The Most Important Find Made During Bonaparte's Occupation of Egypt

The Most Important Find Made During Bonaparte's Occupation of Egypt

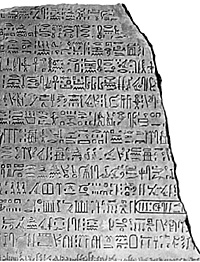

Some of history's greatest discoveries have been completely serendipitous. Such was certainly the case with the celebrated Rosetta Stone, unearthed in July of 1799. The basalt stele, or marker, was clearly the most important find made during Napoleon Bonaparte's occupation of Egypt. It derives its name from the fact that a French military engineer, Lieutenant Bouchard, and his crew dug it up while working on fortifications at Fort Julien at al-Rachid, which Europeans called Rosetta, in the Western Delta.

Egyptians who lived after the pharaonic era routinely used stone from ancient structures and monuments for their building projects, but the engineers, to their great credit, recognized that this particular fragment was unique. Its inscription was not only in hieroglyphs and demotic, an Egyptian cursive script, both unknown to modern linguists, but also in Greek. No Egyptian monument with a translation of its inscription had ever been found, and the French immediately realized that this discovery could offer the means to decipher the lost language. Under the direction of General Jacques-François Menou, who began to translate the Greek portion of the inscription, the stone was transported to the headquarters of the Institut d'Egypte.

The newspaper of the occupation force, the Courrier de l'Egypte, promptly heralded the stele as "...of great interest for the study of hieroglyphic characters, and perhaps even the key to them." The civilian scholars and scientists (known as "savants") who accompanied Napoleon's expedition to Egypt copied the inscriptions and made casts of the marker. The expedition's linguists, such as Remi Raige and Jean Joseph Marcel, began to try to decode the mysterious hieroglyphs, a challenge that would ultimately involve various scholars and take more than twenty years.

Meanwhile, the war between France and Britain continued, and when General Menou surrendered to General Sir Ralph Abercromby in 1801, the British claimed the stele and some other large antiquities as trophies of war. Negotiations for the French evacuation of Egypt were protracted and acrimonious, and one issue of contention involved ownership of the various collections and research notes that the savants had formed during the occupation. According to French accounts, the scholars threatened to destroy their work rather than surrender it to the British, a charge that British participants in the events vehemently denied.

Finally, as a compromise, the French were permitted to keep their private notebooks and small objects, while the larger antiquities, like the Rosetta Stone, which were clearly intended for French national museums, were surrendered to the British.

Just as Bonaparte had taken a corps of scholars when the French invaded Egypt, the British invasion force also brought specialists to scrutinize the French savants' collection. The two British scholars involved in the "removal" of the French discoveries were William Richard Hamilton (husband of the infamous Lady Hamilton who would become Admiral Horatio Nelson's mistress) and Edward Daniel Clarke. Clarke cheerfully observed of the savants that, "Pointers [skilled hunting dogs] would not do better for game than we have done for statues, sarcophagi, maps, manuscripts, drawings, plans, charts, botany, stuffed birds, animals, dried fishes, etc."

Clarke urged that above all the British commanders obtain the Rosetta Stone for either Cambridge University or the British Museum because "...we have better orientalists than the French, and a knowledge of eastern languages may be necessary in some degree towards the development of these inscriptions." Hamilton and Clarke, accompanied by a small escort, rowed out to a fever-stricken French ship to retrieve the stele, ensconced in the hold. The English transported the Rosetta Stone and other artifacts in 1802 and the King ordered that the marker be placed in the British Museum, where it continues to be one of the most popular exhibits today.

The Rosetta Stone significantly focused scholarly interest on linguistics and textual analysis. Although the British possessed the stele, copies of it circulated freely and many Orientalists struggled to render a completely accurate reading of the Greek and to decode the demotic and then hieroglyphic inscriptions. The task proved arduous because of numerous discrepancies in the wording of the three texts.

The two most famous scholars associated with decoding the inscription were an Englishman, Thomas Young (1773-1829), and a Frenchman, Jean François Champollion (1790-1832). Young, a linguistic genius, mathematician, and physicist deciphered the demotic part of the inscription and recognized that in the hieroglyphic text the looped rope symbol, now known as a cartouche, designated royal names. He identified the name Ptolemy, and also understood that the hieroglyphs were not purely symbolic, as long believed, but also partly alphabetic with a grammatical structure. At the age of 46, Young wrote a piece on his discoveries and on the Rosetta Stone for the 1819 edition of the Encyclopedia Britanica. His work on the ancient language advanced little, though, because like many linguists he remained wedded to the belief that hieroglyphs were still part of a symbolic system, despite his own discoveries.

Young, however, sent his work to Champollion, a 29-year-old linguistic genius who had already written on Egyptian history. Champollion also had a good command of Coptic, the modern descendant of the ancient Egyptian language. Though hesitant at first to accept the phonetic values of hieroglyphs, once he recognized it, Champollion translated the entire hieroglyphic inscription on the Rosetta Stone, working from a copy of the original.

He then cross-checked his theory and methodology by using the same techniques to read a copy of an inscription from the temple at Abu Simbel. When he translated the name Rameses and realized that his reading of the Abu Simbel text made sense, he excitedly reported to his brother, "je tiens mon affaire" (I am taking hold of the matter). He then wrote the secretary of the French Académie Royale des Inscriptions in 1822 stating that he had deciphered the language and its various rules for the forms and combinations of signs. Although his discoveries were hailed as brilliant and dramatic, many linguists remained dubious about Champollion's views of the ancient language, and some continued to hold to the opinions advanced earlier by Young. Scholarly debate about the exact nature of hieroglyphics continued throughout the 19th century. Modern scholars agree that while not quite perfect, Champollion's translation was impressive and for the most part quite correct.

Moreover, his assertion that the hieroglyphic language was not necessarily symbolic, later verified by the discovery in the 1860s of another bilingual artifact, the Decree of Canopus, opened Egypt's language and hence its written history to Egyptologists. Following the decipherment of the language, teams of epigraphers eagerly sought out and copied texts from monuments and read papyri. For the first time, Egyptologists could understand original, written sources of Egyptian history and literature, in addition to the relatively scant amounts of information presented in the Bible and Greek and Roman sources.

Thus, Egyptology moved out of the realm of antiquarian speculation and emerged as an academic discipline in which artifacts, monuments, and written records all served as evidence of Egypt's history and culture.

Napoleon in Syria, 1799

-

Napoleon in Syria: Introduction

Napoleon in Syria: From Egypt to Acre

Napoleon in Syria: Siege of Acre

Napoleon in Syria: Aftermath of Acre

Napoleon in Syria: Rosetta Stone

Napoleon in Syria: Uniforms Illustrated 1799-81 (very slow: 337K)

Napoleon in Syria: Regt Uniform Color Chart 1799-81 (very slow: 388K)

Napoleon in Syria: Campaign Maps (slow: 264K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #15

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 2000 by Napoleon LLC.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com

Order Napoleon magazine direct