalry brigade. It was formed with the famous O'Reilly Chevauleger Regiment in the first line, and Kaiser

Cuirassier Regiment in the second line. Despite the heavy French fire artillery fire, Colonel Rothkirch, upon seeing the situation of the Lindenau Regiment in Liebertwolkwitz, sent a number of Austrian batteries to the Wind Mill Heights to support the infantry.

Klenau's light cavalry of the advanced guard formed behind the Wallachian-Illyrian Grenz Battalion, in echelons to the left. Behind them was Desfours' cavalry brigade. It was formed with the famous O'Reilly Chevauleger Regiment in the first line, and Kaiser

Cuirassier Regiment in the second line. Despite the heavy French fire artillery fire, Colonel Rothkirch, upon seeing the situation of the Lindenau Regiment in Liebertwolkwitz, sent a number of Austrian batteries to the Wind Mill Heights to support the infantry.

Murat Renews the Assault

At this time, about 2:00 p.m., Murat chose to send his cavalry forward once again in a massive column. Milhaud's 6th Heavy Cavalry Division led the attack, followed by l'Heriter's 5th Heavy Cavalry Division, Subervie's 9th Light Cavalry Division and Berkheim's 1st Light Cavalry Division of the I Reserve Cavalry Corps. On the Galgenberg plateau, between the two artillery lines, Murat formed his cavalry mass. Once formed, Murat sent his forces towards Gulden-Gossa, with Pahlen's cavalry as its target.

Murat, believing the moment had come to finish the allied force,

formed the cavalry of the V Cavalry Corps

and threw them against the allied batteries.

Klenau observed the French from his vantage point, and sent Lt. Colonel Kothmayer, with the six platoons of the Hohenzollern Chevaulegers assigned to defend his headquarters, to attack the French dragoons in the flank. Rittmeister Czen of the Erzherzog Ferdinand Hussars stood with his squadron to the west of the Wind Mill Heights, guarding the Austrian artillery stationed there. He saw the critical nature of the French attack, and without awaiting orders, he led his squadron forward into the exposed French flank as the French dragoons moved past his position on the heights. Desfours' brigade, consisting of the Kaiser Cuirassier Regiment and the O'Reilly Chevauleger Regiment, also received an order from Klenau to follow the Ferdinand Hussars, and strike the left flank of Murat's cavalry.

Klenau's horse artillery, supported by a squadron of the Erzherzog Ferdinand Hussars and the Hohenzollern Chevauleger Regiment, took up a position and established a cross fire with the Prussian and Russian batteries already on the field.

Klenau's horse artillery, supported by a squadron of the Erzherzog Ferdinand Hussars and the Hohenzollern Chevauleger Regiment, took up a position and established a cross fire with the Prussian and Russian batteries already on the field.

The fire of the main Allied battery, slightly to the right of the advancing French column, was devastating. This battery consisted of the 36 guns of Prussian Horse Batteries #2, #9, and #10, and Russian Horse Battery #7. As the French assault slowed, the Olviopol and Soum Hussars and the Brandenburg Cuirassiers struck to the right of the head of Milhaud's column. They were supported by the Silesian Cuirassier Regiment.

Klenau's horse artillery, supported by a squadron

of the Erzherzog Ferdinand Hussars

and the Hohenzollern Chevauleger Regiment,

took up a position and established a cross fire

with the Prussian and Russian batteries already on the field.

The Silesian Uhlans struck the left of the French column, supported by the Loubny Hussars and Tchougouiev Uhlans. Behind them advanced the East Prussian Cuirassier Regiment and the Neumark Dragoon Regiment. The Grekov #8 Cossacks stood behind the Tchougouiev Uhlans.

The squadrons of the Ferdinand Hussars and Hohenzollern Chevaulegers supporting the Austrian horse artillery also joined in the attack, once the artillery was no longer able to fire without hitting its own cavalry.

The assault on the head and flank of the French column was more than the French cavalry could take, and they quit the battlefield. As they withdrew, the French artillery redoubled its fire, inflicting considerable losses on the allied cavalry.

On Pahlen's far left flank near MarkKleeberg, the Grodno Hussars, the Silesian Landwehr Cavalry, and the Illowaiski #12 Cossacks held off the Polish cavalry until the arrival of the Russian 3rd Cuirassier Division.

On Pahlen's far left flank near MarkKleeberg, the Grodno Hussars, the Silesian Landwehr Cavalry, and the Illowaiski #12 Cossacks held off the Polish cavalry until the arrival of the Russian 3rd Cuirassier Division.

The shattered French cavalry moved to Probstheida and through the infantry standing there. The Allied pursuit moved against that infantry, as the last phase of their pursuit. During this attack, part of the French artillery positioned on the Galgenberg Heights found its position compromised when the Lindenau Regiment had driven the French infantry completely out of Liebertwolkwitz.

The French infantry was driven back to the heights between Liebertwolkwitz and Probstheida. French artillery moved up and soon showered the Austrians with shot and shell. Klenau moved to the Wind Mill Heights, in order to join with Colonel Stein and direct the fire of the Austrian artillery. Colonel Rothkirch, at Klenau's side, was struck and killed by a cannonball.

Despite the success of his infantry, Wittgenstein stopped the advance. At this time, the English military attache, Major General Wilson, and somewhat later Colonel Latour from Schwarzenberg's headquarters, bought orders to avoid a decisive battle. Perhaps Klenau had also received an earlier verbal order. He transferred the direction of the battle to General Hohenlohe, and moved towards Pomssen.

Around 5:30 p.m., Maison's 16th Division, V Corps, began a counter-attack towards Liebertwolkwitz. Hohenlohe, the commander of the 2nd Austrian Division, left the defense to the Wurttemberg and Erzherzog Karl Infantry Regiments. The attack was so powerful, and perhaps so surprising, that the Austrians were thrown back, abandoning Liebertwolkwitz. They fell back to Gross-Posna. The Austrian artillery on the Wind Mill Heights was suddenly in danger of being taken by the French. Kapitanleutnant Smikal, with the 5th Company, Wurttemberg Infantry Regiment, held back the French attacks against the artillery. The French did not push beyond Liebertwolkwitz. The Austrians held the University Forest to Nieder Forest line with their advanced posts. The remainder of the 4th Armeeabteilung was withdrawn from the battle, and pulled back to their bivouacks for the night.

The line of Wittgenstein's advanced posts ran from the University Forest through the plateau north of Gulden-Gossa, to the sheep pens by Auenhain and on to Crostewitz in front of Wachau and Mark-Kleeberg.

The Russian light cavalry moved to a position to the right of Gulden-Gossa. Gorchakov, with his 1st Russian Corps, the Prussian reserve cavalry brigade under Roder, the Neumark Dragoon Regiment, and their horse artillery stood northwest of Stormthal. The Prussian landwehr cavalry took up a position before Crobern. Wurttemberg's 2nd Russian Corps bivouacked, with the 9th Prussian brigade, southwest of Gulden-Gossa. Klenau, who had been pushed out of Liebertwolkwitz, assumed a positionby Pombsen. Helfreich's 14th Division, the 10th, 11th, and 12th Prussian Brigades, and the 3rd Russian Cuirassier Division were by Crobern, and Raevsky's supporting Russian Grenadier Corps stood north of Espenhain. Kleist's headquarters were in Dechwitz and Wittgenstein's was in Molbis.

There is very little information on the activity of Baumgarten's detachment during 14 October. It appears that General Baumgarten and his weak forces advanced through Seifertshain, towards Holzhausen. However, he encountered a force of French infantry and about 10 guns, which hindered his march. As a result, he was unable to join the battle by Liebertwolkwitz. Instead, he was in the first line, securing the northern flank, and the line of retreat. He passed the day directing the fruitless skirmishing of the 2nd Battalion of the Kerpen Infantry Regiment. As evening fell, Baumgarten was near Naunhof, while Colonel O'Brien and his detachment moved up from Rochlitz and occupied Grimma.

The losses of the Austrians in the battle of Liebertwolkwitz were very heavy, especially for the Lindenau Regiment and the artillery. In fact, of the twelve Austrian guns lost in the battle, five were dismounted. Klenau appears to have lost about 1,000 men hors de combat, while the Silesian Cuirassiers alone lost 13 officers and 96 men. The losses of other regiments varied considerably.

The battle of Liebertwolkwitz had cost the French 500 to 600 casualties, including General Pajol and General Montmarie, who were wounded, and another 1,000 men were lost as prisoners to the allies.

The battle of Liebertwolkwitz had cost the French 500 to 600 casualties, including General Pajol and General Montmarie, who were wounded, and another 1,000 men were lost as prisoners to the allies.

Liebertwolkwitz was not a conclusive fight in any sense. It showed the superiority of Allied cavalry that day over the French, which is not a surprise, especially given that the French heavy cavalry was largely comprised of dragoons rather than cuirassiers. Murat has been criticized for wasting his troopers and horses in this action, for little result, especially in his afternoon attack, which couldn't really have accomplished much even if it had succeeded.

However, Murat did slow down the Army of Bohemia, and his action bought crucial time and space for Napoleon, who, giving up the chase of Blucher, was concentrating south to prepare a possibly decisive blow against the Army of Bohemia. This blow would land on 16 October in the Battle of Wachau, which very nearly succeeded in disrupting the Allied army. Had Napoleon fully succeeded there, Liebertwolkwitz would be seen as an important prelude to a larger victory, and perhaps Murat would have recieved great credit for pinning and holding the Army of Bohemia in place on 14 October.

In the end, however, neither side gained any critical terrain, nor did either side inflict significant casualties on the other. The battle did not appear to have any ultimate effect on the French disaster that would ultimately occur around Leipzig 16-19 October. Thus, Liebertwolkwitz will be remembered as a spectacular but inconclusive cavalry battle, reputedly the largest in history, that marked the beginning of the larger series of horrific battles known simply as Leipzig, where at last French power in Germany was shattered, and Napoleon's Grande Armee dissolved.

Comparison of Artillery in the Cavalry Battle

Order of Battle: Liebertwolkwitz

Selected Bibliography:

The books listed below were the primary sources used specifically to write the excerpted chapter on Liebertwolkwitz. For a complete bibliography used to write Napoleon at Leipzig, we refer the serious scholar and student to his book rather than attempt to select and condense the additional sources here.

Weil, M.H, Campagne de 1813, La Cavalerie des arme'es allie's, Paris, France, 1886.

Friederich, R., Geschichte des Herbstfeldzuges 1813, Vol II, Berlin, Germany.

K und K Kriegsarchiv, Befreiungskrieg 1813 und 1814, Vol V, Vienna, Austria, 1913.

About the author:

George Nafziger is a United States Naval Reserve Captain. He has authored several books on the Napoleonic Wars including: The Poles and Saxons of the Napoleonic Wars, Lutzen and Bautzen, and Napoleon at Dresden. In addition, he has done intensive research into Napoleonic orders-of-battle that he offers through a self-owned business.

Back to Editor's Note for Prelude to Leipzig

Back to Prelude to Leipzig Part I

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #4

© Copyright 1996 by Emperor's Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com