Developed in 1804 for the Royal Navy largely as a means to terrorize

coastal towns, the first operational use of rockets by the British

occurred in 1806. Invented by Sir William Congreve, the Younger, by 1815

he had produced rockets which approached the hitting power and range of

most conventional artillery. Requiring fewer horses or supports than a

regular battery – the rockets were fired with the use of A-frames and

could be carried on horseback – the two rocket troops proved mobile and

relatively cheap.

Developed in 1804 for the Royal Navy largely as a means to terrorize

coastal towns, the first operational use of rockets by the British

occurred in 1806. Invented by Sir William Congreve, the Younger, by 1815

he had produced rockets which approached the hitting power and range of

most conventional artillery. Requiring fewer horses or supports than a

regular battery – the rockets were fired with the use of A-frames and

could be carried on horseback – the two rocket troops proved mobile and

relatively cheap.

Unfortunately, the extreme inaccuracy of the missiles when fired at any target smaller than the size of a large town proved to be an enormous drawback. On that account, Wellington and other army high command refused to support their employment, training and upkeep. The Duke considered them a positive menace, commenting in 1814 that he "only accepted [the rocket unit] in order to obtain the horses. I do not want to set fire to any town, and I do not know of any other use for the rockets". [Wellington's opposition being one of the reasons the rockets found employment at places such as Fort McHenry in America and Leipzig rather than in Spain, and no doubt the American national anthem would be a less inspired work without the "rocket's red glare"].

Well-trained men, competent academy educated officers, and excellent ordnance helped make the British horse gunners an effective fighting force on the battlefield. Another reason – one overlooked but vital to the good performance of any artillery unit – existed in the fact that the gunpowder used by the English during the period of 1807 to 1815 constituted the best in the world. Between the American and French Revolutions, Richard Watson, Bishop of Llandaff, applied scientific research to the manufacture of gunpowder that increased the potency of that item by almost one-half.

This in turn not only increased the striking power of the British projectiles but also their range as well. British powder greatly reduced the number of duds and misfires which plagued other artillery services during the period. More effective ammunition also increased a unit's initiative and reinforced the confidence of British gunners during combat. In an artillery starved army like the ones which fought in the Peninsula and at Waterloo, any morale or material edge that could be exploited proved to be of great assistance in combat. Confidence in its ammunition provided a vital boost to the British horse artillery.

Design Innovations

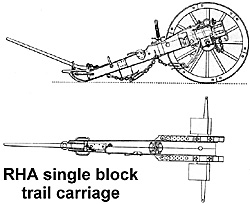

When the Duke of Richmond established the first English horse artillery

in 1793, he made it clear that this new branch of the Royal Artillery

must be quick and maneuverable. One innovation designed to help the RHA

become faster was to create a better gun trail [see diagram at right].

When the Duke of Richmond established the first English horse artillery

in 1793, he made it clear that this new branch of the Royal Artillery

must be quick and maneuverable. One innovation designed to help the RHA

become faster was to create a better gun trail [see diagram at right].

By 1793, Sir William Congreve the Elder, father of the rocket inventor, installed a new, lighter block trail design for the standard gun carriage. An unintended benefit of this design came with the advanced center of gravity for the carriage and gun barrel; this allowed a further reduction in the weight of the gun trail. This made for quicker and easier limbering and unlimbering as well as faster traversing (turning) of the piece. Overall, the block trail improved the maneuverability of the horse artillery, particularly when turning, and increased the rate and accuracy of its fire.

Tactics By Experience

Although there were government regulations issued for the firing of

guns, the maintenance of equipment, and for the proper care of the

troop's mules and horses, no official tactical doctrine existed for

combat. This led to the individual artillery commanders developing

procedures of their own based on actual combat experience and real field

service. While some commanders did perform better than others, uniformly

the horse artillerists proved outstanding in coming up with the best

ways to fight their guns. For the most part educated at university or at

Woolwich, the young captains and lieutenants, along with the many

ranking NCOs who trained at the artillery academy, formed a

knowledgeable and dedicated group of professionals. Their skills were

fine tuned and perfected in the crucible of combat, and they never

lacked the opportunity since their numbers were small and the need for

their services great. Often fighting under the very eye of Wellington,

the RHA fostered the initiative and independence essential for meeting

the demanding level of performance expected by the future Duke.

Although there were government regulations issued for the firing of

guns, the maintenance of equipment, and for the proper care of the

troop's mules and horses, no official tactical doctrine existed for

combat. This led to the individual artillery commanders developing

procedures of their own based on actual combat experience and real field

service. While some commanders did perform better than others, uniformly

the horse artillerists proved outstanding in coming up with the best

ways to fight their guns. For the most part educated at university or at

Woolwich, the young captains and lieutenants, along with the many

ranking NCOs who trained at the artillery academy, formed a

knowledgeable and dedicated group of professionals. Their skills were

fine tuned and perfected in the crucible of combat, and they never

lacked the opportunity since their numbers were small and the need for

their services great. Often fighting under the very eye of Wellington,

the RHA fostered the initiative and independence essential for meeting

the demanding level of performance expected by the future Duke.

True to their mandate for speed, the horse artillerists always galloped into action. RHA Troops would normally be broken down for battle into three "divisions" of two guns, each alternating fire. A gun line would be staggered in order to reduce the damage from enemy flanking fire.

The limber drivers would pile ammunition close to the individual guns, while the follow-up ammunition caissons, one per battery and one extra per "division", would park 50 and 100 yards, respectively, from the firing line. The rest of the troop vehicles would be positioned a further 100 yards to the rear. To lessen the danger of an ammunition explosion, only one wagon at a time would move forward to the guns to distribute needed shot and shell. Once emptied, a wagon would be replaced as it retired.

Whenever the full troop, or any part of it, came into action, the

officers, senior sergeants and troop surgeons remained mounted in order

to quickly intervene if necessary. As the action continued, the officers

would constantly be on the look-out for better positions to post their

guns. The preferred site for artillery was always just behind a gentle

rise in the ground with little or no "dead ground" to the gun's front.

Depending on the circumstances, fire was controlled, although a

well-trained gun crew might get off an average of two roundshots (ball)

per minute, keeping up that rate of fire – depending on the heat and

casualties – for about forty minutes.

Whenever the full troop, or any part of it, came into action, the

officers, senior sergeants and troop surgeons remained mounted in order

to quickly intervene if necessary. As the action continued, the officers

would constantly be on the look-out for better positions to post their

guns. The preferred site for artillery was always just behind a gentle

rise in the ground with little or no "dead ground" to the gun's front.

Depending on the circumstances, fire was controlled, although a

well-trained gun crew might get off an average of two roundshots (ball)

per minute, keeping up that rate of fire – depending on the heat and

casualties – for about forty minutes.

The ammunition relied upon most by the horse artillery (and for all artillery of this era) was roundshot (solid iron balls). With a maximum range of about 1200 yards for a 6-pounder and 1700 yards for a 9-pounder, roundshot worked best at slightly shorter ranges (700-1000 yards), where it could be fired with a relatively flat trajectory. Known as ricochet fire, a solid ball propelled in this manner would bounce and skid after its first impact, causing fearful damage to anything in its path [unlike Hollywood depictions, such shots did not "explode" but often did kick up a great deal of dirt and debris].

Common shell [which did explode] represents the majority of ammunition fired by howitzers. The trick to this higher trajectory mode of firing came when artillerists attempted to measure and cut the fuses, a job which required considerable skill and a fair amount of good luck to get the explosion to occur directly over a target. Common shell had "effective" ranges against stationary targets out to about 700 to 1200 yards.

Spherical case shell (Shrapnel) proved deadliest at 200 yards, but a 6-pounder might routinely employ such shells against troops at 400 yards, while a 9-pounder might use Shrapnel out to about 600 yards. Against artillery (counter-battery) and in certain special situations, Shrapnel could be employed at longer ranges up to 700 to 1500 yards. Both common shell and shrapnel could be fired over the heads of friendly troops at long ranges to reach opponents sheltering behind obstacles or occupying structures. Although such "indirect fire" had a much lower rate of accuracy, it could have a great deal of effect upon its victims. Furthermore, howitzer fire proved highly effective as an incendiary device.

The canister employed by the regular guns worked best at short range. A 6-pounder had a range limit of 400 yards and a 9-pounder could throw canister out to 600 yards. Except at the shorter ranges, where two rounds might be fired at once in defense of the battery, canister tended to dive into the ground or pass through gaps or over the heads of its target. Only at shorter ranges did it prove devastating.

The RHA in Battle

Perhaps the most famous exploit of the RHA came at Fuentes de Onoro on 5 May, 1811.

Resisting a turning movement of Wellington's right flank by Marshal Masséna, the English Light and 7th Infantry Divisions stubbornly fought to buy time for the rest of Wellington's force to reach its fallback position in and around the village of Fuentes de Oñoro. The foot soldiers received support from the 14th Light Dragoons and Bull's (howitzer) Troop I of Royal Horse Artillery. Masses of French horsemen pursued the retiring redcoats. The infantry formed into marching squares, while the Light Dragoons made repeated counter-charges supported by blasts from Bull's battery.

As the action neared the village, French cavalry squadrons broke through the British rearguards and made straight for Lieutenant William Ramsay's two-gun division, cutting it off from friendly support. Ramsay had just limbered his guns after firing yet another salvo at the pursuing enemy cavalry when he noticed other French troopers coming at him from the flank. Soon encased within a ring of saber-wielding and pistol shooting Frenchmen, Ramsay ordered his men to return fire with their own side arms.

After a few such return volleys, the English officer, undismayed by his desperate situation, as Oman describes: "put his guns to the gallop, and charging himself in front of them with the mounted gunners cut his way through the French...." The efforts of two friendly squadrons of British cavalry were of great help to Ramsay, and his command broke though the enemy cordon. Ramsay's dash to freedom was not only a heroic act, but also served to distract the French cavalry, thus gaining more time for the British infantry to reach their new defensive positions. Tragically, Ramsay would be killed four years later at Waterloo.

The 2nd Rocket Troop, Royal Horse Artillery, formed in 1813 and served with the Swedish Army (under former French Marshal Bernadotte) in the titanic struggle that same year in Saxony. Commanded by Richard Bogue, a noted innovator in the tactical use of rockets, the battery arrived late on 18 October upon the great battle of Leipzig. Bogue positioned his battery and raced to join the fight with his men and the 12-pound rockets they carried on each horse. He faced the village of Paunsdorf, west of the city of Leipzig, and commenced to support a Prussian unit against the French in the hamlet. Stung by a rain of missiles coming from Bogue's Troop, the rockets inflicting as much terror as actual harm, the defending French battalion soon retreated from its position in Paunsdorf.

Desiring to obtain a better view of the situation, Captain Bogue mounted a horse, and soon observed a part of the French force, in square, starting to surrender, while the remainder continued their withdrawal. Bogue immediately called for his dragoon escort to follow him and arrest the flight of that part of the enemy infantry which continued to retire. Spurring his horse after the enemy, Bogue closed in, then some of the retiring Frenchmen turned about and delivered a volley at the approaching horsemen. Bogue was killed instantly, a musket ball penetrating to the back of his head. He left behind a young wife and two small children. He would be the highest ranking officer in the rocket service to die during the Napoleonic Wars.

Augustus Simon Frazer served as an artilleryman in the campaigns of 1793-1794; transferred to the horse artillery in 1795; rose to command all of Wellington's horse artillery in 1813; and fought with great skill and energy at Waterloo.

Lt.-Colonel Frazer's strategy to parcel out a modest amount of horse artillery as close support for the infantry, while keeping a small reserve, successfully countered the numerically superior French batteries at Waterloo. During the fight he consistently managed to place his uncommitted guns – troop by troop – to reinforce weak spots just when they were needed. He ordered at least twelve tactical battlefield moves for some or all of the troops under his control. Frazer's sagacious and quick handling of the RHA at Waterloo proved one of the decisive factors in enabling Wellington to hang on long enough for Blücher's Prussians to enter the battle and turn the tide against Napoleon.

Legacy of Valor

Between 1793 and 1815, units of the Royal Horse Artillery fought in nineteen major battles and scores of minor engagements. Many times the RHA found itself pushed to the forefront of the battle, in the most daring way, and each time the RHA proved its mettle and paid the cost. Commanders such as Majors Ramsay, Major Beane, and Captain Bogue were killed in action; many others were wounded.

As a final testament to the professional excellence of the British horse artillery, one statistic speaks volumes: Not a single RHA artillery gun was ever captured by the enemy during this entire period of warfare.

About the Author:

Arnold Blumberg is a lawyer for the state of Maryland. A contributor to the Journal of the War of 1812, he is currently working on a book about the British horse artillery during the Napoleonic era. A version of this article first appeared in the March 1997 edition of Military and Naval History Journal.

Bibliography:

Bowden, Scott, Armies at Waterloo, Arlington: Empire Games Press, 1983.

Congreve, Sir William, Details of the Rocket System, London: Hargrove

Printers, 1814.

Depuy, Trevor N., The Military Life of Frederick the Great of Prussia,

New York: Franklin Watts, 1969.

Frazer, Sir Augustus S., (edited by Edward Sabine), Letters of Colonel

Sir Augustus Simon Frazer, London: Longman, Brown, Green Longmans, and

Robert Publishers, 1859.

Glover, Richard D., Peninsular Preparations: The Reform of the British

Army, 1795-1809, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1963.

Haythornthwaite, Philip J., The Armies of Wellington, London: Arms and

Armour Press, 1994.

Haythornthwaite, Philip J., Wellington's Specialist Troops, London:

Osprey Publishing, 1988.

Hughes, P.B., Open Fire: Artillery Tactics From Marlborough to

Wellington, Sussex: Anthony Bird Publications, 1983.

Luvass, Jay (editor), Frederick the Great on the Art of War, New York:

The Free Press, 1966.

Mercer, Cavalié, Journal of the Waterloo Campaign, London: Greenhill

Books, 1985.

Nosworthy, Brent, The Anatomy of Victory: Battle Tactics 1689-1763, New

York: Hippocrene Books, 1990.

Oman, Charles, A History of the Peninsular War (seven volumes), London:

Greenhill Books, 1996.

Park, S.J., and Nafziger, George, The British Military: Its System and

Organization, 1808-1815, Cambridge: Rafm Company, 1983.

Rothenberg, Gunther, The Art of War in the Age of Napoleon, Bloomington:

Indiana University Press, 1980.

Siborne, Captain W., History of the Waterloo Campaign, London: Greenhill

Books, 1995.

Wise, Terence, Artillery Equipments of the Napoleonic Wars, London:

Osprey Publishing, 1979.

More British Royal Horse Artillery

-

Introduction

Early Organization and Evolution

Battlefield Innovations and Advantages

At Waterloo, 1815

Organization at Waterloo

Large Map of Artillery Positions at Waterloo (slow: 180K)

RHA Uniform Plates: 1793 and 1815 (slow: 144K)

RHA Uniform Plates: Mercer Troop G at Waterloo (73K)

Cover Illustration: RHA at Fuentes de Onoro, 1811 (slow: 211K)

Back to Table of Contents -- Napoleon #12

Back to Napoleon List of Issues

Back to MagWeb Master Magazine List

© Copyright 1998 by Emperor's Press.

This article appears in MagWeb (Magazine Web) on the Internet World Wide Web.

The full text and graphics from other military history magazines and gaming magazines are available at http://www.magweb.com